Trademarks (and service marks) serve to identify a particular source of a product or service. The purpose of trademark law is tied to that source-identifying function. Trademark rights arise through use. Registration is optional. What matters most in terms of a brand eligibility for trademark protection is its strength or distinctiveness, together with any any prior conflicting uses of identical or similar brands already taken by others.

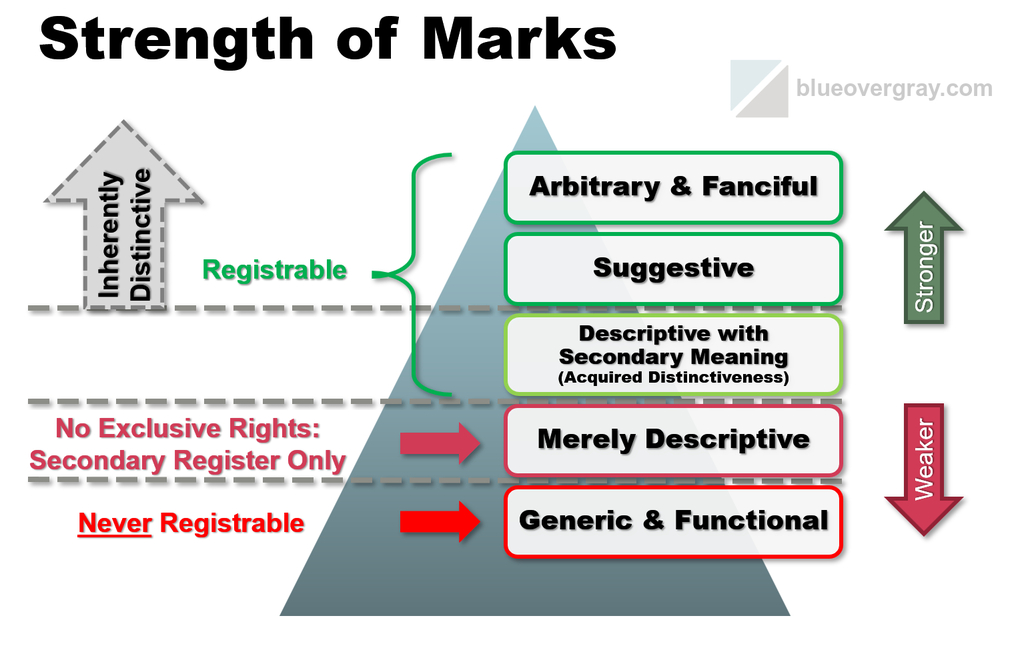

Generally, a brand can be protected under trademark law if it is distinctive enough to serve such a source-identifying function—and it is actually used for that purpose. There is a continuum of kinds of marks that separates distinctive ones capable of exclusive rights and ones that are not distinctive and do not entitle the user to any exclusive rights. The possibility of exclusive trademark rights depends first of all upon selecting a mark that is distinctive enough. Doing that properly requires some understanding of the strength continuum of mark distinctiveness.

Brands and marks are categorized along the following range or continuum of increasing conceptual distinctiveness: (1) generic, (2) descriptive, (3) suggestive, (4) arbitrary, or (5) fanciful. A mark that is fanciful, arbitrary, or suggestive is considered to be inherently distinctive and automatically is eligible for federal trademark protection—long ago these were referred to as technical trademarks. While these categories are well-established now, there may be dispute as to where any given mark falls on this continuum. Changes in how a mark is used over time can also complicate these determinations.

A fanciful mark is a non-dictionary word concocted by the user. These are sometimes referred to a coined marks. Some examples are EXXON® for petroleum and petroleum products, and many pharmaceutical brands that are completely made-up names.

An arbitrary mark is a known word used in an unexpected or uncommon way. An example is APPLE® for computers.

A suggestive mark is one for which a consumer must use imagination or any type of multistage reasoning to understand the mark’s significance. A suggestive mark does not directly describe features of the product or service but instead suggests them. Example are ESKIMO PIE® for frozen confections and KITCHENAID® for small household devices and utensils.

Descriptive terms define qualities or characteristics of a product in a straightforward way that requires no exercise of the imagination to be understood. Merely descriptive terms are not entitled to trademark protection. Only marks that have acquired secondary meaning through extensive and substantially exclusive use over a sufficient period of time attain acquired distinctiveness to potentially be protectable as trademarks. Simply being the first to use a descriptive term is not enough. An example of a merely descriptive term is “cotton” for t-shirts made at least partly from cotton, or the term “large” to describe the size of the t-shirt. An example of a descriptive mark that has acquired secondary meaning in the USA is AMERICAN AIRLINES® for air transport of passengers and freight.

