Assignments of intellectual property (IP) such as for patents, trademarks, and copyrights are sometimes signed and then an error is later discovered. This is often due to a clerical or typographical error or other inadvertent mistake. For instance, there might be a typo in the number identifying a given patent, patent application, trademark registration, or trademark application in a schedule listing many. It is possible—and beneficial—to correct an assignment to fix such errors, which can then allow correction of any prior recordation of the original assignment. But how can such a correction properly be made? There are a few different possibilities, including using mark-ups or creating a new corrective document.

Marking-Up and Approving Corrections

One approach suggested by the U.S. Patent & Trademark Office (USPTO) (in MPEP 323 & 323.01(b) and TMEP 503.06(b)) and the U.S. Copyright Office (in Compendium 2308.1) for making corrections to an assignment is to have each of the parties conveying the property in question, that is, all of the assignor(s), make and approve corrections on the original signed assignment. This involves the following steps:

- Cross out the incorrect text or number (using strikethrough or a conventional proofreader’s delete/dele/deleatur mark through the text with a protruding loop)

- Write in the the correct text or number next to the crossed-out information (ideally immediately above it) using printed or typed lettering; use a caret mark or similar line or arrow to show the proper place of insertion, if helpful (a suggested practice if the only or best available space for newly inserted material is in a nearby area spaced from the crossed-out information, such as at a page margin)

- Have each and every assignor initial (or fully sign) and date the marked-up corrections; full signatures are also acceptable and are appropriate if multiple signatories have the same initials; if the assignee originally signed the document then the assignee should initial/sign and date the changes too

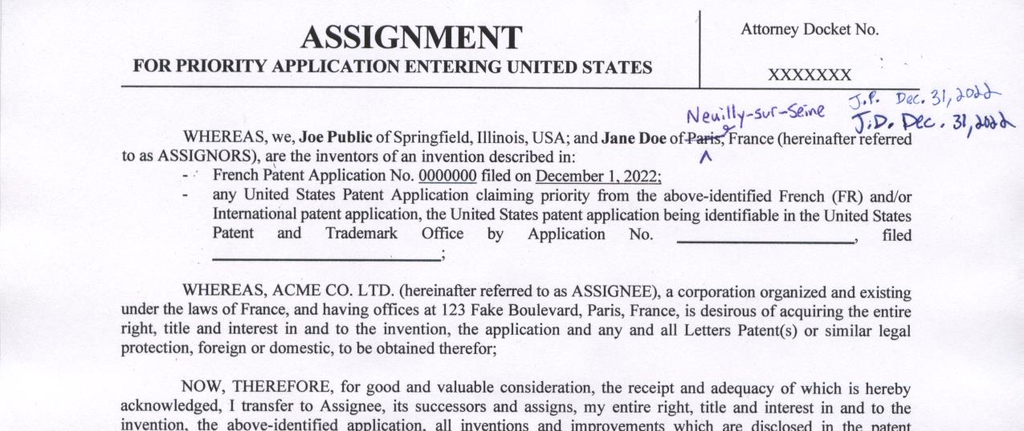

An example excerpt of a marked-up patent assignment document to correct an error on the original is provided below. In this example, the city of residence (Paris) of one inventor-assignor was incorrect and has been crossed out and the correct city name (Neuilly-sur-Seine) written immediately above it (using deleatur and caret proofreading symbols). Both of the two inventor-assignors (Joe Public/J.P. and Jane Doe/J.D.) have initialed and dated the marked-up change.

An advantage of marking up the original assignment is that doing so leaves no doubt that terms of the original assignment are still effective. The mark-ups make explicitly clear what specifically has been corrected. The adjacent initials/signatures and dates also clarify who approved the corrections and when. With the error in the original corrected, the chances that anyone might later cast doubt on the assignment due to that error are reduced or eliminated.

The retroactive (nunc pro tunc) effect of the corrections to the date of the original transfer of rights is inherent in the nature of marking-up and initialing/signing (and dating) changes on the original assignment document. This might be significant if something occurred between the time the original was signed and the time the error was discovered and corrected. For instance, if the original assignment with the error was already recorded, making marked-up corrections on the original facilitates recording the corrected document while making clear what specifically has changed.

The USPTO and the Copyright Office do not expunge or delete the previously recorded document, but instead further record corrected document(s) while noting that it is a corrective recordation. Although, uniquely, the Copyright Office will allow substitution of a corrected assignment within ten (10) business days of the original submission.

Keep in mind, however, that many aspects of assignments are a matter of state (or foreign) contract law, not USPTO or Copyright Office administrative procedure or even U.S. Federal patent, trademark, or copyright statutory law. Under black letter U.S. contract law, and presumably that of most other countries, it is not permitted to unilaterally modify or alter a contract after it has been signed. That may make the original voidable and may even be considered forgery, unless the assignment expressly permits a particular change (like later inserting application filing details). But having initials/signatures next to the changes from all the parties that originally signed the assignment removes doubt about their recognition of an error in the original and the fact that the correction/amendment was later made with their knowledge and approval. Although any material changes negatively affecting rights of the assignee or others will merit further attention, despite assignor approval.

