The U.S. Patent & Trademark Office (USPTO) requires that non-provisional patent applications filed on or after January 17, 2024 be submitted electronically in Office Open XML “DOCX” file format in order to avoid a non-DOCX official surcharge. This means applications can still be filed electronically in PDF format, or by paper, but doing so will require payment of an additional official fee that varies according to the applicant’s entity size (initially $400/$160/$80 for large/small/micro entities).

What Types of Applications Must be in DOCX Format?

The DOCX filing requirement and non-DOCX surcharge currently applies only to the following U.S. patent applications:

- Utility patent applications (non-provisional) under 35 U.S.C. § 111(a)

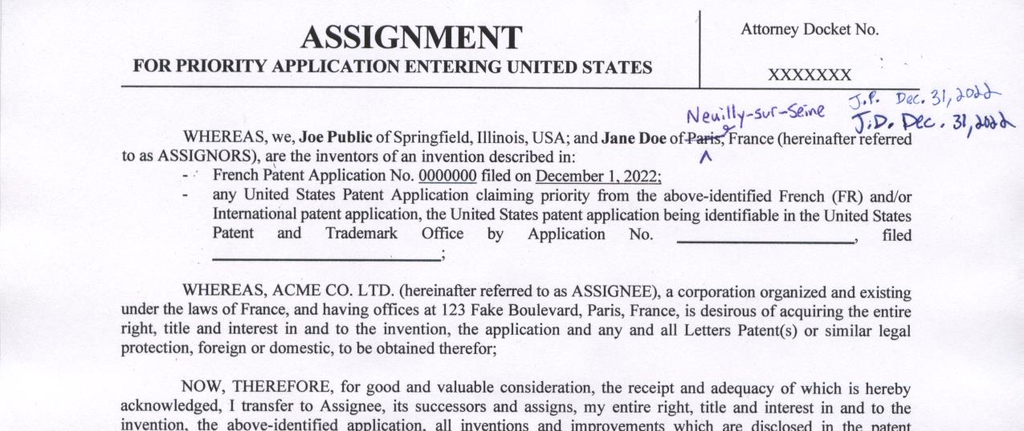

- Includes direct U.S. filings with a Paris Convention foreign priority claim

- Includes PCT “bypass” applications

However, the non-DOCX surcharge currently does not apply to the following types of U.S. patent applications:

- Provisional patent applications

- Design patent applications

- Plant patent applications

- PCT national phase entries

Additionally, only certain portions of an application are covered by these requirements. In order to avoid the non-DOCX surcharge, the specification/description, claims, and abstract must all be in a compliant DOCX format. However, the drawings of an application do not need to be submitted in DOCX format. PDF format can be used for electronic submissions of figures without paying a non-DOCX surcharge.

In an answer to a frequently asked question (FAQ), the USPTO has said that the non-DOCX surcharge applies to U.S. applications filed in a language other than English under 37 C.F.R. § 1.52(d)(1). That is, avoiding the surcharge requires filing a DOCX copy of the non-English original. This approach was not officially announced prior to implementation of the surcharge. Of course, that position is at odds with the USPTO’s justification for implementing the non-DOCX surcharge in the first place, because only the English translation is published.

Potential Problems

When application documents are electronically filed with the USPTO’s Patent Center system in DOCX format, they are “validated” to create a new DOCX file and also converted into another format (PDF) by the USPTO with a proprietary conversion/rendering engine prior to submission. For instance, tracked changes strikethrough and underlining/underscore formatting are automatically removed as part of file “validation”. However, that “validation” and conversion process can produce errors. Yet it is the “validated” DOCX file as modified by the USPTO’s system that is considered the “as filed” version that the USPTO actually relies upon for subsequent actions, and not the DOCX file as originally uploaded. The original applicant-created DOCX file is discarded by the USPTO as part of the “validation” process, meaning the USPTO does not preserve the original source file in unaltered (pre-validation) form. Underlying these concerns is the fact that DOCX format is not platform-stable, and rendering of a given document varies depending on the configuration of the computer that opens it. These aspects of DOCX filing are the major sources of concern.

