By Austen Zuege

Introduction

The following is a guide to trademark registration filings in the United States of America by foreign applicants. Discussed are original application filings in the USA (without any claim of foreign priority), Paris Convention priority filings, and Madrid Protocol extensions to the USA. This guide is intended primarily for the benefit of trademark attorneys in other countries seeking to understand the available options and legal requirements for U.S. trademark registration with the U.S. Patent & Trademark Office (USPTO). It encompasses recommended practices, common mistakes, and common questions, with emphasis on areas of U.S. trademark law and practice that may differ from those of other countries.

Table of Contents

- Overview of Trademark Law and Practice in the USA

- Types of Marks Registrable

- Conflicting Marks

- Types of U.S. Federal Registrations: Two Different Registers

- Filing Bases

- Identifications of Goods and/or Services

- Specimens

- Signatures

- Maintenance and Renewals

- Challenging Registration

- Misleading Notices and Scams

Overview of Trademark Law and Practice in the USA

Background of Federal and State Trademark and Unfair Competition Laws

In the United States, legal rights in trademarks (and service marks) are generally based on use. The traditional purpose of trademark law, as a part of the law of unfair competition, is preventing consumer confusion, which occurs through use of a mark that identifies a single source of particular goods and/or services. As such, trademark rights are tied to underlying customer “goodwill” and a mark or registration cannot be assigned apart from that underlying “goodwill” (without risking loss of trademark rights).

That fact that U.S. trademark rights are tied to use is very different from the law in many other countries. It is not possible to reserve a mark in the U.S. through registration merely to block others from using it. Accordingly, U.S. federal practice often prohibits overly broad identifications of goods and services that extend beyond actual or planned use. However, applicants able to make a foreign priority claim have a unique opportunity to obtain a U.S. federal registration without having yet used the registered mark in the USA. Yet applicants claiming foreign priority must still have a good faith intention to use the mark in the USA or in international commerce between the USA and a foreign country.

U.S. federal trademark law is provided by the Lanham Act (15 U.S.C. § 1051et seq.), which also includes domain name anti-cybersquatting (ACPA) and false or misleading advertising provisions. A federal registration is valid across all U.S. states, territories, districts, and possessions. Both registered and unregistered (“common law”) marks can be enforced in federal courts. Though a registration provides numerous enforcement and protection benefits to the owner as compared to mere common law rights.

There is no explicit constitutional authorization for federal trademark protection in the USA. Instead, constitutional authority for federal trademark protections under the Lanham Act (15 U.S.C. § 1051et seq.) is derived from the Commerce Clause (Art. 1, § 8, cl. 3). This is why U.S. federal trademarks have a use in commerce requirement (See TMEP § 901 et seq.). The Commerce Clause pertains to foreign and interstate commerce, so trademark uses unconnected to interstate/foreign (or tribal) commerce fall to state law.

There are also state trademark and unfair competition laws. These laws and their requirements for registration vary by state. Registration in individual state(s) is possible but is generally much less desirable than federal registration. State trademark laws have no provisions for foreign priority. Enforcement of registered and unregistered marks is possible in individual state court(s), but, as a practical matter, this may be largely redundant with federal trademark enforcement. Most trademark litigation in the U.S. happens in federal courts. And federal courts generally allow related state law claims to be brought along with related federal trademark claims under supplemental jurisdiction.

Applicable Federal Trademark Statutes, Regulations, and USPTO Procedures

U.S. federal trademark laws are part of the Lanham Act, which is the statutory authority that governs federal trademark registration and enforcement. Although it can be confusing, it is common to refer to sections of the Lanham Act that were subsequently codified in Title 15 of the U.S. Code. For example:

- § 1 of the Lanham Act = 15 U.S.C. § 1051

- § 2(f) of the Lanham Act = 15 U.S.C. § 1052(f)

- § 43(a) of the Lanham Act = 15 U.S.C. § 1125(a)

- § 44 of the Lanham Act = 15 U.S.C. § 1126

- § 66 of the Lanham Act = 15 U.S.C. § 1141f

See complete correspondence list of Lanham Act and U.S. Code sections here

Federal regulations (rules) governing trademark registration at the U.S. Patent & Trademark Office (USPTO) are found in 37 C.F.R. Chapter I, Parts 2, 3, 6, 7, and 11. More detailed guidance about USPTO registration procedures are found in the Trademark Manual of Examining Procedure (TMEP). Additionally, procedures of the Trademark Trial & Appeal Board (TTAB), an administrative court within the U.S. Trademark Office, are found in the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board Manual of Procedure (TBMP).

Foreign Applicants Must Have U.S. Counsel

The USPTO requires all foreign applicants to be represented by an attorney licensed by a U.S. state, territory, etc. (with some limited exceptions for recognized Canadian practitioners). This U.S. counsel requirement applies even for Madrid Protocol extensions. Any U.S.-licensed counsel electronically filing papers for trademark applications must also complete identity verification with the USPTO.

Types of Marks Registrable

Things That Can Serve as Registrable Marks

A registrable mark in the U.S. can be nearly anything that serves a source-identifying function. Common types of registrable marks are:

- Word mark (standard characters; need not be in English language; includes compound marks)

- Design mark (logo, sometimes called a “device” mark in other countries)

- Composite mark (both words and a design and/or stylized font and/or color)

When a mark consists of one or more words, without any claim to and font, color, or the graphical appearance of the mark, it is referred to by the USPTO as a (pure) word mark in “standard characters.” In terms of registration, such a mark is broader than one that is limited to a particular visual representation of those same words. Slogans and other unitary phrases that create a distinct commercial impression (as a whole) and are are used in a trademark sense to serve a source-identifying function may be registrable as word marks.

Compound marks are those that include two or more distinct words (or words and syllables) that are represented as one word. These include portmanteau terms, telescoped words (combining two or more words that share letters), and compound words (formed with a hyphen or other punctuation). A compound marks would be considered a word mark if it contains no non-literal design element or graphical stylization.

Composite marks are sometimes informally referred to by the words (or literal elements) of the mark and a “plus design” indication, such as “EXAMPLE MARK + design”, to clarify that there are non-literal graphical elements present. Though the term “composite” is used in many different (and sometimes vague) ways, and that term is also used to refer to marks that are simply made up of multiple words (like a unitary phrase).

Less common (non-traditional) types of registrable marks include:

- Trade dress (for example, nonfunctional packaging shape plus colors, or nonfunctional product configuration)

- Certification mark

- Collective mark (indicating membership in a group)

- Color, sound, scent, etc. (but these types of non-traditional marks are often more difficult to register)

