By Austen Zuege

Startup companies and early-phase businesses need to think about intellectual property (IP). It is through IP that startups can maintain exclusivity in the unique products and services they develop. This can help protect and preserve revenue streams as the business grows and expands. A lender can even be given a security interest in IP as collateral for a loan. IP also represents much of the intangible value of a startup. If the business or product line is sold, IP is a key intangible asset that the purchaser acquires. Also, investors will often look for and may even demand that IP protections be in place before investing in a startup. In any case, IP represents nearly the entire value of many startups. This makes it crucial think about patents, trademarks, copyright, and trade secrets. One catch is that if you don’t know much about IP you may not know what you are missing or where you are going wrong. The other catch is that obtaining and maintaining IP protection comes at a cost. Knowing when and where those costs are worthwhile is the key. What follows is an overview of common IP issues faced by startups to help inform decision-making.

Table of Contents

Patents

Many startups are founded to develop an invention. Patents can protect inventions. They help secure exclusivity. Investors and potential buyers interested in a startup will look for a patent portfolio. Patents may also provide marketing advantages. So it is crucial that startups consider patent protection from the start. Failing to pursue a patent application in a timely manner can result in loss of patent rights. In the U.S., there is a one-year grace period for patent filings. This means an inventor has up to one year to file a patent application after publicly disclosing or commercializing his or her invention. What are some examples? Disclosure in a journal article or other publication starts that one-year clock running. Public use of the invention also starts the clock. And a commercial sale or offer for sale of the invention will also start the clock, even if the sale was confidential and secret. But in many other countries there is no grace period (though foreign patent laws governing what triggers loss of rights vary by country). If patent protection in other countries is important or might become important in the future, consider filing a patent application before any public disclosure or commercialization.

In the U.S., there is a one-year grace period for patent filings

See 35 U.S.C. § 102(b)

There is also a need to win the race to the patent office. Patent rights generally go to the first inventor to file. If there are others concurrently working on similar technology, your startup could be unable to patent its inventions if someone else files a similar patent application before you. So there is some urgency to pursue patent protection quickly. If you wait, you might lose out on patent rights to someone who files a patent application on the same invention sooner. And that delay could even mean you are no longer considered the inventor but instead an infringer.

Patent rights are territorial. There is no such thing as an “international” patent enforceable in all countries. It is generally necessary to obtain a patent in each individual country where protection is desired—though there are some regional patent offices like the European Patent Office (EPO). Filing a U.S. patent application can allow foreign patent applications to later claim “priority” back to the earlier U.S. application. To do this under the Paris Convention treaty, the foreign applications must be filed within one year of the priority application. But, as already mentioned, pre-filing public disclosure of an invention may bar foreign patenting even though the grace period applies in the U.S. Another option to preserve foreign patent rights is a Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT) application. The PCT system, which is administered by an agency of the UN called the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO), acts like a clearinghouse to facilitate patent filings in participating countries. Although most countries participate in the PCT system, some notable non-participating countries (as of this writing) are Argentina, Taiwan (R.O.C.), and Venezuela. One advantage of a PCT application is that it can give you an additional 18 months to decide which foreign countries your startup wants to pursue patent protection in (compared to direct Paris Convention filings). You still need to enter individual countries to obtain enforceable patents rights there based on the PCT application, however.

A patent applicant has fairly wide latitude to determine the content of a patent application. Each one is essentially customized for the particular invention involved. This is not a matter of simply populating a blank application form. Because patents are a complex area of law, it is recommended to seek the assistance of a patent attorney to prepare a patent application. If your startup lacks the funding to hire a patent attorney, it may be undercapitalized. When startups rely on an inventor to draft the patent application, all too often the resultant scope of coverage is less than intended or the claims in the patent make enforcement against infringers difficult if not impossible. Indeed, U.S. Patent & Trademark Office (USPTO) materials even advise, “Inventors may prepare their own applications and file them in the USPTO and conduct the proceedings themselves, but unless they are familiar with these matters or study them in detail, they may get into considerable difficulty. While a patent may be obtained in many cases by persons not skilled in this work, there would be no assurance that the patent obtained would adequately protect the particular invention.” The real skill a patent attorney brings to the table is the ability to capture and convey what is really important about an invention. It can be false economy to avoid these early legal expenses when doing so may lead to long-term problems. Investors and potential purchasers of a startup will likely look unfavorably on a self-prepared patent or patent application. Money spent on a patent attorney is money well spent by startups developing inventions.