However, if an error is identified in an assignment document before all parties have signed or provided notice to the assignee, it is usually preferable to discard the erroneous draft and provide a new copy with all the errors corrected for signature. Marked up corrections are not needed in that scenario, because the assignment with the error was not yet effective.

Newly-Created Corrective Assignment

Marking up and approving corrections to the original assignment is not those only way to correct errors. An alternative approach is to create a new corrective assignment document and have it signed by all the parties (meaning at least all the assignors). Federal agency guidebooks, in MPEP 323.01(b) (for patent assignments), TMEP 503.06(b) (for trademark assignments), and Compendium 2308.1 (for copyrights), recognize the possibility of such an approach for correcting previously-executed assignments.

For instance, if errors in a signed assignment are lengthy/voluminous, there is little available space to mark-up corrections, or the number of signatories does not leave enough space to add all their initials and dates, then a preparing and signing a new corrective assignment might be preferable to mark-ups. But if the original assignment containing the error was already recorded, or there has already been some reliance on that original assignment, any new “corrective” assignment may need its terms written to explicitly be retroactive to the effective date of the original. It is helpful if the title is identified as a “corrective” assignment too—although more than just the title should be changed. But the effort to create a new corrective document might be greater than using mark-ups.

A retroactive assignment is called a nunc pro tunc assignment, which is latin for “now for then”. These are widely used to correct errors in a prior assignment. The USPTO’s electronic assignment recordation systems EPAS and ETAS even have a special option for these, allowing the earlier date to be specified.

The USPTO describes a nunc pro tunc patent assignment recordation request as “[a] request to record an assignment, which includes documentation of transactions which occurred in the past but have not been made a matter of record in the USPTO.” This description implicitly treats nunc pro tunc patent assignment recordations as being (only) for corrective, confirmatory, or supplementary assignments. It means such a recordation request normally requires attaching additional documentation supporting the earlier claimed date of transfer or assignment (that is, the effective date prior to the execution date on which the new assignment document was fully signed).

The USPTO describes a nunc pro tunc trademark assignment as “an assignment that was prepared recently and is being recorded now, but the actual transfer occurred in the past. It is a complete transfer of ownership of trademark rights from the assignor/ (conveying party) to the assignee/ (receiving party). Use this conveyance type if the document being recorded was prepared after the time when ownership was actually transferred and after the time it should have been prepared and recorded, and has a retroactive effect. The execution date is usually later than when the actual transfer of ownership occurred.”

Lastly, if an error is identified in an assignment document before all parties have signed or provided notice to the assignee, it is usually preferable to discard the erroneous draft and provide a new copy with all the errors corrected for signature. A nunc pro tunc assignment or other explicit terms to provide a new, retroactive corrective assignment are not needed, because the assignment with the error was not yet effective.

Standing Limitations on Retroactive Patent Assignments

Corrective patent assignments, when necessary, should be completed before commencing a lawsuit for infringement. Courts generally do not allow nunc pro tunc patent assignments to provide retroactive standing to sue for infringement. The execution date on which a nunc pro tunc patent assignment was signed—or the date on which the last signature was obtained if multiple parties sign on different dates—is normally the effective date that controls for matters affecting standing. According to one district court, this also means that any subsequent assignments in a chain of title that were executed before a corrective nunc pro tunc assignment require further corrective action as well, because other purported assignments downstream in the chain were ineffective when executed (nemo dat quod non habet — one cannot give what one does not have). Clearing up chain-of-title issues before bringing suit allows the intended plaintiff(s) to be named, averting a possible ground for dismissal of the lawsuit due to the absence of a necessary party.

But not all nunc pro tunc assignments implicate standing. Minor corrections and supplemental terms may be given retroactive effect. At least one district court has held that correcting a drafting error in a prior assignment with respect to identification of a patent intended to be assigned did not deprive the assignee of standing in a pending lawsuit. And the Federal Circuit has held that retroactively adding the right to sue for pre-assignment infringement does not affect standing.

Practical Tip

There is an old saying that the best time to plant a tree was twenty years ago but the second best time is now. This provides a good analogy here. For assignments, the best way to correct them is to carefully check the information in them to fix any errors before they are presented for signature. In other words, be diligent and try to avoid errors from the start! That sometimes means verifying information provided by others, such as to ensure that legal names are used not nicknames or assumed names, corporations have not merged, dissolved, or changed names, addresses are current, etc. But the next best time to correct errors is as soon as they are discovered. Fortunately, there are ways to do that. Although doing so can become more difficult as time passes. For example, the original signatories can die, dissolve (if a corporation), or become uncooperative, and issues of standing can arise and later chain-of-title corrections might also become necessary that require additional corrective efforts.

Austen Zuege is an attorney at law and registered U.S. patent attorney in Minneapolis whose practice encompasses patents, trademarks, copyrights, domain name cybersquatting, IP agreements and licensing, freedom-to-operate studies, client counseling, and IP litigation. If you have patent, trademark, or other IP issues, he can help.