Strength of Marks: Sufficient Distinctiveness Required

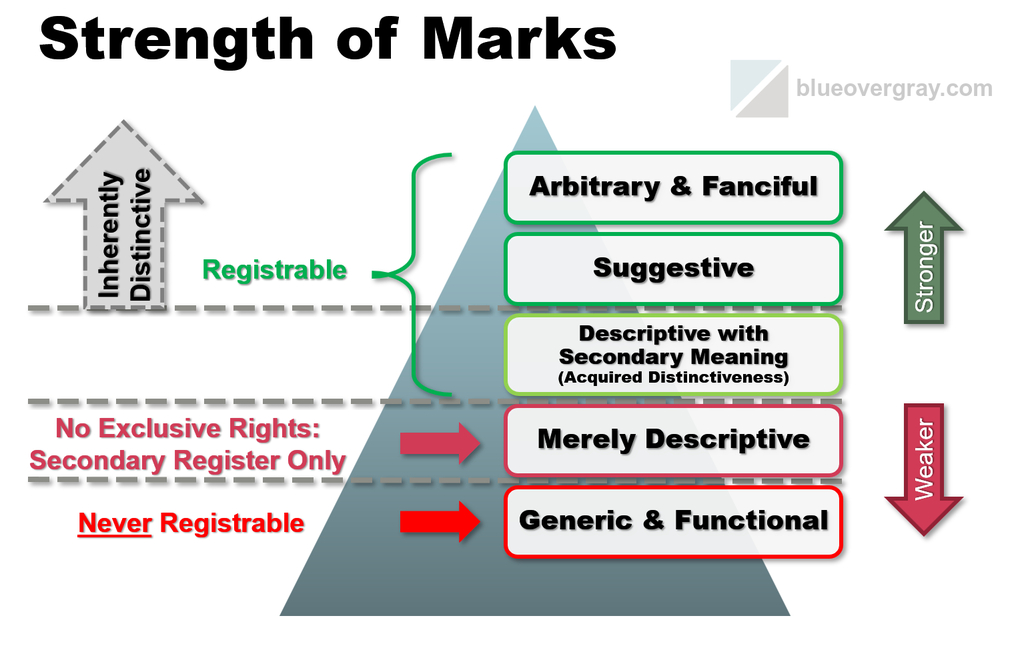

Apart from potential conflicts with existing marks, a brand is generally eligible to be protected under U.S. trademark law if it is distinctive enough to serve such a source-identifying function—and it is actually used or intended to be used for that purpose. There is a continuum of conceptual or inherent strength that separates distinctive marks capable of registration from ones that are not distinctive and may not be registrable on the Principle Register at a given time, or at all. The possibility of registering a mark to establish exclusive rights in that mark depends first of all upon selecting a mark that is distinctive enough on this continuum.

Brands and marks are categorized along a range or continuum of increasing conceptual distinctiveness: (1) generic, (2) descriptive, (3) suggestive, (4) arbitrary, or (5) fanciful. While these categories are well-established, there may be dispute as to where any given mark falls on this continuum for use with given goods/services. Changes in how a mark is used over time can also complicate these determinations. A mark that is fanciful (coined), arbitrary, or suggestive is considered to be inherently distinctive and is automatically eligible for federal trademark protection by the first user.

A fanciful mark is a non-dictionary word invented by the user. These are sometimes referred to a coined marks. Some examples are EXXON® for petroleum and petroleum products, and many pharmaceutical brands that are completely made-up names.

An arbitrary mark is a known word used in an unexpected or uncommon way. An example is APPLE® for computers.

A suggestive mark is one for which a consumer must use imagination or any type of multistage reasoning to understand the mark’s significance. A suggestive mark does not directly describe features of the product or service but instead suggests them. Example are ESKIMO PIE® for frozen confections and GOOGLE® for the provision of Internet search engines.

Descriptive terms define qualities or characteristics of a product in a straightforward way that requires no exercise of the imagination to be understood. Merely descriptive terms are not entitled to trademark protection. Only marks that have acquired secondary meaning over a sufficient period of time attain acquired distinctiveness to potentially be protectable as trademarks. At the USPTO, substantially exclusive and continuous use of a mark in commerce for a least the previous five years may establish secondary meaning and acquired distinctiveness for registrability, but shorter periods of use will not suffice. Simply being the first to use a descriptive term is not enough. An example of a merely descriptive term is “cotton” for t-shirts made at least partly from cotton. An example of a descriptive mark that has acquired secondary meaning in the USA over a long period of time is AMERICAN AIRLINES® for air transport of passengers and freight.

Generic terms are what the public perceives to be the common names of associated products or services. Another way of stating this definition is that a generic term denotes a class or category (genus) of goods/services of which a particular brand is one species. A generic term does not signal any particular source and can never serve as a protectable mark under trademark law. No amount of usage and advertising can ever make a generic term protectable. Some examples of generic terms are “breakfast cereal” or “television” for those same goods. Some terms that were at one time protectable can also become generic, such as “escalator” for moving walkways/stairs.

The distinctiveness of a mark depends on how it is being used. The same mark might fall in different distinctiveness categories in different contexts. For example, the mark APPLE® may be arbitrary when used to identify a source of computers but “apple” is generic when applied to the fruit widely known by that name.

When it comes to trade dress, a form of trademark protection, functional aspects are not protectable. An example of a functional product feature is the shape of a key blank that allows it to fit into a corresponding lock. In general, the three-dimensional (3D) shape of products themselves are very often functional and ineligible to trade dress protection—consider design patent protection instead. In contrast, non-functional aspects of product packaging and the like are more likely to be eligible for trade dress protection if those aspects serve a significant reputation-related source-identifying role.

Disclaimers

The USPTO may require the applicant disclaim an unregistrable component of a mark that is otherwise registrable. This is most common for composite and compound marks that incorporate generic and/or merely descriptive word(s). For example, to register the compound word mark EXAMPLE COMPUTERS for computers, a disclaimer of the generic word “computers” would typically be required. As another example, to register the composite mark COMPUTER + design (with a graphical logo incorporating the word “computer”) for computers, a disclaimer of the generic word “computer” would typically be required.

An applicant may also voluntarily disclaim a component of an applied-for mark. However, it is not required to voluntarily disclaim anything at the time a new trademark application is filed. More commonly, an applicant will instead await examination and any determination by the examiner that disclaimer(s) are required. Though applicants seeking to register a mark that includes an arguably generic or merely descriptive component should be aware that a disclaimer might eventually be required to obtain a U.S. registration.

The significance of a disclaimer in a trademark registration is that it limits the scope of exclusive rights conveyed by the registration. Disclaimers provide some notice to the public about the limits of the exclusive rights evidenced by a registration. However, by statute, a disclaimer does not “prejudice or affect” any existing or later-arising common law rights, or the ability to register the mark without a disclaimer via a later application if the disclaimed matter acquires distinctiveness (secondary meaning).

Conflicting Marks

Likelihood of Confusion Standard

The USPTO conducts a search for conflicting marks as part of the official examination of each new trademark application and may issue a likelihood of confusion refusal (under § 2(d)). However, only prior registered marks are usually considered during initial examination. But unregistered known marks might be used as a basis for refusal in some circumstances.

If a USPTO examining attorney concludes that a conflict exists between the applicant’s mark and a prior mark, registration of the applied-for mark will be refused on the ground of a “likelihood of confusion”, which is assessed based on what are called the du Pont factors. These same DuPont factors can also be used in deciding oppositions to applications and attempts to cancel an existing registration based on prior use of a mark.

Two DuPont factors are always considered by the USPTO:

- similarity or dissimilarity of the marks in their entireties as to appearance, sound, connotation, and commercial impression

- relatedness of the goods or services as described in the application and prior application(s)/registration(s)

Four additional DuPont factors might also be considered, though there may not be any evidence available to allow consideration of these other factors in the context of examination of a new application:

- similarity or dissimilarity of established, likely-to-continue trade channels (that is, actual sales methods used)

- conditions under which and buyers to whom sales are made (for instance, “impulse” vs. careful, sophisticated purchasing)

- number and nature of similar marks in use on similar goods or services

- existence of a valid consent agreement between the applicant and the owner of the previously registered mark

The six factors listed above are actually a condensed list of the ones that are most commonly relevant in the examination of new applications. The DuPont court decision actually set forth a total of thirteen factors, but the other unnamed factors are somewhat redundant and are rarely of significance.

The weight given to any of these individual factors can vary. There is no precise mathematical formula for how they are applied to reach a conclusion as to registrability. Though the comparison always involves the specific mark and the specific goods or services identified in the application or registration in question.