In some cases, there might actually be multiple patentable inventions embodied in a new product. For instance, a useful feature may be patentable in a utility patent while ornamental aspects of a commercial embodiment may be patentable in a design patent. Or there might be two different utility inventions present in distinct aspects of the same product. And ongoing development may result in improvements that are also patentable. It is generally not permitted to add “new matter” to a patent application after filing. That is to say, any substantive technical information is more or less set in stone—fixed—when a patent application is filed. Ongoing development may necessitate filing multiple patent applications to obtain desired protection for what amount to additional but later inventions. A patent attorney can help advise about filing strategies that might encompass multiple patent applications, because the best procedures to do so can be nuanced.

A patent attorney can also assist with a pre-filing patentability search and analysis. While it is not required to perform a pre-filing search, doing so is often beneficial. A search can uncover relevant “prior art” that may limit patentability. This allows you to focus your budget on inventions that are patentable rather than wasting further funds on unpatentable concepts. But a search also helps improve the quality of a patent application. Having search results on hand allows a new application to better highlight differences from the closest prior art. Improving the quality of a patent application with the aid of a patentability search can also help streamline the cost an effort involved during examination (“prosecution”) of the application.

For startups putting effort toward technical or scientific R&D, patents might be the single most important and valuable IP on the table. Though inaction might result in loss of patent rights. So it is important for startups to think about patenting early and on an ongoing basis. While obtaining patent protection in multiple countries involves considerable expense, some investors will scrutinize the breadth of jurisdictions where patent protection has been pursued. When seeking a patent attorney, note that patent law is a specialization. To be a “patent attorney” (or “patent agent”) requires passing the patent bar to practice before the U.S. Patent Office. Business attorneys are typically not registered patent attorneys. Your business counsel might be able to refer you to a patent attorney. Though you may wish to consider a patent attorney from a different firm than your business counsel. Some law firms specialize exclusively in patents and IP and may be able to provide tailored expertise to startups seeking to patent their inventions.

Trademarks

Trademarks (and service marks) can protect a brand that identifies a source of goods or services. Depending on the type of business, a startup may have one or more brands that identify its goods and services by way of a “mark”. A mark can be a word, a set of words, a graphical logo, a composite mark with both words and graphical elements, or all sorts of other non-traditional signs or symbols. Most importantly, a mark is something that consumers and potential customers would recognize as connoting the source of the goods or services. Trademark law helps to prevent customer confusion over the source of anything branded with the mark. In the U.S., there are both federal and state trademark laws. Generally federal trademark laws are the most important for a startup.

Trademark rights in the U.S. are tied to use in connection with commercial activity. Trademark rights can accrue to anyone actually using the mark. Registration of a mark is optional and can generally be sought at any time while the mark remains in use. Though in the absence of a federal registration trademark rights may be limited to the particular geographic market where the mark is used. It is possible to apply for federal registration on an intent-to-use (ITU) basis. In other words, you can file before actual use begins to help win the race for priority in the mark. But actual use is eventually required before the mark can be registered. Filing proof of use can be delayed up to about three years by paying extensions of time. For example, an ITU application is worthwhile if you are undergoing a long period of pre-release preparations, expending a lot on marketing around a product launch, or there is a significant risk someone else will adopt a similar mark.

