Important Developments

As 2024 begins, some recent and upcoming changes in practice at the U.S. Patent & Trademark Office (USPTO) for patent and trademark matters and at the U.S. Copyright Office for copyright matters merit attention, along with developments from U.S. courts pertaining to those areas of intellectual property (IP) law. (Click the preceding links to jump to desired content).

Patents

Non-DOCX filing format requirements postponed (yet again)

The deeply unpopular surcharge for U.S. non-provisional utility patent applications in a non-DOCX file format has been postponed yet again, until January 17, 2024. Although even when in effect this surcharge will not apply to PCT national phase entries, provisional applications, plant applications, or design applications. Furthermore, the USPTO has indefinitely extended a highly limited opportunity to file a back-up applicant-generated “Auxiliary PDF” version of an application filed in DOCX format, in order to potentially allow for later correction of USPTO-side conversion errors involving the DOCX version. These postponements and extensions are the result of many strong objections from U.S. patent practitioners and practitioner organizations.

It remains to be seen whether there will be further postponements or a larger change in USPTO policy about mandatory DOCX filings, which in general provides only a small clerical benefit to the USPTO while placing large burdens and costs on applicants.

Guidance for creating application documents (hopefully) compliant for USPTO DOCX filing is available here. But applicants with complex application content should consider the possibility of paying the non-DOCX official surcharge and filing applications in PDF format to avoid the risks associated with USPTO-generated errors in substantive application content.

Electronic patent “eGrants” now in place

On April 18, 2023, the USPTO began issuing an electronic PDF copies of patent “eGrants” as the official versions of granted patents. Continuing a long tradition, patent eGrants are issued on Tuesdays. As of December 2023, “ceremonial” paper copies were still being automatically sent as part of a transition period. The end date of that transition period, when paper copies will no longer be sent, has not been specified. Whenever the transition period does end, paper copies of patents can still be ordered from the USPTO for a small official fee (currently $25). However, ordered copies will either be a certified copy of the entire patent (which lacks the decorative color cover like eGrants and instead includes a certification cover page) or a “presentation” patent (which is a partial certified copy of only the front page of the patent, with a unique certification statement and special seal). Both of those differ from current “ceremonial” copies.

Of note, any color drawings in patents do appear in color in the new electronic patent eGrants. This potentially reduces the need to specially order color copies.

Further, the USPTO will also begin issuing certificates of correction electronically starting January 30, 2024. Paper hard copies of certificates of correction will not be mailed after that date, although they can still be specifically requested for a fee like other patent documents.

Massive official fee increases proposed, but implementation unclear

In April of 2023, the USPTO announced plans for significant official fee increases. Materials related to those efforts can be found here, including an Executive Summary of the key official patent fee increases proposed. If implemented, many fees would be increased by 25% and some by over 700%! And some wholly new fees are proposed. The Executive Summary should be consulted for more details because of the sweeping extent of the proposed fee schedule changes.

For example, the USPTO has proposed tiered fees for continuing applications (with large fees required if a continuing application is filed more than three or seven years after earliest parent’s filing date), new fees if the number of citations submitted with information disclosure statements (IDSs) exceed tiered thresholds, higher excess claim fees, more steeply increasing subsequent request for continued examination (RCE) fees, new fees for After-Final Consideration Pilot (AFCP) 2.0 requests, reinstating and increasing fees for assignment recordations submitted electronically, and enormous increases in design application fees. The design application fee increases are being driven by the prevalence of mostly foreign applicants filing expedited examination requests as micro entities, which has created a large backlog of non-expedited design applications.

While the USPTO currently has fee-setting authority “only to recover the aggregate estimated costs to the Office,” many of the proposals would appear to exceed that authority to try to shift or discourage certain actions by applicants.

At present, the USPTO has not made further announcements in response to comments about its patent fee proposals. Some changes to the initial proposals are certainly possible. But extremely large official patent fee increases are likely by January 2025. More official information should be available sometime in the first quarter of 2024.

Design patent 1 million issued and design patent bar created

In 2023 the USPTO issued design patent 1,000,000. Also, the USPTO authorized a design patent-specific bar for practitioners without scientific or engineering backgrounds to prosecute design cases. This new design patent bar does not restrict the ability of other patent practitioners to handle design applications. Regular patent practitioners with scientific or engineering backgrounds are still able to handle any and all types of patent applications, for utility, design, or plant matters. But practitioners admitted to the new design patent bar will not be able to handle utility or plant patent applications. Other developments in the courts related to design patent practice are discussed below.