Actual uses of the mark in the marketplace that are not identified in the application or registration at hand are generally irrelevant for registration purposes—the USPTO only decides what can or cannot be registered. Questions about infringement are dealt with by courts instead. There are slightly different formulations of the likelihood of confusion factors applied in courts, which will depend on the particular “circuit” the court is located in that handles a given lawsuit.

But under the any formulation of likelihood of confusion factors, the overall analysis is similar. The marks do not have to be identical. Similarly, the respective goods/services do not have to be identical. It is sufficient that those things are related in such a manner that an appreciable number of ordinary purchasers are likely to assume—mistakenly—that they originate from a common source.

The USPTO provides some useful hypothetical examples of likelihood of confusion comparisons as they are normally applied during examination of a new trademark application.

One difference between treatment of likelihood of confusion in the USA and trademark examination procedures in other countries is in the role of the classification system. In the USA, the classification of goods/services is not controlling when considering relatedness. Instead, it is the likelihood of consumer confusion that controls, regardless of whether the classification of goods/services is the same or different. This means that there may be a likelihood of confusion that bars registration even if the goods/services are in different international classes. Common examples are when similar marks are used for goods and for retail services involving those goods, or for downloadable software goods and use of non-downloadable online software. Or there may not be a likelihood of confusion even if the goods/services are in the same international class.

Other Possible Grounds for Refusal

There are additional grounds for refusal other than a likelihood of confusion. These include falsely suggesting a connection with persons, living or dead, institutions, beliefs, or national symbols, being deceptive, being merely descriptive or deceptively misdescriptive, etc. Though these other potential grounds for refusal are less common that likelihood of confusion refusals.

Pre-Filing Searches

The USPTO does not require applicants to make a pre-filing search, but conducting such a search is still a best practice. Doing so can help:

- identify the existence of any prior registration(s) or application(s) that might lead to a refusal of registration

- identify potential infringement risks

- encourage earlier adoption of a different registrable and non-infringing mark if a conflict is found (the cost and burden to switch marks or re-brand increases with time)

A trademark search can be performed an many different levels of completeness and thoroughness. In other words, the scope of a trademark search can vary. There are two primary types of pre-filing searches to consider:

- Knockout/preliminary search – limited in scope (e.g., prior federal registrations and applications only); and

- Comprehensive search – broader in scope; ideally seeks to identify potentially conflicting prior unregistered uses, state registrations, domain name registrations, and potential foreign priority claims too

However, any search results require legal analysis to be worthwhile. That is to say that conducting a search and obtaining a list of search results is merely the first step in a process that further requires a likelihood of confusion legal analysis that compares any prior marks against the proposed mark in light of the du Pont factors—just as will be performed by the USPTO during examination.

Types of U.S. Federal Registrations: Two Different Registers

There are actually two different U.S. federal trademark registers, with different requirements and different benefits: the Principal Register and the Supplemental Register. Registration on the Principal Register secures rights throughout all U.S. states plus all U.S. territories and possessions. Registration on the Principal Register is always preferable and pursuit of this type of registration is normally presumed. Though there are situations where pursuing a registration on the Supplemental Register may have certain strategic benefits.

Selecting either the Principal or Supplement Register in a new trademark application is a requirement that establishes the “type” of application. However, in some circumstances, an application for the Principal Register can be amended after filing to instead pursue registration on the Supplemental Register.

Principal Register

Registration on the Principal Register is the most desirable type of federal registration. It is the only register that provides evidence of exclusive rights in a mark. Seeking and obtaining a registration on the Principal Register provides the most benefits to the applicant/registrant, including:

- Legal presumption of validity, ownership, and exclusive right to use the mark with the identified goods/services across the entire USA (§§ 7(b) and 33(a))

- Provides constructive notice to others of claim of ownership (§ 22)

- Can be used to block importation of goods bearing infringing mark into USA (§ 42 and 19 U.S.C. § 1526)

- Facilitates domain name (cybersquatting) actions (UDRP/URS/ACPA) and private marketplace exclusions (e.g., Amazon Brand Registry)

- May eventually establish incontestability (§§ 15 and 33(b)) to limit grounds for cancellation in court

- Enables use of ® symbol (§ 29)

- Mark listed in searchable records and can be considered by USPTO against later conflicting applications

- Application for Principal Register (except Madrid Protocol extensions) can later be amended to instead be for Supplemental Register

Supplemental Register

The Supplemental Register is intended for marks that are currently unregistrable on Principal Register but are still potentially capable of distinguishing the applicant’s goods or services (and are not wholly functional). (§ 23). Merely descriptive terms that have not developed secondary meaning are accepted. These registrations often stem from applications that were refused registration on the Principal Register, due to mere descriptiveness, and then amended to be for the Supplemental Register instead. But generic terms are not accepted because they are never capable of serving a source-identifying function. Also, marks that conflict with a prior mark cannot be registered on the Supplemental Register.

Applications for the Supplemental Register cannot have merely an intent-to-use filing basis at the time of initial U.S. filing. Also, the Supplemental Register is not available for Madrid Protocol extensions (§ 66(a))—a new and separate U.S. application is needed instead. But actual use or Paris Convention foreign priority are available filing bases for a Supplemental Register application.

A Supplemental Register registration has limitations compared to one on the Principal Register. Most significantly, registration on the Supplemental Register does not establish any presumption of exclusive rights or proprietary interests in a mark. Consequently, it cannot be used to block importation of goods bearing identical or similar marks into USA. (§ 28). And a Supplemental Register registration (alone) is inadequate as the basis for cybersquatting actions and private marketplace exclusions. A Supplemental Register registration can also never achieve incontestable status. While a Supplemental Register registration can be asserted in an infringement, opposition, cancellation, or cybersquatting action, the owner would need to introduce evidence of ownership and secondary meaning to prevail (as with common law rights).

However, seeking and obtaining a registration on the Supplemental Register still provides the certain benefits to the applicant/registrant, including:

- Enables use of ® symbol (§ 29)

- Mark listed in searchable records and can be considered by USPTO against later conflicting applications

- No opposition period before registration (§ 24)

It is not possible to later “convert” a registration on Supplemental Register to one on the Principal Register. Instead, a new application for the Principal Register is needed. Overlap between Principal and Supplemental Register applications and registrations is permissible. (§ 27).

Filing Bases

As part of the requirements for a complete application (37 C.F.R. § 2.32), all new U.S. federal applications for registration must specify at least one filing basis (37 C.F.R. § 2.34):

- Use in commerce in USA (§ 1(a))

- Intent-to-use (ITU) (§ 1(b))

- Pending foreign application (§ 44(d))

- Granted foreign registration (§ 44(e))

- Madrid Protocol extensions (§ 66(a))

Each of these filing bases are discussed further below. Multiple filing bases are permitted in a given application. For example, an applicant can claim different filing bases for different goods/services. Also, an applicant can claim both foreign priority and actual use or and intent-to-use (in the USA) for the same goods/services. In some situations, a filing basis can be amended after filing.

The USPTO provides example timelines for applications based on the various different filing bases.

All applications for the Supplemental Register must be based on actual use in commerce in the USA (§ 1(a)) or a foreign priority application or registration (§ 44(d) or (e)). Supplemental Register applications cannot rely on an intent-to-use basis (§ 1(b)) at the time of initial U.S. filing. Also, the Supplemental Register is not available for Madrid Protocol extensions (§ 66(a)).

Actual Use in Commerce: § 1(a)

The first filing basis is actual use (§ 1(a)). This requires that the applied-for mark is already in actual (bona fide) use in commerce in the USA with the associated goods/services. Verification of use is required.

Use in commerce with goods means: (1) the mark is placed on the goods, packaging for the goods, or displays associated with the goods (including webpage displays), and (2) the goods are actually being sold or transported in commerce in USA. Use in commerce with services means: (1) mark is used in the sale, advertising, or rendering of the services, and (2) the services are actually being rendered in commerce in USA. Token or sham sales are not sufficient. Also, mere preparations to use a mark in the future do not constitute actual use.

