Patent law places the burden on the patentee to identify infringement and enforce the patent against infringers. This raises an important gating question. How can patent infringement be detected? Some patents—and more specifically some patent claims—can make detection of infringement either easier or more difficult. What follows are some important considerations about patent infringement detection, and a possible alternative to patenting for hard-to-detect inventions.

Proving Infringement

A patent establishes exclusive rights in an invention that provide a limited monopoly to the patentee. The claim(s) of a patent determine the scope of what is patented, and by implication what is not patented. There are different types of infringement possible under U.S. patent law. Each type has its own elements that must be proven.

Generally speaking, direct patent infringement in the U.S. requires that each and every element or limitation—as properly construed—of at least one claim of a patent is found either literally or (sometimes) equivalently in an accused product or method. The infringement analysis always involves comparing the asserted patent claim(s) to an accused product or method. Importantly, a patent only covers what is claimed. So the comparison for an infringement analysis always depends on what is (or is not) claimed. And literal infringement requires meeting each element of the claim exactly. Any deviation from a claim limitation (as properly construed) will preclude a finding of literal infringement.

Example Comparison for Infringement Analysis

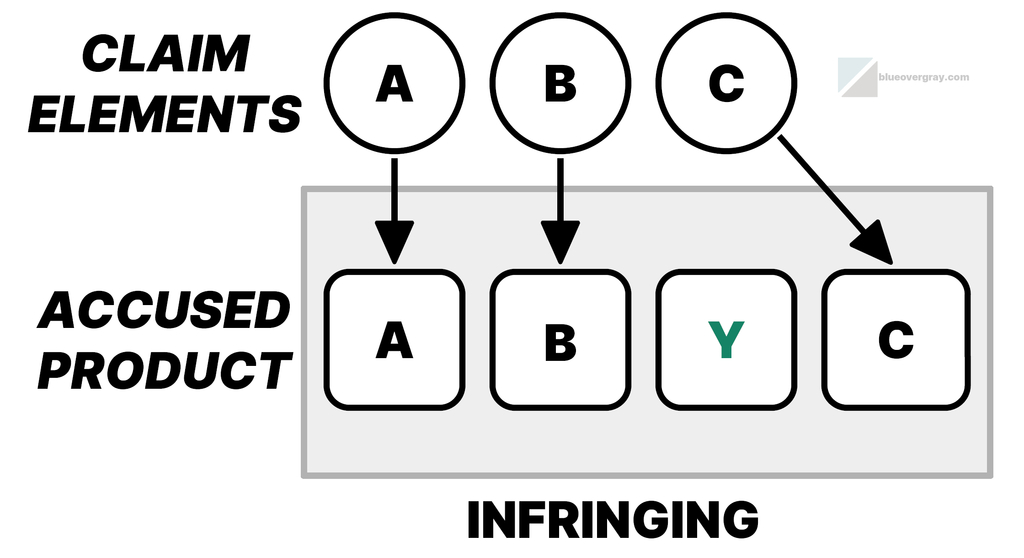

The following illustration helps explain how patent claims are compared to a potentially infringing product (or process). This example is highly simplified and assumes that the hypothetical claim has no negative limitations and no closed or partially-closed transitional phrases following the preamble, and that no Doctrine of Equivalents issues arise.

In the simplified example graphic above, a claim with elements A, B, and C is compared to an accused product. Here, the accused product contains each claim element A, B, and C. The accused product meets all the limitations of the claim, so there is infringement. Ordinarily, the presence of an additional element Y in the accused product does not change this result. The accused product does not have to be identical to embodiments disclosed in the patent. It only matters that the accused product falls within the scope of the given claim by meeting all of the claim limitations.

Alleging Infringement

In order to bring a lawsuit for infringement, there must be a reasonable basis to believe that infringement has occurred. Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 11 requires “an inquiry reasonable under the circumstances” before commencing a lawsuit. This encompasses both legal and factual aspects and bars complaints made for improper purposes (such as to harass). Courts can issue sanctions on attorneys, law firms, and parties for violations of this rule.

Courts have said that in patent cases Rule 11 requires, at a minimum, interpreting the asserted patent claim(s) in a non-frivolous manner and comparing the accused device with those claims before alleging infringement. See Q-Pharma, Inc. v. Andrew Jergens Co., 360 F.3d 1295, 1300-03 (Fed. Cir. 2004).

“In bringing a claim of infringement, the patent holder, if challenged, must be prepared to demonstrate to both the court and the alleged infringer exactly why it believed before filing the claim that it had a reasonable chance of proving infringement. Failure to do so should ordinarily result in the district court expressing its broad discretion in favor of Rule 11 sanctions . . . .”

View Eng’g, Inc. v. Robotic Vision Sys., Inc., 208 F.3d 981, 986 (Fed. Cir. 2000)

So it is not permitted to simply wildly guess or casually speculate that an accused product meets all the limitations of a patent claim. But applicable rules means that judges ultimately decide what is reasonable or non-frivolous under the circumstances.

Detectability

Establishing infringement means proving that all the elements of an asserted claim are present. And bringing a lawsuit in the first place requires reasonable confidence you will prevail. But what if you can’t tell exactly how a potentially infringing product is configured or how it was made or operates during use? For instance, what if there are inaccessible internal components, the composition of certain materials cannot be tested, manufacturing methods are not apparent from resulting physical characteristics, or the performance of certain software-based computer processing steps is unclear? Or what if a method of use requires that an end user operate a device but it is unknown if or when that has happened? These are all problems with detecting infringement.