Mark selection is important in determining whether or not it can be protected as a trademark. This is important regardless of whether you intend to register your mark or not. All too often startups will select a mark without first evaluating whether the mark is protectable or whether it raises infringement concerns. There is a tendency for company founders to become emotionally attached to their brands. Being forced to rebrand can be crushing. And rebranding costs and efforts only increase over time. So the best approach is to select a viable and suitably low-risk mark from the outset. This is often harder than it seems. It is typical to discover that your first choice for a brand will not work. Actually, it is not unusual to have to run through a fairly lengthy list of potential marks before finding one that is both available for your planned use (and also available in a suitable domain name) and legally protectable as a trademark.

The first user of a mark generally has superior rights. This means existing trademark uses limit the universe of marks that are available for adoption by a startup at any given point in time. Bear in mind that trademark rights are different from other kinds of names used in the business world. Registering a corporation (like “Acme, Inc.”) or an Internet domain name (like “acmeinc.com”) is usually possible despite anything already used by others based on slight variations in spelling, punctuation, or with the addition of extra letters or words. But those rather low thresholds for incorporating a business or registering a domain do not mean you are in the clear with respect to anyone else trademark rights.

Modern trademark laws prohibit more than just counterfeiting and knock-offs. Uses of marks that create a “likelihood of confusion” can raise infringement concerns even if the marks differ and even if the goods and services differ. Actual consumer confusion in the marketplace is not required. Although courts and the U.S. Trademark Office utilize an expansive multifactor analysis to assess likelihood of confusion, the two main considerations are (1) the similarity or dissimilarity of the marks and (2) the similarity or dissimilarity of the goods and services. It is possible for identical marks to coexist for different goods and services. Consider how DELTA is simultaneously a well-known mark for plumbing fixtures but also a well-known mark for air transportation services (and many other things). And, in some situations, geographically separate uses of identical or similar marks can sometimes coexist, or a prior user might consent to coexistence (likely subject to certain conditions meant to avoid customer confusion). But business and marketing people may struggle to assess similarity and likelihood of confusion objectively. There is a tendency to view other people’s rights narrowly (while perhaps viewing your own rights broadly) in a way that may be too self-serving to hold up under the law.

Also bear in mind that trademark rights are territorial. Rights in one country generally provide no exclusivity in another. But most countries have no use requirement like the U.S. Instead, many other countries follow a first-to-file system and may provide little or no rights based solely on use of a mark. Registration is therefore often more important abroad. If your startup will operate in other countries, trademark protection in each of those countries should be considered. It is possible to file a trademark application in a foreign country that claims priority to an earlier application or registration in your country of origin. While some trademark priority claims can be made at any time a foreign registration is in effect, a claim of priority to the foreign application filing date requires that an application be filed within six months. There is also something called the Madrid Protocol system that allows for trademark protection in one country to be extended to other participating countries in a semi-centralized manner.

It is a good idea to conduct a trademark search and analysis before selecting and adopting a mark. A search can help identify potentially conflicting marks. While a search is an added expense, it is always less expensive than re-branding or fending off infringement allegations. Keep in mind that it is highly common for your first-choice mark to already be in use by another entity. That is especially true for marks that are descriptive or suggestive.