An application based on actual use must specify (37 C.F.R. § 2.32):

- applicant’s name, domicile, and citizenship (for businesses, include the country of incorporation and type of corporate entity)

- date of applicant’s first use of the mark anywhere (including prior foreign use) — specify separate dates if different for application with multiple classes of goods/services

- date of applicant’s first use of the mark in commerce in or with the USA — specify separate dates if different for application with multiple classes of goods/services

- identification of the good(s)/service(s) with which the mark is used, and applicable international (Nice) classification(s)

- the mark

- if the mark contains non-English wording, English translation(s) are required; and if the mark includes non-Latin characters, it is required to submit a transliteration of those characters and either a translation of the transliterated term in English or a statement that the transliterated term has no meaning in English

- for graphical marks, an image must be provided in *.jpg format and should have a length of 250-944 pixels and a width of 250-944 pixels (if scanned, at 300-350 dots per inch); the image must be in color if color is claimed as a feature of the mark; a description of the mark is also required if not in standard characters (that is, if not a pure word mark)

- specimen(s) evidencing use of the identified goods/services in commerce in the USA or between the USA and a foreign country (foreign trade)

In order to claim actual use, specimen(s) evidencing use in commerce in each class are required at the time of filing. The types of acceptable specimens vary for goods and services. When multiple classes of goods and services are identified, multiple specimens are often necessary. Specimen requirements are discussed in more detail below.

Advantages of a § 1(a) basis:

- Presumption of validity and ownership of mark back to claimed date of first use in commerce in or with the USA (plus notice of the same)

- Less need for later actions/fees in application

Disadvantages of a § 1(a) basis:

- None, assuming requirements are met (acceptable specimen(s) of use constitute a key requirement; claim of acquired distinctiveness/secondary meaning potentially subject to later dispute, if relied upon to register a descriptive mark on the Principal Register)

Intent-to-Use (ITU): § 1(b)

Another possible filing basis is intent-to-use (§ 1(b)). In an ITU application, the mark has not yet been used in commerce in USA with the associated goods/services but the applicant has a bona fide intention, under circumstances showing good faith, to do so and is entitled to do so. Verification of the intention to use is required.

An ITU application must specify (37 C.F.R. § 2.32):

- applicant’s name, domicile, and citizenship (for businesses, include the country of incorporation and type of corporate entity)

- identification of the good(s)/service(s) with which the mark is intended to be used, and applicable international (Nice) classification(s)

- the mark:

- if the mark contains non-English wording, English translation(s) are required; and if the mark includes non-Latin characters, it is required to submit a transliteration of those characters and either a translation of the transliterated term in English or a statement that the transliterated term has no meaning in English

- for graphical marks, an image must be provided in *.jpg format and should have a length of 250-944 pixels and a width of 250-944 pixels (if scanned, at 300-350 dots per inch); the image must be in color if color is claimed as a feature of the mark; a description of the mark is also required if not in standard characters (that is, if not a pure word mark)

Recommendation: An ITU application requires a certification of the applicant’s good faith intention to use the mark, but it is not required to submit any documentary evidence supporting that intention with an application. However, a best practice is for the applicant to privately retain copies of detailed written business plans evidencing the intent to use the applied-for mark as of the filing date. If someone later opposes registration or seeks cancellation, perhaps many years later, such evidence may be necessary to corroborate the original certification of an intention to use the mark and not merely to reserve it (that is, not merely to block others’ use). Such evidence can also help disprove allegations of fraud regarding a certification of an intention to use the mark.

After filing, the applicant must submit a statement of use with specimen(s) evidencing actual use within six (6) months of a notice of allowance. The deadline for the statue of use is extendable in 6-month increments upon the payment of official fees. A maximum of five (5) extensions are available (for up to 30 additional months), meaning the statement of use must be filed no later than 36 months after the notice of allowance. A first request for an extension of time to file a statement of use is freely available, but each subsequent extension request must also include a showing of good cause. Good cause can be shown by specifying the applicant’s ongoing efforts to make use of the mark, such as product or service research or development, market research, manufacturing activities, promotional activities, steps to acquire distributors, steps to obtain required governmental approval, or other similar activities, such as efforts to secure funding. In the alternative, a satisfactory explanation for the failure to make such efforts may be submitted, although this alternative will rarely apply. Examples of activities that would not be acceptable include physical illness or disability and lack of staff and resources due to economic downturn. Additionally, good cause may be shown (but only a single time) by asserting that the applicant believes it has made valid use of the mark in commerce in the USA and either is in the process of preparing a statement of use but may need additional time to file it, or is concurrently filing a statement of use but is requesting the extension of time in case the original statement of use is found defective (this latter approach is called an insurance extension).

For foreign applicants, an ITU application may be worthwhile if there is no suitable foreign priority application or registration but preparations for use of a mark in the USA are underway. If actual use in begins in the USA, it is sometimes advantageous to promptly amend the ITU application to claim an actual use (§ 1(a)) basis rather than waiting for an allowance and later filing a statement of use.

Advantages of a § 1(b) filing basis:

- Can secure priority (constructive use) as of ITU application filing date

- Provides a period of up to approximately three (3) years to establish actual use

- Can be used in addition to a § 44 basis (priority claim to foreign application or foreign registration)

- Can amend § 1(b) filing basis to a § 1(a) basis (actual use) before a notice of allowance is received

Disadvantages of a § 1(b) filing basis:

- Will not register unless and until use in commerce in USA is established

- In absence of actual use in commerce in the USA, no enforceable rights merely because ITU application is pending

- May be more costly due to need for later statement of use

- Must pay for six-month extensions of time to submit statement of use with specimen(s) more than six (6) months after notice of allowance; maximum of five (5) extensions (30 additional months)

- Claim of bona fide intention to use as of filing date potentially subject to later dispute (especially if no written records retained)

Priority to Pending Foreign Application: § 44(d)

An application for a mark used or intended for use in the USA can claim priority to filing date of foreign application (from a country that is a party to an applicable treaty, namely, the Paris Convention, provided that the applicant’s country of origin is also a party). The applicant must have a good faith (bona fide) intention to use the mark in commerce in USA with the associated goods/services and be entitled to do so. Verification of that intention is required.

In order to claim priority to a prior foreign application, the U.S. application must be filed within six (6) months from the date the foreign application was first filed. If that time period has already passed, then a §§ 1(a), 1(b), or 44(e) filing basis must be used instead.

A § 44(d) foreign application provides a filing basis to obtain a priority filing date, only, but not a basis for subsequent publication or registration. In other words, § 44(d) provides merely a basis for filing but not for registration. The applicant must subsequently either perfect a § 44(e) claim based on registration of the cited foreign priority application or amend the application to assert an ITU or actual use basis (the latter two both requiring actual use in the USA in order for a registration to issue).