Suggested figure for publication policy changed

Applicants were previously able to suggest a figure to appear on the front page of a pre-grant publication of a patent application, but the USPTO independently decided which figure to publish on the front page and sometimes chose a different one. That policy has changed. The USPTO now exclusively uses the drawing figure suggested by the applicant for the front page of the pre-grant publication when that suggestion is included on a compliant application data sheet (ADS) that is timely filed before the USPTO begins its process of publishing the application. Despite this change, it is still common (and often recommended) for applicants to allow the USPTO to select a figure for publication on the front page and not suggest one.

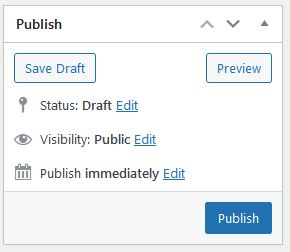

Changes to USPTO online systems

On November 15, 2023, the USPTO permanently retired its PAIR and EFS-Web systems. This leaves only the USPTO’s Patent Center for making electronic filings and retrieving file histories. Although the USPTO has said that Patent Center provides all the functionality of the retired systems, that is not accurate. For instance, without any formal announcement, the USPTO deactivated its First Office Action Estimator tool. In truth, that estimator tool had ceased to be accurate for some time. But applicants are now left with no mechanism to estimate the time until substantive examination begins. Patent Center has reduced functionality in numerous areas and practitioners have found it to be prone to bugs and usability problems, including a lack of capacity.

The USPTO has also announced a plan to “reform” the Electronic Trademark Assignment System (ETAS) and the Electronic Patent Assignment System (EPAS) into one cohesive and modernized system called the Intellectual Property Assignment System (IPAS). IPAS is slated to be available starting January 15, 2024 [UPDATE: the transition date was pushed back to February 5, 2024]. No further details are available at this time, so it is unclear how the new assignment system will differ or what the apparently integrated patent and trademark recordation interface will look like.

More U.S. patent filing information

Please also see the Guide to Foreign Priority Patent Filings in the USA for in-depth discussion of requirements for foreign applicants to file U.S. counterpart patent applications with a foreign priority claim. Additional basic information about patenting can be found in the Patent Basics guide.

Trademarks

Fee increases proposed

In May of 2023, the USPTO announced plans for official trademark fee increases. Materials related to those efforts can be found here, including an Executive Summary of the key official trademark fee increases proposed. If implemented, the naming convention and types of fees would change. For example, a typical trademark application would see at least a $100 fee increase. And, if custom identifications of goods/services are used rather than merely selecting ones from pre-approved descriptions from the Trademark ID Manual, then new “premium” surcharges of $200 per class would apply. This means that many (if not most) new trademark applications will see official filing fees increase by at least $300, and possibly more if there are multiple classes of goods/services. Somewhat similar fee structure changes and official fee increases would apply to Madrid Protocol extensions to the USA too. Various other fees will increase 10-66% or more, including a 400% increase in the fee for a letter of protest, for example.

At present, the USPTO has not made further announcements in response to comments about its trademark fee proposals. Some changes to the proposals might be made, but significant official increases are a certainty. More information should be available from the USPTO in the first quarter of 2024, and the new fees are expected to go into effect by November 2024.

New trademark search and assignment recordation tools

The USPTO retired its Trademark Electronic Search System (TESS) on November 20, 2023. A new Trademark Search tool has been made available in its place. The new tool has a more modern-looking interface. It still includes search functionality similar to that of TESS, but no longer times out during searches. Also, it offers the ability to export search results and other information as a spreadsheet. However, the USPTO has warned that the new Trademark Search system will sometimes display outdated status information, drawn from a Trademark Reporting And Monitoring (TRAM) system that the USPTO plans to retire sometime in 2024. The most accurate trademark status information can be found instead in the USPTO’s Trademark Status and Document Retrieval (TSDR) system, which is linked in individual search results. Training materials on how to use the new Trademark Search tool are available.

As noted above regarding patent developments, a new trademark (and patent) assignment recordation system called the Intellectual Property Assignment System (IPAS) is slated to become available starting January 15, 2024 [UPDATE: the transition date was pushed back to February 5, 2024].

More U.S. trademark filing information

Please also see the Guide to Trademark Registration in the USA for in-depth discussion of requirements for foreign applicants to file U.S. federal trademark applications. Additional basic information about trademarks can be found in the Trademark Basics guide.