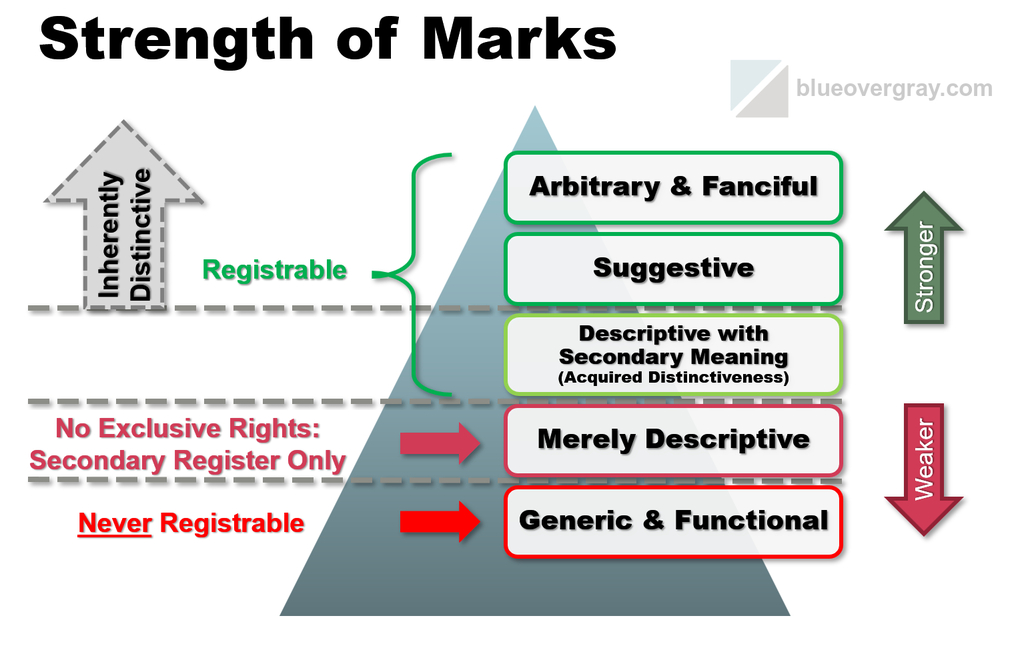

Aside from potential conflicts with other businesses’ existing marks, a mark must be distinctive enough to be protectable. There is a strength continuum. To be protectable a mark must meet certain thresholds on that continuum. Businesses, and especially startups with limited resources, often gravitate toward “weak” marks because they “sell themselves” and require little or no marketing effort to be understandable and recognizable to consumers. But the trade-off is that a weak mark provides little or no legal exclusivity. If you select a generic term, it can never be exclusively protected as a trademark no matter how much advertising effort or legal expense is put toward it. A mark that is merely descriptive will not be protectable upon adoption. Though a descriptive mark that acquires “secondary meaning” through extensive use and advertising over a sufficiently long period of time may acquire distinctiveness and become protectable. Whether a given mark is descriptive (or generic) depends on the goods and services with which it is used. Descriptiveness and genericness also depend on what consumers understand words in marks to mean. Suggestive marks are stronger than descriptive marks and are protectable from the start. Arbitrary and fanciful/coined marks are considered legally strongest. Suggestive, arbitrary, and fanciful/coined marks are all considered “inherently distinctive”.

Any mark, registered or not, should be used properly. In the most general sense, trademarks made up of words should be used like adjectives. It is a good idea to couple word marks with a generic term, or even insert the word “brand” too. For instance, say, “We sell EXAMPLE MARKTM widgets” or “We make EXAMPLE MARKTM brand widgets.” Actually, this is a great way to test if your trademark usage is proper. What you don’t want to do is use your mark in a descriptive or generic manner. That would suggest it is weak and potentially unprotectable. For instance, it is improper usage to say, “We sell example marks,” because this tends to indicate that “example mark” is the generic term for what you sell—and generic terms are not protectable as trademarks. Your usage should also be consistent. Don’t change the spelling or wording. For graphical marks, keep the colors, design, etc. consistent. Also consider using symbols to denote your marks. The symbols TM (for trademarks applied to goods) and SM (for service marks applied to services) can be freely used immediately after any mark you claim as your own—registration is not required to use those designations. The ® symbol designates a registered trademark—it should be used with a registered mark but must not be used with an unregistered mark.