Experience to date has shown that USPTO-side DOCX conversion error issues are particularly significant for application documents involving:

- Embedded mathematical equations created with a word processing program’s built-in equation editing functionality

- Embedded chemical formulas created with a word processing program’s built-in formula editing functionality

- Pseudo computer code with special indenting having technical meaning or special significance

- Data tables, particularly if the table introduces landscape page orientation that varies from other pages with portrait orientation or if there is complex table formatting with special formatting like substantively meaningful indenting within table cells

- Text in unusual characters/symbols or fonts, including Greek letters and/or uncommon accent marks with technical significance

- Claim autonumbering using automatic numbered list formatting

- Document creation using a word processing program other than a version of Microsoft Word® using a Latin-alphabet interface

- Document creation or editing with word processing program plug-ins or macros for machine translations, automatic application content population, and the like, especially when such plug-ins lock application formatting or content against further editing

Many of these things are fairly common in patent applications.

The USPTO treats a DOCX version as the definitive record copy, potentially allowing later correction of USPTO-side conversion errors by filing a petition. However, the USPTO has clarified that only the “validated” DOCX file as modified by the USPTO’s systems during the filing process are treated as authoritative and not the applicant’s pre-“validation” source version. The USPTO has also said that petitions requesting a correction more than one year after a DOCX submission will not ordinarily be granted (except that, if applicable, incorporation by reference of a priority application or filing a pre-English-translation version may provide a different, independent basis to request correction more than a year later). This time limit stemmed from the USPTO saying it may discard applicant submissions after one year, retaining only a USPTO-converted/validated file — although a later USPTO rule announcement indicated that applicant-generate PDFs will now be maintained as part of the permanent record and not discarded. There remain some ambiguities and inconsistencies in these USPTO statements, particularly because the USPTO never specifically retracted its statement that petitions filed more than one year after an application is filed will not ordinarily be granted.

The USPTO has permitted a limited opportunity to file a back-up applicant-generated PDF version (“Auxiliary PDF”) of an application filed in DOCX format that can further allow for later correction of USPTO-side conversion errors. However, this Auxiliary PDF submission is being permitted indefinitely, during which time there are no extra official fees associated with submitting an Auxiliary PDF or to petition to correct a USPTO-side conversion error based on such an Auxiliary PDF. And the USPTO has said that the Auxiliary PDF will be retained as part of the permanent record for a given application. However, there is significant effort (and associated time cost) required for an applicant to prepare and file a petition to correct a USPTO error, and there is no guarantee that such a petition will be granted. Indeed, some petitions to correct USPTO-side DOCX conversion errors have been denied and/or have significantly delayed examination.

Another very significant point is that the USPTO has taken the position (first stated in a FAQ answer published only after the surcharge went into effect, then further clarified in a notice in May of 2024) that a preliminary amendment filed on the same day as an application subject to the DOCX requirement must also be in DOCX format. Failing to file the preliminary amendment on the same day as the new application means it will not be treated as part of the original application. This places additional burdens on applicants. For one, it was not until November 13, 2024 that the USPTO’s Patent Center electronic filing system permitted DOCX format preliminary amendments to be filed simultaneously with a new application (!). When doing so, an “Auxiliary PDF” can be submitted that combines the PDF of the original application and the PDF of the preliminary amendment. However, the USPTO has not provided any guidance about its treatment of substitute specifications in DOCX format, and therefore the ability to file those while avoiding the non-DOCX surcharge remains unclear and prone to risks for applicants. Also, the USPTO had for a long time informed practitioners that DOCX amendment filings in Patent Center did not work properly and should be avoided. One reason was that DOCX-format files with “tracked changes” to show amendment mark-ups would be entered thus removing the mark-up indications when submitted to the USPTO. However, as some unspecified time during 2024, and without any prominent announcement, the USPTO changed the functionality of Patent Center such that “tracked changes” mark-ups in DOCX-format files are converted into fixed-formatting underlining and strikethrough. Whether that conversion/rendering process at the USPTO side works properly or produces errors is difficult and burdensome to verify. Therefore, by imposing a non-DOCX surcharge to preliminary amendments tends to increase burdens and risks on applicants.