Copyrights

AI-generated works usually not copyrightable

The U.S. Copyright Office requires that works be authored by a human to be copyrightable. In the generative AI context, authorship requirements begin by asking whether the work is basically one of human authorship, with the computer/AI merely being an assisting instrument, or whether the traditional elements of authorship in the work (literary, artistic, or musical expression or elements of selection, arrangement, etc.) were actually conceived and executed not by a human but by a machine. The Copyright Office takes the view that when an AI tool solely receives a prompt from a human and produces complex written, visual, or musical works in response, such prompts function like instructions to a commissioned artist and the person making the prompts is not considered an author. Accordingly, in that situation the resultant AI-generated work is not protectable by copyright. On the other hand, if AI-generated elements are further selected and arranged by a human, those aspects may be protectable, with the non-copyrightable AI-generated elements disclaimed.

In copyright registration applications, applicants have a duty to disclose the inclusion of AI-generated content and to provide a brief explanation of the human author’s contributions to the work. Given the interest in this area, the Copyright Office has an ongoing initiative and inquiry. Applicable policies and legal standards may continue to evolve.

Significant Developments in U.S. Courts

Patent enablement requirements reinforced

The U.S. Supreme Court unanimously ruled in Amgen v. Sanofi that “[i]f a patent claims an entire class of processes, machines, manufactures, or compositions of matter, the patent’s specification must enable a person skilled in the art to make and use the entire class. In other words, the specification must enable the full scope of the invention as defined by its claims. The more one claims, the more one must enable.” This important decision reaffirmed a principle set out in cases going back more than a century, which preclude the grant of a patent monopoly extending beyond the invention actually disclosed. In this way, a central underlying premise of modern patent law was confirmed, that of a quid pro quo or “bargain” between the inventor(s) disclosing the invention and the public granting a limited monopoly in exchange. The Court discussed famous historic cases, including those involving Samuel Morse and Thomas Edison, as setting out the same enablement requirements.

In the Amgen case, in particular, the central issue revolved around the use of functional claim language that encompassed an entire genus of embodiments of antibodies coupled with the disclosure of inadequate teachings and embodiments pertaining to only a subset of species within that genus. The patentee Amgen had disclosed only a few (26) working examples plus a roadmap for a trial-and-error process that would have involved undue, “painstaking” experimentation to arrive at the entire claimed genus (encompassing at least millions of candidates). This was found inadequate and so the invalidation of the relevant claims for lack of enablement (under 35 U.S.C. § 112(a)) was affirmed.

A specification may call for a reasonable amount of experimentation to make and use a patented invention. Often that can be done by disclosing a general quality or general rule that may reliably enable a person skilled in the art to make and use all of what is claimed (and not merely a subset). But what is reasonable in any case will depend on the nature of the invention and the underlying art. Although not explicitly discussed in the Amgen case, courts have long recognized a distinction between so-called “predictable” arts like those involving mechanical and/or electrical inventions and “unpredictable” arts like those involving chemical and biotech inventions, as well as the amount of knowledge in the state of the art available to a person of ordinary skill. The more predictable the art, and the more knowledge a person of ordinary skill in the art would have, the less disclosure is required for enablement. Although even in the “predictable” arts enablement issues can arise, especially where “preemptive” functional or result-only claim language is used.

[Edit: in January 2024, the USPTO released guidance regarding the enablement requirement for utility patent applications in view of Amgen v. Sanofi. Existing USPTO practice of following the so-called Wands factors were essentially reaffirmed.]

Treatment of design patents continues to change

U.S. design patent practice has seen a number of significant shifts and important court decisions in recent years. Notably, there is currently a case called LKQ Corp v. GM Global Tech. Operations LLC pending rehearing that will clarify obviousness standards for designs, and how that standard is the same or different from obviousness for utility patents. At stake is whether design patents will be treated uniquely, with essentially a lower threshold for patentability (currently, obviousness is more difficult to establish for designs), or subject to basically the same non-obviousness standard as for utility patents.

Another controversial decision in the Columbia II case limited the use of “comparison” prior art in infringement analysis to highlight similarities or differences between the patented design and the accused product that might not otherwise be apparent to an ordinary observer. That case built upon recent emphasis on the title of design patents being limiting, and expanded on a prior case (In re Surgisil) that said only prior art pertaining to the same type of article claimed can be used for patentability analysis, even though prior precedential cases had said that considerations about use of an article are immaterial. The main takeaway is that the law around design patents continues to shift, and at least some judges have attempted to expand or strengthen design patentees’ power in ways that seem to depart from binding precedent.

District of Delaware holds patent case plaintiffs accountable

Chief District Judge Colm Connolly of the District of Delaware has implemented a standing order requiring disclosure of third-party litigation funding. This policy differs from some other districts (and other judges) that refuse to require such disclosures, even in response to discovery requests. These disclosure requirements help to identify real parties in interest to allow for recusal of the judge if a conflict of interest arises due to the judge having an ownership interest in the litigation funder.