Whether registration of a mark is worthwhile for a startup or not will depend. If the goods and services are industrial and the customer base is fairly narrow and specialized, and there will likely be few competitors entering the market, registration might be something to put off until later. Consumer goods and services directed to a wide customer base, especially one with unsophisticated consumers, will benefit more from registration. Some online marketplaces have policies that encourage trademark registration. And startups active online and on social media may be able to use a registration to demonstrate legitimate rights in a mark so as to help defend against takedown attempts by someone making a doubtful infringement claim or just seeking to attack a new competitor—although this is not an absolute defense. Also, if your startup is undergoing a big “launch” supported by considerable advertising then a registration, possibly on an intent-to-use (ITU) basis, may be worthwhile. A trademark registration can help protect marketing expenditures. If your startup will operate in foreign countries registration might also be important there because of territorial differences in trademark laws. For instance, having branded products made and exported from a foreign country may (or may not) constitute trademark use in that foreign country, making it important to consider obtaining trademark registration there.

Lastly, a word of caution. There are many scams involving trademarks. The basic scenario is that a scammer sends a misleading notice to a business that has applied for or registered a trademark. These tend to have an official-looking appearance. They ask for exorbitant amounts of money for actions that might not even be required to obtain or maintain a trademark. Some examples of these scams can be found here and here. Trademark attorneys are familiar with these scams. They can help your startup identify legitimate communications and fees.

Copyrights

Copyrights can be a maddening area of IP law. There are many counterintuitive aspects. Yet copyrights are implicated in everyday activities and copyright issues abound in online settings. Written text, photographs, and graphics are all examples of copyrightable works (though not everything is copyrightable). Software source code is treated as a textual work, just like book. When it comes to startup businesses, copyright ownership issues are most critical when core business activities involve software source code or conventional creative works like visual artworks, original music, audiovisual works, or the like. Avoiding copyright infringement is also important but this guide will focus on securing ownership of copyright in the startup context.

Copyright arises automatically from the time a work is fixed in a tangible medium of expression. You don’t have to do anything for copyright to arise. As soon as a work is created copyright exists. On the one hand, this simplifies things. Copyright arises without having to affirmatively do anything. But on the other hand, questions of who actually owns the copyright may be counterintuitive. And a registration may provide important enforcement benefits if obtained prior to infringement taking place.

By default, the copyright in any new work is automatically owned by the author, or jointly owned by all co-authors. An important exception for authorship and ownership under U.S. copyright law involves “work made for hire.” This aspect of copyright law is often misunderstood, even by attorneys! A copyrightable work prepared by an employee within the scope of his or her employment is deemed authored by and thus automatically owned from the outset by the employer. But vendors and even “internal” independent contractors do not fall within that definition. And if a startup founder-owner or other collaborator who might fall short of formally being employees is involved their works will not qualify either. What then? Parties can also agree in writing that a work will be a “work made for hire” but only for nine types of works enumerated in 17 U.S.C. § 101: (1) a contribution to a collective work, (2) a part of a motion picture or other audiovisual work, (3) a translation, (4) a supplementary work, (5) a compilation, (6) an instructional text, (7) a test, (8) answer material for a test, or (9) an atlas. Period. You cannot contractually expand those statutory types of “work made for hire”—though a common mistake is to try to do just that. In many situations, these nine types of work won’t apply. You then must obtain a written copyright assignment in order to obtain ownership.

“work made for hire”: This aspect of copyright law is often misunderstood

See 17 U.S.C. § 101

Copyright ownership is also distinct from possession of a copy of a work, even the sole “original”. A common mistake that businesses make is to hire a vendor who creates a copyrightable work while (incorrectly) assuming that they own the copyright merely because they received a copy and paid the vendor to create it. For instance, a startup might hire a photographer to take photos for a web site but never acquire copyright in the photos. Then sometime later, when an infringer copies those photos but the photographer cannot be found, the avenues to pursue the infringer may be frustratingly limited.

Another complexity is that copyright ownership issues also apply to vendors. A startup may hire a vendor believing all work will be done by the vendor’s employees when in fact the vendor subcontracts the work to others or utilize non-employee contractors. If copyright ownership is important to your startup, take efforts to ensure that the vendor has or obtains copyright ownership before purporting to assign those rights to your startup.