The crux of the detectability issue is that you need to have a level of information about potentially infringing products commensurate with the level of detail recited in the claim(s) of a patent. Investigations to locate that information can range from the simple to the complex and expensive to the impossible. Sometimes merely reviewing marketing materials for competing products is insufficient to understand if claimed elements are present or not. Then it may be necessary to obtain one of the products for evaluation, or look for some other source of the missing information.

However, U.S. patent law provides a possible presumption of infringement by a product alleged to be made by a patented process. Qualifying for that presumption requires that (1) there is a substantial likelihood that the product was made by the patented process and (2) there was a reasonable but unsuccessful effort to determine the process actually used in production. (35 U.S.C. § 295). Yet this presumption is only applicable to patented methods of manufacturing, not methods of use, for instance.

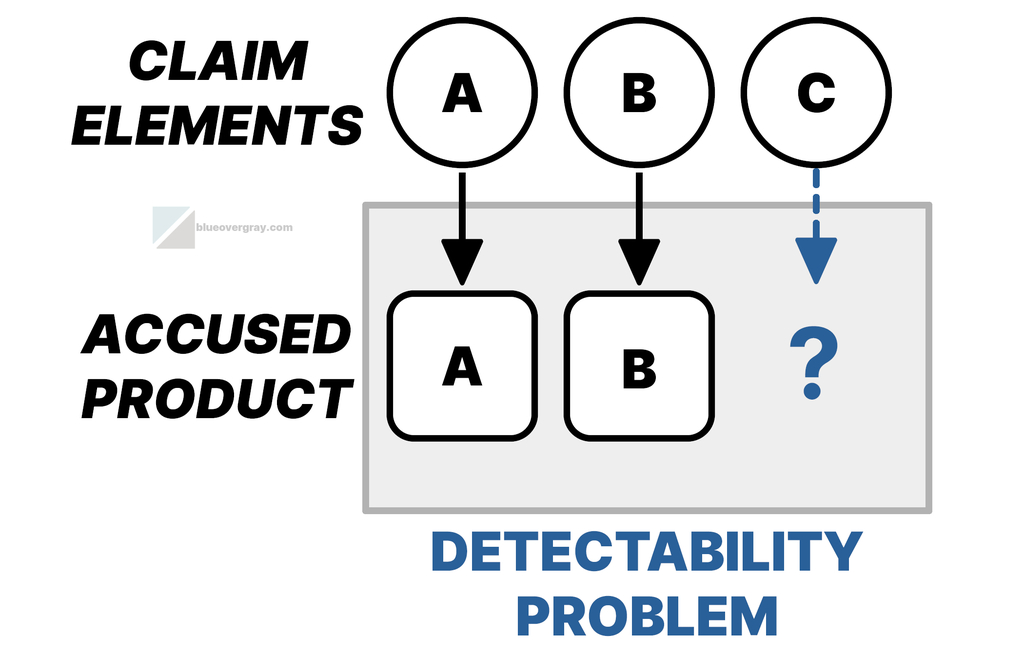

Example Detectability Problems

In the simplified example graphic immediately below, another accused product is compared to the claim with elements A, B, and C. This accused product meets claim element A and B. However, it is unclear whether claim element C is found in the accused product or not. This is a detectability problem. Whether infringement has occurred or not here is not yet known because it has not yet been established that the accused product falls within the claim. More information about the accused product is required to make a final determination.

Take as another example a patented software-driven device that produces a particular result based on a certain type of calculation (following a specific algorithm). If it is possible for competing products to achieve the same result using different calculations, then it may be hard to detect infringement. It may not even be possible to reverse-engineer how particular software commands are written. In this situation, detection of infringement may be difficult even if all the physical hardware components are the same.

Yet another example involves a claim to a chemical with a particular molecular structure. You must have the means to test for the presence of that molecular structure to detect infringement. This might necessitate obtaining product samples and sending them to a lab for analysis.

Patentability and Detection

Ideally patent claims will only recite elements that are easily detected through convenient forms of inspection or testing of an accused product. This aids with enforcement of the patent. During patent preparation and prosecution, care should be taken to write claims that recite what is detectable rather than what is not. Although, this is sometimes more easily said than done.

Before enforcing a patent you first have to obtain a patent. This means convincing at least one patent examiner that the claimed invention is patentable. The broader the claim, the more difficult it can be to establish patentability. It is fairly easy to want broad claims. What patentee wouldn’t want wider coverage? But you can’t always get what you want. Sometimes difficult- or impossible-to-detect elements are precisely what make inventions patentable over the prior art. Without them, the claims may be rejected as unpatentable. In those situations, the choice may be between claims that make it hard to detect infringement or having no patent at all.

Trade Secrecy as an Alternative to Patenting

There is an alternative to patenting. And that is trade secrecy. Of course, not all inventions lend themselves to being kept secret. But an invention that is not detectable in physical products, or only involves steps performed away from public view, may be a good candidate for trade secrecy. An example is a manufacturing method, or a machine, tool, or fixture used in manufacturing. These sorts of things can often be keep secret inside a private factory. Another example is a “secret formula” for a chemical composition that cannot be reverse-engineered through testing. So an inventor may have a choice between either pursuing a patent or instead maintaining a non-detectable invention as a trade secret.

An important consideration when relying on secrecy is the level of confidence you can have that it is practical to do so. Trade secret protections are lost when something is publicly disclosed. So foregoing patent protection means thinking long and hard about what steps can be taken to maintain secrecy and how effective those steps are likely to be.

Austen Zuege is an attorney at law and registered U.S. patent attorney in Minneapolis whose practice encompasses patents, trademarks, copyrights, domain name cybersquatting, IP agreements and licensing, freedom-to-operate studies, client counseling, and IP litigation. If you have patent, trademark, or other IP issues, he can help.