In a set of patent cases brought by non-practicing entities believed to be connected to a common litigation funder, Chief Judge Connolly has issued sanctions and referred attorneys and a party to criminal prosecutors and state bars responsible for attorney licensing. These stem from allegations that the litigation funder is directing the litigation and attorneys are taking instructions from entities other than the named party in the lawsuit, which may constituent the unauthorized practice of law and/or a breach of attorney ethical obligations.

In at least one other case, these policies have also led to dismissal where litigation funder confidentiality agreements have precluded compliance with the Chief Judge’s funding disclosure requirements.

The significance of these probes and disclosure requirements is that these patent lawsuits are generally brought by corporate entities formed only for the purpose of bringing a patent lawsuit, and which have essentially no assets. The lack of assets by a shell company is used by litigation funders to try to shield themselves from liability for possible sanctions and attorney fee awards for bringing meritless or objectively baseless lawsuits. Occasionally, similar cases have involved accusations of sham assignments, which can impact the standing of the plaintiff to bring suit if ownership rights are illusory. These policies also bolster and supplement corporate disclosure requirements under Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 7.1, which on its face does not address things like contractual obligations that can curb settlement power or incentives, or when an entity has the power to control another through “negative control” or economic dependence standards applied by the U.S. Small business Administration to determine “affiliate” status and in turn to determine USPTO entity size status.

More generally, Chief Judge Connoly’s policies present some long-overdue limits on the use of courts to extract nuisance settlements, a problem that has been well-documented with respect to so-called “patent trolls”.

Prosecution laches

Certain cases have continued to apply so-called “prosecution laches” to render patents unenforceable. Prosecution laches is premised on prejudice to an accused infringer by the patentee’s unreasonable and inexcusable delay in prosecution of the asserted patent. Cases that apply this doctrine typically involve continuing applications. Recently, this doctrine has been applied in prominent cases by independent inventor patentees. These cases merit attention for a number of reasons. The criticized “egregious misuse” of the patent system is not something confined to a few isolated instances, but is rather commonplace. For instance, similar conduct in creating patent thickets with multiple continuation applications is routine in medical device patenting. And it is not uncommon for patentees to write claims in continuing applications to cover competitor products. Most significantly, the application of a laches defense is in tension with the Supreme Court’s 2017 SCA Hygiene decision saying that laches cannot be invoked as a defense against a claim for damages brought within the six-year limitations period of 35 U.S.C. § 286. The crucial issue is whether (or when) a judge-made policy can preclude use of statutory provisions allowing continuing applications. Also notable is reliance on unenforceability rather than, for instance, invalidity based on lack of enablement—many continuing applications of the sort that raise these questions would seem to be vulnerable to allegations of lack of enablement in the original disclosure, which is a statutory requirement.

Double patenting and patent term adjustment

In the In re Cellect case, the Federal Circuit held that patent term adjustment that differeed among patents in a family led to invalidity for obviousness-type double patenting, because the patents did not expire on the same date. This case is notable because it held that the judicially-created doctrine of double patenting led to unpatentability as a result of USPTO delay, despite the fact that this stemmed from a statutory provision (35 U.S.C. § 154) granting patent term adjustment. In other words, it presents a significant judicial/legislative separation of powers issue. On the other hand, double patenting concerns only arise when a patentee chooses to file multiple patent applications with overlapping scope.

Normally, double patenting can be overcome by filing a terminal disclaimer. But the In re Cellect case presented an unusual situation. It involved a reexamination of an already-expired patent, and terminal disclaimers are not permitted for expired patents. However, the decision in that case still established that a patent can be invalidated or found unpatentable as a result of USPTO delay, thus requiring terminal disclaimers in more situations than was generally believed necessary previously.

Copyright mandatory deposits found unconstitutional

The Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit has ruled in the Valancourt Books v. Garland case that the mandatory deposit requirement of the copyright laws (17 U.S.C. § 407) is unconstitutional under the Takings Clause of the Fifth Amendment of the Constitution. Mandatory deposits provided copies of works for archiving by the Library of Congress. Although some form of mandatory deposit requirement has been in place since the first copyright law was passed in 1790. But the D.C. Circuit ruled that subsequent amendments to the copyright laws had left mandatory deposits “untethered” from the benefits of copyright registration, rendering them a government taking without compensation prohibited by the Constitution. Penalties for failing to make a mandatory deposit will no longer apply.