Copyright registration is optional. And registration can be pursued at any time during the term of copyright for a given work. However, copyright registration is generally a prerequisite to bringing an infringement lawsuit for any U.S. work (but not for foreign works). Copyright registration does provide some important perks. Registering before an infringement occurs or, in the case of “published” works, within three months of first publication, allows for an award of statutory damages and/or of attorney’s fees. Where the value of the work in question is small or just uncertain, having those remedies available can make a difference. Registration can be the difference between a copyright enforcement action being cost-prohibitive (and so unlikely) or, at a minimum, being a potent weapon that may encourage infringers to voluntarily cease infringement without having to formally sue them.

Because copyright applies to so many works that might be of negligible real value to a startup, registration is probably unnecessary in many situations. Though copyright registration should be considered for works that are of particularly high value or are particularly prone to infringement. There are group registration options that allow multiple works to be registered together. But group registrations are only available for certain types of works in certain situations. Also, registration tends to be simplest when done right after creation or first publication. Registrations sought long after a work was created or (possibly) published, especially works that are later versions of earlier works, can raise complex questions.

If you don’t acquire copyright ownership of a work a license can still allow its use. A license amounts to authorization from the copyright owner. Startups involved with software or other materials that will require later revisions should consider this issue closely. That is because copyright is a bundle of rights that allows the owner to control the creation of derivative works. Although licenses can be implied or given orally, it is much preferable to have a clear written license to allow revisions, additions, source code bug fixes, and other things that would constitute derivative works. It is important to maintain records of license authorizations. Those records might later turn out to be your main defense against an infringement claim that arises years later. But the departure of employees or changes in information storage systems can easily result in loss or misplacement of prior authorizations. In the software arena, also be aware that code dependencies may make licensing more complicated.

Lastly, copyright notices can be applied to any copyrighted work. It is not necessary to obtain a copyright registration to use a copyright notice. Copyright notices use the symbol © (or for phonorecords ℗ ), the word “copyright”, or the abbreviation “copr.” These notices can be added to your works with little effort. They have a number of advantages. The main one is that they let others know about your ownership claim to discourage infringement. But if you do use copyright notices be sure they include accurate information. For instance, make sure you correctly identify the actual copyright owner rather than, say, your brand name or an entity that someone casually but incorrectly assumes is the owner.

Trade Secrets

Trade secrets require no “registration” and they can potentially last indefinitely. Yet they do require efforts to ensure that they qualify for legal protections. There are three basic elements of a trade secret:

(1) it is not generally known to the public (and is not readily ascertainable by proper means);

(2) it confers economic benefit on its holder because the information is not publicly known; and

(3) the holder makes reasonable efforts to maintain its secrecy.

But trade secrets can be just about any type of information. They can encompass all forms and types of financial, business, scientific, technical, economic, or engineering information, including patterns, plans, compilations, program devices, formulas, designs, prototypes, methods, techniques, processes, procedures, programs, codes, customer lists, marketing and distribution strategies, etc. A famous example is the secret formula for COCA-COLA® soft drinks. But just because these types of information can be trade secrets doesn’t mean that in your startup they automatically will qualify.

The main thing to do to safeguard trade secret status for important information is to make reasonable efforts to maintain secrecy. There is no checklist for doing this. Determining what steps must be taken will depend on the circumstances and the nature of the information in question. But these efforts to maintain secrecy must always involve affirmative acts. At a minimum, you must be able to point to specific protective steps affirmatively taken to guard your startup’s trade secrets that go beyond normal business practices applied to all business information. A court will not let you get away with claiming that every piece of information generated by your startup is a trade secret. So start by narrowing your focus to information for which secrecy is truly most important. Then look at reasonable efforts to maintain secrecy of things on that shortlist.