The possibility of conversion errors arising at all and the burdens of requesting corrections have the potential to negatively impact applicants. Moreover, the increased applicant burden to format DOCX files, proofread converted files, and make separate preliminary amendment submissions is potentially significant unto itself. In effect, DOCX filing saves some effort and expense for the USPTO by pushing or shifting certain very large burdens and risks onto applicants. The supposed benefits to applicants are trivial or meaningless.

Best Practices for DOCX Filing

The following are some suggested practices for DOCX filing. These are meant to supplement or clarify USPTO-provided guidance and frequently-asked-question (FAQ) responses that often serve more as disingenuous “gaslighting” to deny problems filers have encountered and conceal unstated, de facto requirements than to provide reliable, practical, actionable guidance. While a document might be modified shortly before filing to meet minimum requirements or best practices, there can be risks and potential problems associated with doing so, including the introduction of inadvertent errors and potential file corruption. It also may be significantly more time-consuming to later modify an application document for filing than to prepare it in a compliant way from the start.

Top DOCX application compliance tips:

- Use paragraph numbering (required), preferably paragraph autonumbering using at least four digits inside square brackets (“[0001]”)

- Omit line numbering

- Manual paragraph numbering is compliant but makes changes and amendments very burdensome

- Often the lack of paragraph numbering in an existing application document is the single most burdensome formatting change required for DOCX filing compliance

- Use a supported font, such as times new roman or arial (note that supported fonts are subject to change without notice)

- There have been reports that some fonts the USPTO has explicitly identified as being supported are not actually fully supported

- While a document-wide font change action can be performed, it may not alter font in embedded equations or formulas, inserted images with text or alphanumeric characters, headers and footers, and the like

- Manually number claims with plain text numbers and avoid automatic “list” formatting using word processing program functionality

- USPTO systems will sometimes modify claims in numbered list format to number each clause within a claim separately, disrupting intended claim numbering

- Use of auto-updating cross-reference fields to indicate claim dependencies sometimes leads to errors in conversion, such as converting all claim dependency references to a prior claim from various numbers to zero (0)