An application based on a claim of priority to an earlier foreign application must specify (37 C.F.R. § 2.32):

- applicant’s name, domicile, and citizenship (for businesses, include the country of incorporation and type of corporate entity)

- serial number(s) of foreign priority application(s)

- can specify multiple foreign priority applications by good/service

- for each foreign priority application, also:

- specify filing date and country of first regularly filed foreign application; or

- state that the application is based upon a subsequent regularly filed application in the same foreign country and that any prior-filed application has been withdrawn, abandoned, or the like and has not served as a basis for a right of priority

- identification of the good(s)/service(s) with which the mark is intended to be used, and applicable international (Nice) classification(s):

- may not exceed the scope of the identification in the foreign priority application, but certain other differences in identifications permitted or required (for instance, deletion of goods/services)

- additional goods/services can be included based on a different filing basis (§§ 1(a) or 1(b))

- the mark

- if the mark contains non-English wording, English translation(s) are required; and if the mark includes non-Latin characters, it is required to submit a transliteration of those characters and either a translation of the transliterated term in English or a statement that the transliterated term has no meaning in English

- for graphical marks, an image must be provided in *.jpg format and should have a length of 250-944 pixels and a width of 250-944 pixels (if scanned, at 300-350 dots per inch); the image must be in color if color is claimed as a feature of the mark; a description of the mark is also required if not in standard characters (that is, if not a pure word mark)

- optional: if multiple filing bases are claimed for the identified goods/services, can specify no intent to rely on subsequent grant of foreign registration and only wish to assert a valid claim of priority (that is, applicant wishes to claim priority earlier than the U.S. filing date but does not intend to wait for foreign priority application to register)

Recommendation: An application based on a foreign priority application requires a certification of the applicant’s good faith intention to use the mark in the USA, but it is not required to submit any documentary evidence supporting that intention with a U.S. application. However, a best practice is for the applicant to privately retain copies of detailed written business plans evidencing the intent to use the applied-for mark in the USA as of the U.S. filing date. If someone later opposes U.S. registration or seeks cancellation, perhaps many years later, such evidence may be necessary to corroborate the original certification of an intention to use the mark in the USA and not merely to reserve it (that is, not merely to block others’ use). Such evidence can also help disprove allegations of fraud regarding a certification of an intention to use the mark in the USA.

It is not necessary to submit a copy of the foreign priority application to the USPTO. However, a copy should still be provided to U.S. counsel to allow for verification of the priority application filing particulars.

Note that the USPTO may require broad identifications of goods/services from a foreign application to be more definite and specific (narrower). Identifications that are acceptable in other countries may not be in the USA. For example, the USPTO will generally refuse attempts to identify goods or services using international class headings and will insist upon narrower identifications of specific goods and services. It is also possible to voluntarily amend identifications of goods/services to be more specific or to omit certain goods/services, such as to omit some goods or services identified in the foreign application that are not intended to be used in the USA.

Advantages of a § 44(d) filing basis:

- Secure priority (constructive use in USA) as of foreign application filing date

- priority foreign filing date retained even if foreign application abandoned

- Actual use in commerce in USA not required for filing or for registration (unique to foreign priority claims)

- Specimen(s) and statement of use not required

- No official fees to keep application suspended awaiting foreign registration (unlike ITU extension fees)

- Eligible for Supplemental Register

Disadvantages of a § 44(d) filing basis:

- Relatively short time to claim priority (6 months)

- U.S. registration granted only after foreign application is granted (or a different basis for registration asserted)

- foreign registration delays may result in suspension of application in USA

- In absence of actual use in commerce in the USA, no enforceable rights until U.S. registration granted

- Intention to use the mark in the USA might later be disputed

Priority to Granted Foreign Registration: § 44(e)

An application can claim priority to a granted foreign registration under § 44(e). To do so, the applicant must have a good faith (bona fide) intention to use the mark in commerce in the USA with the associated goods/services and be entitled to do so. Verification of the intention to use the mark in the USA is required.

An application based on a claim of priority to a foreign registration must specify (37 C.F.R. § 2.32):

- applicant’s name, domicile, and citizenship (for businesses, include the country of incorporation and type of corporate entity)

- registration number(s) and registration date(s) of valid foreign priority registration(s) in country of origin

- for an old registration, also specify details of renewal (to show that the foreign registration is still in force)

- can specify multiple foreign priority registrations by good/service

- a true copy of each foreign registration (or recent renewal certificate) relied upon

- must provide English translation of foreign registration(s) if in other language

- certified copy of foreign registration generally not required but copy must be of certificate and not a database printout, etc.

- good(s)/service(s) with which the mark is intended to be used, and applicable international (Nice) classification(s)

- may not exceed the scope of the identification in the foreign priority registration, but certain other differences in identifications permitted or required (for instance, deletion of goods/services)

- additional goods/services can be included based on a different filing basis (§§ 1(a) or 1(b))

- the mark

- if the mark contains non-English wording, English translation(s) are required; and if the mark includes non-Latin characters, it is required to submit a transliteration of those characters and either a translation of the transliterated term in English or a statement that the transliterated term has no meaning in English

- for graphical marks, an image must be provided in *.jpg format and should have a length of 250-944 pixels and a width of 250-944 pixels (if scanned, at 300-350 dots per inch); the image must be in color if color is claimed as a feature of the mark; a description of the mark is also required if not in standard characters (that is, if not a pure word mark)

Recommendation: An application based on a foreign priority registration requires a certification of the applicant’s good faith intention to use the mark in the USA, but it is not required to submit any documentary evidence supporting that intention with a U.S. application. However, a best practice is for the applicant to privately retain copies of detailed written business plans evidencing the intent to use the applied-for mark in the USA as of the U.S. filing date. If someone later opposes U.S. registration or seeks cancellation, perhaps many years later, such evidence may be necessary to corroborate the original certification of an intention to use the mark in the USA and not merely to reserve it (that is, not merely to block others’ use). Such evidence can also help disprove allegations of fraud regarding a certification of an intention to use the mark in the USA.

Any foreign registration relied upon for a U.S. registration basis (including for perfecting a § 44(d) filing basis) must be from the applicant’s “country of origin” (§ 44(c)), which is (1) the country where owner has a bona fide and effective industrial or commercial establishment, (2) the country where the owner is domiciled, or (3) the country in which the owner is a national. Under this requirement, a corporate applicant’s country of origin can be different from the country in which its business is incorporated. An applicant can also have multiple countries of origin.

Advantages of a § 44(e) basis:

- No time limit for use as a U.S. filing basis

- date of foreign registration irrelevant to timing of claiming priority in a new U.S. application as long as foreign registration is still in force

- Actual use in commerce in USA not required for filing or for registration (unique to foreign priority claims)

- Specimen(s) and statement of use not required

- Can claim both § 44(d) and § 44(e) bases, if foreign priority registration filed and granted in prior 6 months

- Eligible for Supplemental Register

Disadvantages of a § 44(e) basis:

- Priority only accrues as of date of U.S. filing date (but not to the foreign registration’s foreign application filing date, unless a § 44(d) priority claim was timely made—see above)

- In absence of actual use in commerce in the USA, no enforceable rights until U.S. registration granted

- Intention to use the mark in the USA might later be disputed

Madrid Protocol Extension: § 66

Madrid Protocol international applications are filed with (or forwarded to) WIPO’s International Bureau (IB) and then protection is extended to the USA. That context, a § 66 filing basis is already established by the IB before the extension is transmitted to the USPTO, via applicant submission of form MM18 (which contains a verification required with any international application designating the USA). Representation by a U.S.-licensed attorney is required for Madrid extensions to USA, even though the Madrid international application can be filed with the IB by foreign counsel.

Although the Madrid Protocol centralizes and streamlines some aspects of filing, the USPTO makes independent substantive determinations regarding the registrability and renewal of registrations (extensions) in the USA. Regardless of prior treatment (including issuance of an International Registration), the USPTO can still issue an office action and still refuse U.S. registration. That is because the Madrid Protocol is only a filing treaty but is not a substantive law harmonization treaty. Additionally, post-registration filings asserting current use of mark are still required at USPTO in addition to 10-year renewals at the IB.