Common affirmative measures to protect trade secrets include the following. But, alone, any one of these steps may be insufficient. Contracts or clauses in broader contracts pertaining to non-disclosure agreements (NDAs), confidentiality clauses, non-use, and/or non-circumvention can help maintain trade secret status while allowing necessary personnel access to information. And such agreements may benefit from further terms defining or otherwise acknowledging that certain types of information qualify as enforceable trade secrets—this may be helpful if you have to share trade secret information with a non-employee third party. Confidential materials can also be marked as such to explicitly make clear trade secret claims. Marking can be particularly important where materials are exchanged under an NDA with a customer or a supplier, manufacturer, or other vendor. More generally, make sure recipients of trade secrets understand your secrecy requirements. The principal “trust but verify” may be conceptually useful in that context. Access to trade secret materials can also be limited, which can help minimize risks of accidental or unintended disclosures. Computer/IT systems and physical spaces containing trade secret information should be secured and protected from unauthorized access. If your startup is operating out of a garage, basement, or other improvised space shared by roommates or family, or in a coworking or shared office space accessible to others, these access considerations are significant. Any departing employees should also be cut off from access to secret materials, which might require changing account login access to cloud storage systems, etc. If a startup has a revolving door of short-term employees or collaborators trade secret issues will take on heightened significance.

It is possible to abandon trade secrecy protections. So whatever protective measures your startup puts in place they must actually be followed. You will not be able to “un-ring a bell” and later claim as a trade secret something that was not kept secret in the first place or was publicly disclosed at some later point.

Employee agreements around trade secrets are possible and may be desirable but they may not be strictly required—some state laws even explicitly say that employee agreement are not required. When employers have trade secret provisions in employee agreements, they are often closely tied to non-compete clauses. Employee non-competes are governed by state laws and their enforceability varies considerably by state.

Federal trade secret law includes a whistleblower protection provision. In order to recover exemplary damages or attorney fees in a federal trade secret misappropriation lawsuit, an employer must provide notice of immunity (set forth in 18 U.S.C. §1833(b)) in any contract or agreement with an employee that governs the use of a trade secret or other confidential information. Such an employee notice must indicate that the employee shall not be held criminally or civilly liable under any Federal or State trade secret law for the disclosure of a trade secret that is made in confidence to a Federal, State, or local government official, either directly or indirectly, or to an attorney solely for the purpose of reporting or investigating a suspected violation of law; or is made in a complaint or other document filed in a lawsuit or other proceeding, if such filing is made under seal.

In the end, trade secret protections come down to vigilance. Because trade secret protections are highly context-dependent you may need legal advice to understand what measures are appropriate in your startup’s particular situation. But the amount of effort you put toward protecting them will depend on what you believe your secret information to be worth. While notoriously difficult to value, it is possible to say that trade secret rights are worth whatever you are willing to spend to enforce them.

Employee and Vendor Agreements

Just as important as taking steps to protect IP is taking steps to ensure ownership of that IP vests in the startup. For instance, ownership of potential patent rights in an invention accrue to the inventor or joint inventors as individuals by default (though at least one state and other countries alter this default rule by law). It is through written agreements that ownership is usually transferred to the startup or, in some specific instances, that ownership initially arises in the name of the startup. It is therefore important for a startup to obtain appropriate agreements if it wants to be the owner of the IP that pertains to its line of business–as opposed to ownership remaining with employees, contractors, or vendors. Such IP-related contractual terms can appear in employment agreements, master services agreements, product development agreements, joint development agreements, non-disclosure agreements (NDAs), purchase agreements, etc. IP ownership can also be transferred by way of a written assignment and authorization to use some or all of particular IP rights can be given by a license. Some agreements create an obligation to assign, which requires that a separate assignment be signed later on. Obligations to assign use language like “will assign” or “shall assign”. Other agreements create a present assignment or set forth a conditional assignment triggered by some later event (like completion of payment). Assignments that take effect immediately use language like “hereby assigns”.