Generic terms are what the public understands to be the common names of associated products or services. Another way of stating this definition is that a generic term denotes a category (genus) of goods/services of which a particular brand is one species. A generic term does not signal any particular source and can never serve as a protectable mark under trademark law. Usage and advertising can never make a generic term protectable. Some examples of generic terms are “breakfast cereal” or “television” for those same goods. Some terms that were at one time protectable can also become generic, such as “escalator” for moving walkways.

The distinctiveness of a mark depends on how it is being used. The same mark might fall in different distinctiveness categories in different contexts. For example, the mark APPLE® may be arbitrary when used to identify a source of computers but “apple” is generic when applied to the fruit widely known by that name.

When it comes to trade dress, a form of trademark protection, functional aspects are not protectable. In this sense, functional aspects of things themselves are treated like generic terms—alone they are ineligible for trademark protections. An example of a functional feature is the shape of a key that allows it to fit into a corresponding lock.

A “trade name” is somewhat different from a trademark. A trade name is the formal legal name of a corporate entity, or its formal assumed name (DBA). For instance, “Acme, Inc.” a hypothetical corporation registered in a particular U.S. state, is a trade name. While it is possible that such a company sells ACME or ACME, INC. brand widgets, it might instead sell EXAMPLE brand widgets. Trade name and trademark usage may not be the same. There tend to be different (and less stringent) legal standards applied to securing trade names than to securing trademark rights. A common mistake is to believe that forming a corporation or registering an assumed name with a state—alone—creates trademark rights, when trademark rights in the U.S. require both use of the mark (as a mark) and a sufficient level of distinctiveness.

Also keep in mind that registering an Internet domain name does not by itself establish any trademark rights. While the availability of a suitable domain name is often an important consideration when selecting and adopting a brand, domains can be registered without regard for the use and distinctiveness requirements that apply to trademarks. Moreover, using a domain URL merely as an Internet address is not the same as trademark use as a source identifier.

When selecting a mark, it is common for businesses to gravitate toward conceptually weak marks as brands because they “sell themselves” and are immediately recognized by consumers for what those marks represent. So there is less investment required at the outset to establish consumer recognition of the brand. But some things are too weak to even function as marks and will not be protectable at all. Selecting a merely descriptive term as a brand will not allow for any exclusive rights unless and until secondary meaning (acquired distinctiveness) is achieved over a significant period of time. But even descriptive marks that have acquired distinctiveness are still subject to descriptive fair use defenses that limit the scope of exclusivity. And a generic term is never entitled to exclusivity, regardless of usage or advertising effort. Anyone who wants to have exclusive rights in a brand needs to select a mark that is distinctive enough to merit trademark protection.

Also, trademark strength can actually be assessed in different ways, to refer to either protectability or scope of exclusivity. There is inherent or conceptual strength, which categorizes how a mark naturally is or is not capable of serving as a source identifier. That is about protectability, and whether there can be any exclusive rights for a given mark when used with particular goods/services. But there is also commercial or marketplace strength, which refers to the level of exclusive use as a brand by a particular entity (secondary meaning). That is generally about the scope of exclusive rights. For instance, a suggestive mark may be conceptually/inherently strong (distinctive) enough to be protectable, but if there are many other entities using similar marks due to similar suggestive connotations then the commercial strength and degree (scope) of exclusivity in the coexisting marks is lessened. Likewise, a fanciful/coined term may be conceptually strong as a mark but may still be commercially weak if its usage has been limited in duration and there has been negligible advertising.

Lastly, recognize as well that many marks are already taken by others, which limits the universe of marks freely available for another business’ use at the time of adoption. It is not unusual for a first-choice mark (and second-choice…) to be already taken. Conducting a legal clearance when adopting a brand is recommended to avoid conflicts with someone else’s preexisting trademark rights.

Austen Zuege is an attorney at law and registered U.S. patent attorney in Minneapolis whose practice encompasses patents, trademarks, copyrights, domain name cybersquatting, IP agreements and licensing, freedom-to-operate studies, client counseling, and IP litigation. If you have patent, trademark, or other IP issues, he can help.