Advantages of Madrid extension to the USA (§ 66 basis):

- Efficient centralization of filing international application for extension to USA and other countries

- Actual use in commerce in USA not required for initial extension request or for extension registration (unique to foreign priority claims)

- Six-month office action response deadlines (without extension of time fees)

Disadvantages of Madrid extension to the USA (§ 66 basis):

- Post-grant filings required with both USPTO and IB to renew/maintain U.S. extension

- Cannot amend Madrid extension application to be for the Supplemental Register (new non-Madrid U.S. application required instead)

- Cannot amend the mark in any way (even for slight, non-material changes)

- Classification cannot be changed from those assigned by the International Bureau (unless the IB corrects the classification), and classes cannot be added and goods or services cannot be transferred (reclassified) from one class to another

- In absence of actual use in commerce in the USA, no enforceable rights until U.S. extension registration granted

- Intention to use the mark in the USA might later be disputed

- Subject to potential cancellation both in the USA as well as through cancellation, restriction, expiration, or abandonment of the foreign Basic Registration or Application from which extension to the USA is based within the first five (5) years (a “Central Attack”)

- Ownership can only be transferred to an entity with a business or domicile in – or is a national of – a Madrid System member state (Article 2(1); Rule 25(2)(a)(iv))

False Statements to Obtain Registration Are Illegal

U.S. registrations procured by fraud are invalid and subject to cancellation. (§ 14(3)). Any person (or company) who procures a registration by a false or fraudulent declaration, representation, or submission is liable in a civil action (lawsuit) for damages sustained by another as a consequence. (§ 38). Presenting any document to the USPTO by signing, filing, submitting, or later advocating by any person, whether a practitioner or non-practitioner, constitutes a certification that all statements made therein of the party’s own knowledge are true and that (after an inquiry reasonable under the circumstances) all allegations and other factual contentions have evidentiary support. (37 C.F.R. §§ 2.193(f) and 11.18(b)). Also, anyone who knowingly and willfully makes any materially false, fictitious, or fraudulent statement or representation to USPTO can be convicted of a crime and fined, imprisoned up to 5 years, or both (18 U.S.C. § 1001(a)).

The USPTO also uses of show cause orders and subsequent administrative sanctions to address false and fraudulent trademark applications and registrations.

IMPORTANT: All assertions and verifications of use a mark in commerce in the USA or intention to do so, plus all other statements to the USPTO, must be truthful!

Regardless of which filing bases apply to a given application for registration, it is crucial that all assertions are truthful and accurate. Applicants and their foreign counsel must conduct a reasonable investigation of all relevant facts in order to allow truthful certifications, verifications, and other statements to be made in U.S. trademark cases.

Identifications of Goods and/or Services

An application must identify the goods/services that the mark is actually used with in commerce, or for which there is a good faith intention to use the mark with in the USA, for which registration is sought. Identifications of goods and/or services must be grouped according to the International (Nice) Classification system. Each additional class carries an additional official fee, although the number of goods or services identified within a given class generally does not affect official fees. An applicant can identify fewer goods and services in a given application, for various reasons. But it is not permitted to include goods/services merely to reserve a mark for more goods/services (in the absence of use or bona fide intention to use the mark with those goods/services).

The basic requirements for an acceptable identification in a U.S. trademark application are the following:

- It describes the goods and/or services so that an English speaker could understand what the goods and/or services are, even if the grammar or phrasing is not optimal;

- It meets the standards (not necessarily the language) set forth in the ID Manual;

- It is not a class heading; and

- It is in the correct class, that is, there is no language in the identification that makes classification difficult or ambiguous, and each class lists goods or services that clearly belong in a single class.

The USPTO tends to require narrower and more specific identifications of goods and services than many other countries. Overly broad or vague identifications are frequently refused as being indefinite. In the USA, it is not permitted to use the short title of an international class or international class headings to encompass all goods or services in the given class. Terminology that is broad enough to span multiple international classes is also considered indefinite. Open-ended terminology like “including,” “such as,” “and similar goods,” “and related goods,” “products,” “concepts,” “like services,” and “etc.” is considered indefinite and is almost always unacceptable. Furthermore, if the filing basis is (exclusively) priority to a foreign application or registration, then the U.S. identification(s) cannot be broader.

The USPTO has an online Acceptable Identification of Goods and Services Manual (ID Manual) that provides guidance about acceptable terminology to identify goods and services. The ID Manual is meant to provide standards for acceptable identifications, but its example entries are not the only possible acceptable identifications of goods and services. That is, just because the wording of an identification departs from entries in the ID manual does not necessarily mean that wording is unacceptable.

Semicolons should generally be used in identifications to separate distinct categories of goods or services within a single class. Commas should generally be used to separate items within a particular category of goods or services. The terms “namely,” “consisting of,” “particularly,” “in particular,” and “in the nature of” are considered definite and are preferred to set forth an identification that requires greater particularity. This takes the form of broad introductory wording followed by the transitional wording set off by commas, followed by a listing of the specific goods or services set forth with particularity. For example, “clothing, namely, hats, sweaters, and jeans” is an acceptable identification of goods in Class 25. Use of alternate terminology or a translation in a parenthetical is usually not permitted, though there are some exceptions.

Explicit exclusions, field of use restrictions, and other narrowing or limiting terminology is often permissible. However, wording attempting to distinguish other international classes, such as “included in this class,” “belonging in this class,” or “excluding goods/services in other classes,” is not permitted in the USA.

Formulating identifications of goods and services is more of an art than an exact science. An experienced U.S. trademark attorney can help establish the wording of identifications that both account for USPTO practices and meet the applicant’s (global) filing strategy. USPTO trademark examiners may not always agree with an applicant or applicant’s attorney about what is an acceptable identification, although it is usually possible for the examiner and application to reach agreement on suitable identification language. Clarifying or limiting amendments to identifications are fairly liberally permitted after initial filing, so long as the amended wording does not expend or broaden the scope of the goods/services.

Specimens

A specimen is evidence of actual, real-world use of a trademark (or service mark) submitted to the USPTO, such as a photo of a product bearing the mark. It is evidence of what consumers encounter when considering whether to purchase the branded goods or services. For U.S. applications with an actual use (§ 1(a)) or intent-to-use (§ 1(b)) basis, the USPTO requires specimens both to initially obtain a registration and to maintain an existing registration (that is, for renewal).

For new applications with an actual use (§ 1(a)) filing basis, a suitable specimen is required at the time the application is filed. For ITU (§ 1(b)) applications, it is obviously not possible to have a specimen at the time of filing but a specimen and Statement of Use is eventually required after a Notice of Allowance before a registration can issue.

Specimens are not required for new U.S. applications based on foreign priority or that are Madrid extensions to the USA. The absence of a specimen requirement is a major benefit to foreign applicants replying on some form of foreign priority. However, a specimen will be required between the fifth and sixth (5th-6th) years of registration in order to maintain a U.S. registration, regardless of any foreign priority claim.

We turn now the formal requirements for what constitutes and acceptable specimen. There are some general requirements that apply to all specimens. What all the requirements have in common is that they look at the branding a U.S. consumer is presented with when considering purchasing the goods or services. These considerations take into account industry norms. The Trademark Office will scrutinize a specimen to ensure that it is acceptable under current guidelines. Submitting an unacceptable specimen will, at a minimum, delay registration.

First, an acceptable specimen must show the mark used in a way that consumers would perceive it as a source indicator—something that allows consumers to identify and distinguish goods or services emanating from different manufacturers, sellers, or producers. In that sense it must function as a mark.

One consideration is whether usage of the mark is prominent enough. If the mark is used only in passing or is difficult to identify amidst other things then the specimen is probably not acceptable. There must also be a direct association between the mark and the identified goods or services. A label or tag unattached to anything that shows only the mark but no other information fails to make that association.

Another consideration is proper usage. A term used generically or merely to provide information about the goods or services, or a graphic used merely for ornamentation or decoration, is not functioning as a mark.