Laws governing employee inventions and works of authorship will only apply if the person in question is actually an employee. In startups there might be ambiguity about employment status. A founder might own the business but may not be an employee if the startup provided no resources to invent or create the IP and is not paying that person any salary. Outside contractors/vendors are obviously not employees but independent contractors working in-house or on-site aren’t employees either. When startup businesses move quickly and have loose relationships with various collaborators, they can create a morass of IP ownership issues that may be challenging to sort out and fix after the fact. We must add to all this the ways IP law intersects with employment law. For example, the enforceability of employment agreements signed after employment begins varies state-to-state. That affects the enforceability of any IP terms in such agreements and the requirements to make agreement terms binding. For instance, some states require an explicit payment or benefit as “consideration” for a binding IP agreement signed after an employee has already started work. Continued employment alone is not sufficient in such states. So what works fine in one state may not in another.

NDAs are fairly common. They can be used to help preserve trade secret protections while disclosing information to someone on a confidential basis. For startups pitching ideas to potential investors, collaborators, vendors, and customers, NDAs can be very useful. In order for an NDA to be binding, just like any contract, it needs to be signed by someone with authority to do so. So if you are seeking an NDA from a company, make sure that someone with authority to bind the company signs it. Having a summer intern or salesperson sign it probably won’t be sufficient. But companies can delegate authority in all sorts of ways and one company may delegate authority to enter into NDAs in different ways. It is generally acceptable for a corporate officer, like the president or CEO, to sign on behalf of a company. For LLCs, it is generally acceptable for a member or managing member to sign on behalf of the LLC, though different states use different terms to name the persons with authority.

It is worth scrutinizing standard agreements to ensure that IP provisions deliver on your expectations. There is no one-size-fits-all approach. Having good IP legal advice can avoid lots of headaches down the road. While general business counsel might have certain standard agreement templates they can offer that include IP provisions, those stock forms may fail to account for unique circumstances and specific business plans, or are even based on misunderstandings of IP law. The key with IP-related agreements is often acting at the most opportune time. Trying to “fix” a problem by negotiating an agreement after work has begun, or is already complete, can present problems. One of those problems is a lack of leverage. Seeking to alter expectations in hindsight might be difficult if the other side feels it has no obligation or incentive to cooperate. Such issues can be minimized if startups allocate a suitable budget toward addressing these issues at early stages of business formation, employee hiring, vendor selection & retention, and so on.

Insurance

Obtaining an insurance policy covering IP-related infringement disputes may be worth considering. But whether this is worthwhile will depend upon the nature of the business.

One of the main benefits of having some form of applicable insurance coverage is that the policy may obligate the insurer to provide a defense. Given the potential high costs of IP litigation, this can be valuable. Also, an insurer’s involvement might help counteract infringement assertions of dubious merit, which are really nuisance-value lawsuits, by taking away the cudgel of the high cost of a legal defense.

Commercial general liability (CGL) business insurance policies frequently, but not always, include “advertising injury” protection in Coverage B—Personal and Advertising Injury. This may cover allegations of trademark and/or copyright infringement. Though sometimes one or both might be subject to an exclusion or endorsement that limits or even eliminates this type of coverage—policies vary. But even where there is coverage a typical policy will not protect against willful infringement and there may be relatively short windows when a claim must be formally filed with the insurer. If a CGL policy is not applicable or not adequate, specialized policies like media liability insurance can be considered.

However, patent infringement coverage is not included in typical commercial general liability insurance policies. Specialized patent infringement policies are available, but are rarely obtained by businesses. The cost of such a policy might be prohibitive for many startups.

It is worthwhile to scrutinize advertising injury or media liability coverage in insurance policies in the startup and early phases of a business. Seeking or negotiating the terms of such coverage may be significant if you are concerned about legal risks that might arise from your adoption of a new brand name or logo or through advertisements in print or online media—including social media. The benefits from such a policy can be significant if your business plans to run advertising or promote itself online (especially if using photos or other graphic-rich materials), or if it would be difficult or costly to later change your name, logo, or other branding.

Austen Zuege is an IP attorney and registered U.S. patent attorney practicing in Minneapolis. He has extensive experience with patents, trademarks, copyrights, domain name cybersquatting, IP agreements, and litigation.