Fair use eviscerated by Supreme Court

In a pair of rather shocking decisions (Jack Daniel’s and Andy Warhol Foundation), the U.S. Supreme Court has greatly limited “fair use” defenses with respect to both trademarks and copyrights. These decisions greatly reduce freedom to operate based on parody or artistic transformation defenses that were largely taken for granted for a long time under U.S. law, and reflect unconvincing treatment, if not outright disregard, for both fact and law. A return to prior treatment of fair use will apparently require legislative action, which is not likely in the near future.

Role of fraud in trademark matters

In the Great Concepts v. Chutter decision, the Federal Circuit held that fraud in a declaration of incontestability (under § 15 of the Lanham Act, 15 U.S.C. § 1065) cannot be used as a ground to cancel a trademark registration. This creates a split with the Ninth Circuit’s prior 1990 decision in Robi v. Five Platters, which held that a statement of incontestability that fraudulently asserted that there were no adverse decisions involving the registered mark justified cancellation. This means that this particular ground for challenging a registration will only be available in courts and not in Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (TTAB) administrative cancellation proceedings.

Significantly, the Federal Circuit did not reach a major point from the appealed TTAB Great Concepts decision holding that recklessness was sufficient to establish fraud. The Federal Circuit has generally taken an idiosyncratic view of fraud, and numerous past decisions (not limited to trademark law) have made it difficult to prove fraud—despite (or rather because of) the prevalence of accusations and circumstantial evidence of fraud. This issue is also loosely tied to the contentious Iqbal/Twombly “plausibility” pleading standards, which altered longstanding notice pleading requirements, and which research has shown allows judges to limit access to the courts (and associated evidentiary discovery) for certain types of claims for ideological reasons.

Crisis of legitimacy in judiciary continues

U.S. Supreme Court justices have been mired in ethics scandals and public confidence in the Court remains at or near record lows. These scandals have revolved around essentially influence/bribery concerns and deficient disclosure of income and “gifts” that call into question judicial impartiality. There was a recent introduction of a code of conduct formulated by the Supreme Court justices themselves with no clear enforcement mechanism—with the justices apparently taking the position that they have already been compliant with the new code of conduct, as an attempt to deflect the serious charges leveled against them rather than meaningfully address them. The judiciary’s self-policing has been criticized in general.

Specifically in the IP field, on September 20, 2023 Judge Pauline Newman was suspended for one year from the Federal Circuit, the court with exclusive appellate jurisdiction over patent lawsuits. At 96 years old, she is the oldest current serving U.S. federal judge, appointed by President Regan in 1984. Her suspension resulted from her refusal to cooperate with an investigation into her fitness due to health issues and her treatment of court staff. As of December 2023, she has still refused to either retire or cooperate with the official investigation, a course of conduct that has reflected poorly on her and, more broadly, has tarnished the reputation of the judiciary as a whole. Judge Newman continues to challenge her suspension and the investigation as a whole—on “libertarian” grounds that deny government authority and therefore sit uncomfortably with her role as a federal judge.

Additionally, an employment-related complaint by an administrative patent judge (APJ) at the USPTO for abuse of authority was initially sustained in May of 2023. The APJ had reported interference with Patent Trial & Appeal Board (PTAB) judge assignments through “panel stacking” in order to alter case outcomes (in a separate Freedom of Information Act [FOIA] case, the USPTO refused to disclose how often this occurred). Supervisors then retaliated against him. This matter points to more general transparency and credibility problems and a lack of independence of administrative judges (within the executive branch). It follows a 2022 Government Accountability Office report finding that a majority (67%) of APJs felt pressured by management to alter specific decisions in AIA proceedings and a smaller but still significant number (34%) felt similar pressure in ex parte appeals. It further follows the Supreme Court’s 2021 Arthrex decision, which held that APJ appointments violated the Appointments Clause of the Constitution but that such deficiencies were resolved by allowing PTAB decisions to be reviewed by the Director of the USPTO—essentially undermining APJ independence and objectivity in favor of protecting the political aspects of appointment authority. These issues also recall concerns about secret USPTO actions during application examination placing public relations / perception management concerns ahead of objective patentability requirements established by the legislature.

To foreign observers, the crisis of legitimacy in the U.S. judiciary might seem to merely extend a legitimacy problem with U.S. government action both domestic and worldwide, including investigations/proceedings against presidents past and present and conduct before bodies like the United Nations.

December 2023

Austen Zuege is an attorney at law and registered U.S. patent attorney in Minneapolis whose practice encompasses patents, trademarks, copyrights, domain name cybersquatting, IP agreements and licensing, freedom-to-operate studies, client counseling, and IP litigation. If you have patent, trademark, or other IP issues, he can help.