It is also necessary for a specimen to show a real use. A specimen cannot be a mock-up, printer’s proof, digitally altered/fabricated image, rendering of intended packaging, or draft of a website that shows how a mark might appear. For instance, a computer-generated image of what a product is supposed to look like for marketing/advertising purposes or to seek investors for a business is not acceptable. It is helpful to think of a specimen as evidence that is representative of actual use that is already occurring. But anything that only portrays planned or theoretical use is not acceptable as a specimen.

Specimens must also correspond to usage with the particular goods and services identified in an application (or registration). A specimen must also show the same mark identified in the application or registration. Usage of a given mark with one good or service will not suffice as evidence of usage with an entirely different good or service. If there are multiple classes of goods or services in a given application (or registration), then multiple specimens are usually required—unless a single specimen happens to provide evidence of use of multiple goods or services.

The particular sorts of evidence acceptable as specimens will depend on whether it is for a trademark (for goods) or a service mark (for services). Those different goods/services requirements are taken up below (and here).

| Acceptable as Specimen for Goods | Unacceptable as Specimen for Goods |

|---|---|

| Photo of mark on product itself or attached tag/label | Mock-ups/digital renderings/altered images |

| Photo of mark on product packaging/container | Package insert not visible at time of purchase |

| Printout or screenshot of a web page where the product can be purchased (for example, showing “Add to cart” or cart/bag icon) | Web page, brochure, or catalog with no way to purchase product |

| Copy from catalog page where ordering information is provided (for example, “Call this number to place an order”) | Copy of magazine advertisement |

| Screen shot of web page for downloading installable software | Receipt or invoice confirming prior purchase |

| Installable software in-app screen capture | Business card |

A typical form of an acceptable trademark specimen for goods is a photograph of a product bearing the trademark on an attached label or tag. A photo of the trademark stamped or imprinted on products themselves or on their packaging or container is also common and acceptable. But a package insert bearing the mark that is not visible to customers is generally not acceptable. And, when it comes to goods, mere advertising is generally not acceptable as a specimen—this is probably the most frequent area of misunderstanding.

A display associated with the goods may or may not be acceptable as a specimen. Examples of displays of goods include in-store displays, catalogs, and web pages. To be acceptable, a display specimen must show use of the mark (a) directly associated with the goods and (b) that display usage must be at the point-of-sale. Typical e-commerce “shopping cart” and “shopping bag” buttons and icons shown near the goods meet point-of-sale requirements. But “contact us for more information” or “where to buy” links are insufficient because they are considered to require additional steps before a purchase can be made. The USPTO looks at “point-of-sale” rather strictly by analyzing whether and how ordering information is provided. Web pages, in particular, sometimes fail to meet all the requirements. Acceptability can depend upon web page layout.

| Acceptable as Specimen for Services | Unacceptable as Specimen for Services |

|---|---|

| Screen shot of web page mentioning services | Screen shot of web page that does not mention the services |

| Copy of magazine ad or brochure mentioning services | Copy of magazine ad or brochure that does not mention the services |

| Sign-in screen capture for online, cloud-based software platform (SaaS/PaaS) | Screen capture of online software not showing the mark |

| In-app screen capture showing use of non-downloadable software | Screen shot of web page to download installable software |

| Copy of business card or letterhead referencing services | Copy of business card that does not mention the services |

| Photo of service vehicle bearing the mark | Photo of service vehicle not showing the mark |

| Invoice with service details | Blank form for invoice or receipt that does not describe the services |

A service mark specimen must show the mark as actually used in the sale of the services. But a wider range of specimens are accepted for services than for goods. Acceptable specimens for services show use in the performance or rendering of the services or in the advertising of the services. A typical form of an acceptable service mark specimen is a web site printout or screen capture that shows the mark in direct association with a description of the services as part of an online advertisement. But even though a broader range of specimens can be used for service marks for services than for trademarks on goods, not anything will suffice. The USPTO provides a number of helpful examples of acceptable and unacceptable service mark specimens.

For specimens for both goods and services, the date the specimen was captured matters. For new trademark applications, a specimen must be recent, although there is no specific time frame applied to what is or is not recent. Specimens used to maintain existing registrations must be current, meaning the specimen should be from the specific window of time in which proof of current use can be submitted (for example, between the fifth and sixth years of registration).

Whenever a web page screenshot or printout is used as a specimen, the date and URL (web page address) must be included. Ideally screenshots and printouts should be captured in a way that automatically includes that information. U.S. counsel should be able to capture a screenshot of a web site specimen in a suitable manner if the relevant URL is provided.

If a specimen is defective, there may be opportunities to submit a substitute. But failure to submit a proper specimen from the start might lead to loss of priority if a suitable substitute specimen (gathered on or before the date the U.S. trademark application was filed) is not available.

More information about acceptable specimens can be found in the Q&A article “What is an Acceptable Trademark Specimen?” or in this USPTO Presentation.

Signatures

U.S. trademark filings (“correspondence”) with the USPTO require signatures. There may be multiple signatures required for a given submission, both for the submission as a whole and for specific factual declarations/verifications/certifications. All such signatures constitute certifications. (37 C.F.R. §§ 2.193 and 11.18). The required form of these signatures is discussed below.

It is possible for attorneys to sign trademark filings and required declarations/verifications/certifications of relevant facts, such as to certify use in commerce. However, it is very much preferable for applicants/registrants to sign factual verifications directly rather than their attorney. In particular, the person who signs a verification or certification of facts should preferably be someone with firsthand knowledge of the facts and actual or implied authority to act on behalf of the owner. In the case of a “juristic entity”, meaning a company, certain documents (like an assignment) must be signed by someone with legal authority to bind the company—for example, a corporate officer (like a CEO), a managing member of an LLC, or a general partner of a partnership. When signing on behalf of a company, the person signing must list his or her title.

Nearly all filings with the USPTO are submitted electrically. For USPTO-required declarations/verifications/certifications in trademark matters, it is possible for a form to be sent electronically to the person signing, who can enter an electronic signature. The acceptable form of such signatures on (non-assignment) filings is for the signatory to personally type his or her name between leading and trailing forward slashes. The slashes are required—omitting them will cause the USPTO filing system to reject the signature and refuse submission. The following is an example of the proper signature format:

/First_Name Surname/

The USPTO does permit other forms of signatures on correspondence, including scanned copies of “wet” ink signatures and certain signatures made using commercial document-signing software.

Signature requirements for trademark assignments are not subject to USPTO regulations specifying the form of signature on correspondence. The electronic signature requirements discussed above using a typed name between slashes does not apply to trademark assignments. Instead, signature requirements under applicable contract law must be considered. A “wet” ink signature by hand is generally acceptable on a U.S. trademark assignment, and is the preferred form of an assignment signature. A digital signature made with a commercial e-signature system may be acceptable on a trademark assignment as well, although compliance with applicable e-signature laws (like ESIGN or UETA) may require special procedures. But, fortunately, assignments are generally unnecessary when filing a new U.S. trademark application in the name of the current owner, and needed only when there is a change in ownership after an application is filed or registered.

Maintenance and Renewals

U.S. trademark registrations can last indefinitely, provided there is continued use in commerce in the USA (or excusable nonuse) and the registration is both valid and renewed. The USPTO provides a post-registration timeline and Madrid Protocol equivalent that summarize requirements to maintain and renew U.S. registrations. Though the following discussion explains the major post-registration actions required by the registrant.

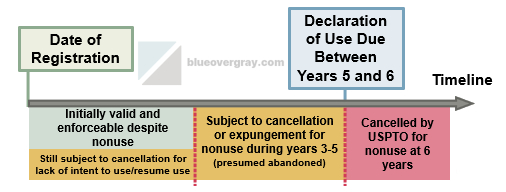

Both use of a mark in commerce and affirmative filings with the USPTO are required to maintain or renew registration in the USA. There are two distinct periods when USPTO submissions are required. First, a declaration of use or excusable nonuse (§§ 8 or 71) is required between the 5th and 6th years of registration (at which time a declaration of incontestability under § 15 may also be made in some circumstances). Second, between the 9th and 10th years of registration another declaration of use or excusable nonuse (§§ 8 and 9 or 71) is required for renewal of registration, and for at each successive 10-year period after that. Failing to submit any of these required declarations of use will result in cancellation of registration.

A declaration (affidavit) of use is a certification that the registered mark (even for Madrid Protocol extensions) is currently in use in commerce in USA for all identified goods/services. (37 C.F.R. § 2.161). It is necessary to submit specimen(s) for each class of goods/services along with the declaration of use as evidence of current use.

It is possible to amend a registration to delete unused goods/services in connection with making a declaration of use and renewal. (§ 7). However, official fee(s) apply (per class of goods/services) if an amendment is done with (“after”) the filing of a §§ 8 or 71 declaration of use, as well as a potential official deficiency fee if submitted after the normal submission period has passed. Though such official fees can be avoided by submitting an amendment to delete goods/services either before filing the declaration of use, or waiting until after the declaration is officially accepted.

A declaration (affidavit) of incontestability (§ 15) limits the possible grounds for cancellation of a registration in court. But a declaration of incontestability can only be filed if the registered mark has been in continuous use in the USA for five (5) consecutive years subsequent to registration, is still in use in commerce in the USA, and there is no pending proceeding or final adverse decision against mark. For registrations with a foreign priority claim for which use did not begin in the USA until after registration, these requirements may not all be met, meaning a declaration of incontestability cannot be made.

Excusable nonuse is an exception to the general requirements to certify use. If a registered mark is not in use with one or more identified goods/services, continued registration may be permitted if nonuse is due to special circumstances beyond the owner’s control rather than an intention to abandon the mark. (37 C.F.R. § 2.161(a)(6)(ii)). However, in order to claim excusable nonuse certain requirements must be met:

- list the goods/services with which the mark is not in use in commerce in USA

- date of the last use of the mark in commerce in USA

- approximate date when use in commerce in USA is expected to resume

- details regarding the reason for nonuse

- specific steps being taken to resume use in USA

There are some further considerations for Paris Convention and Madrid Protocol extensions. (§§ 44 or 66). Registrations based exclusively on foreign priority are presumptively subject to cancellation or expungement if use in commerce in the USA has not begun within three (3) years of registration even though a declaration of use to keep registration active is not due until the sixth (6th) year of registration. In practical terms, this means that the USPTO will not automatically cancel a registration for non-use until after six (6) years of registration, but a challenger can potentially seek cancellation or expungement after only three (3) years of registration. Additionally, such foreign priority registrations are subject to cancellation even immediately after registration for a lack of a bona fide (food faith) intention to use the mark in the USA (or to resume use following interruption in use), or due to fraud on the USPTO, genericness, or mere descriptiveness.

For Madrid Protocol extensions, the registrant must still must file a Section 71 declaration of use and accompanying specimen of use with the USPTO even though renewals are filed through WIPO’s IB. In other words, renewing a Madrid Protocol extension to the USA requires action by a licensed U.S. attorney to submit a declaration of use. Renewal submissions to the IB satisfy only part of U.S. renewal requirements. Cancellation, restriction, expiration, or abandonment of a foreign Basic Registration or Application upon with the Madrid extension tot he USA is based is also

Post-Registration Audits

A post-registration audit program applies to all current U.S. trademark registrations. This program is meant to remove from registration goods and services that are not actually in use. The USPTO may (randomly) select a registration for an audit if a certain number of goods/services or classes are identified in registration, based on the following criteria:

(a) The registration includes at least one (≥ 1) class with four or more (≥ 4) goods or services identified

OR

(b) The registration includes at least two (≥ 2) classes with two or more (≥ 2) goods or services identified

If a registration is selected for an audit, the USPTO will also review the acceptability of previously-submitted specimen(s) for any additional classes present in the registration. In other words, while the criteria above determine if a given registration is subject to audit review at all, once selected, the entire registration is subject to substantive review and not merely the classes with multiple goods or services.

When a registration is selected for an audit, the USPTO will send the registrant’s counsel an office action. In order to avoid cancellation of the entire registration, the registrant must submit proof of use for each good or service identified in the office action and address any deficiencies with a previously-submitted declaration of use.

More information on this audit program is available on the USPTO audit program web page and in these USPTO presentation slides.

Challenging Registration

There are various procedures available to challenge a registration or pending application. Applicants should be aware that their own application or subsequent registration might be challenged in one of these ways. Additionally, these procedures might be used to challenge a conflicting prior registration or application that is cited as a basis for refusal of your application, or to challenge a subsequent application or registration that may weaken your rights or that causes a likelihood of confusion.

Procedures to Challenge Pending Applications

- Letter of protest:

- Can submit evidence relevant to grounds for refusal

- Certain topics excluded (for example, the USPTO will not consider evidence of fraud or alleged prior common law rights)

- Deadline: must submit letter of protest before end of 30-day opposition period following publication (and ideally before publication), but for Madrid extensions must submit before 18-months after IB transmits application to USPTO

- See USPTO presentation slides

- Opposition:

- Conducted as an administrative trial at the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (TTAB) within the USPTO

- Deadline: within 30 days of publication (extensions available, but must be requested within original opposition period)

- Opposition is possible on any grounds that would preclude registration

- The most common reasons for opposition involve a likelihood of confusion with a prior registration and/or prior common law rights

- Concurrent use:

- Geographic restrictions within the USA

- Rare

Granted Registrations

- Cancellation:

- Conducted as an administrative trial at the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (TTAB) within the USPTO

- Cancellation can be sought on any grounds that would preclude registration, but the available grounds for cancellation are limited after five (5) years of registration

- The most common reasons for opposition involve a likelihood of confusion with a prior registration and/or prior common law rights

- Cannot seek cancellation at TTAB for mere descriptiveness after five (5) years of registration

- Ex parte Expungement:

- Can be requested by a third party but proceedings are only between registrant and USPTO (conducted via office action like original examination)

- Deadline: between 3-10 years of registration

- Limited exception: until December 27, 2023, expungement may be requested for any registration at least three (3) years old, regardless of the ten-year limit

- Grounds: mark never used with any or all identified goods/services

- Available against all U.S. registrations but especially significant as an alternative to an inter partes Cancellation proceeding for foreign-originating registrations (Madrid [§66] or Paris Convention [§44] cases) where proof of use is not required to initially obtain a U.S. registration

- Ex parte Reexamination:

- Can be requested by a third party but proceedings are only between registrant and USPTO (conducted via office action like original examination)

- Deadline: within 5 years of registration

- Grounds: mark was not used with any or all identified goods/services on or before either:

- the application filing date (when the underlying application was initially filed based on use of the trademark in commerce under §1(a)); or

- the later of the date that an amendment to allege use was filed or the date that the deadline to file a statement of use expired (when the underlying application was filed with an intent-to-use basis under §1(b))

- Only available against registrations with a §1 basis: actual use or intent-to-use (not available against registrations with a priority claim based on Paris Convention or Madrid Protocol)

- Interference (rare)

- District Court Lawsuit:

- A registration can be challenged (cancelled) in district court on any grounds but the available grounds are limited when the challenged registration is incontestable

- Challenger must have standing to sue

Misleading Notices and Scams