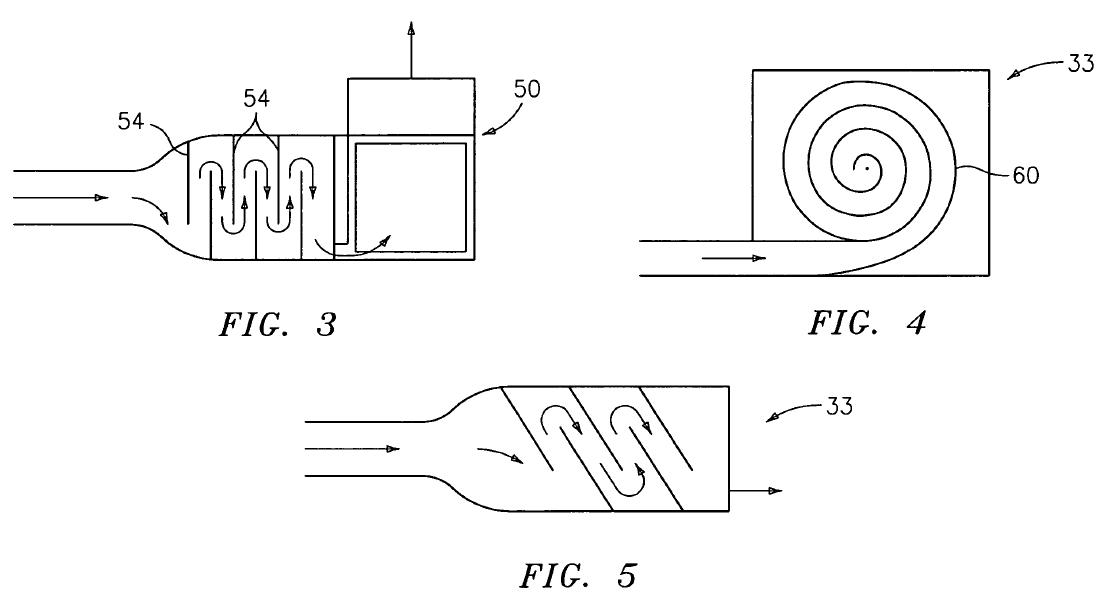

- Consider using an inserted image of a complex formula or equation rather than using one generated by a word processing program’s equation editor

- Inserted images must have sufficient resolution to be readable

- Images should be inserted in-line with text, without text wrapping (text wrapping for images and tables can produce errors with PDF conversions for an “Auxiliary PDF” submission)

- Provide figures in a separate document, rather than as pages of the same document containing the application text (specification)

- Deletion of pages containing drawings can sometimes produce unintended changes to the formatting of remaining pages in a DOCX file, such as deletion of page numbering, changes to margins, and the like

- Use an English version of the proprietary Microsoft Word® word processing program

- There are variants of the DOCX format and other nominally DOCX compatible word processing programs will not necessarily create files that will be processed the same way by the USPTO’s proprietary conversion engine

- Use of versions of the Microsoft Word® program intended for use with non-Latin character alphabets may render differently on an English-language version of that program, such as removing inter-word spacing. For example, “Balance SBCS and DBCS character(s)” options create warnings in Patent Center about possible reduction of pages

- Avoid use of highly customized application templates with macros or uncommon/complex embedded formatting settings

- Remove all “content controls”. The presence of “content controls” will make a DOCX file non-processable and unsubmittable. “Content controls” can be made visible by selecting File –> options –> customize ribbon and then selecting the box to make the “developer” tab visible, then, under the (now visible) developer tab, selecting “design mode”; the content controls should now be visible in the document between unique-looking (usually gray) leading and trailing tags.

- Simplify! In general, documents with simpler formatting are more likely to be compliant and less likely to result in conversion errors than more complexly formatted ones. Use complex, customized formatting only when strictly necessary or unavoidable

- The “.docx” file extension must be in all lowercase letters

The USPTO provides DOCX-compliant utility patent application templates that could optionally be used. There is a basic template and another with essentially all possible application section headings identified. The basic template will like be more appropriate in most situations, with fewer extraneous section headings that are likely inapplicable. However, the use of automatic list claim numbering in these templates can still cause conversion errors and is not seen as actually compliant; thus, manual text-only claim numbering should be used in place of the list-style autonumbering in those templates.

While the USPTO asserts that DOCX file metadata is automatically removed from documents when filed, it is recommended to independently assess and remove any sensitive metadata before filing. Such metadata could relate to document revisions and the like. While such information is not necessarily harmful to an applicant’s interests, its presence in filed documents might possibly increase litigation discovery burdens if a resultant patent is ever enforced. In Microsoft Word, accessing the “File” > “Info” menu and utilizing the “Inspect Document” feature can help identify and then remove metadata. But be careful not to remove necessary document fields like page numbers appearing in footer margins.

One difficulty with identifying errors is that meaningful proofreading requires first uploading the DOCX file to the USPTO’s Patent Center and then reviewing a USPTO-converted file. While Patent Center provides some feedback about certain possible DOCX compatibility issues during the file upload and submission process, such automated feedback will never identify substantive content errors such as unintended changes to numerical values or technically (that is, substantively) meaningful formatting.

An Auxiliary PDF can be filed without charge in addition to a DOCX file, and doing so is recommended. Although it is still a best practice to utilize a reliable DOCX file or pay the non-DOCX surcharge. That is because corrections premised on the contents of the Auxiliary PDF require, at a minimum, significant time and effort associated with formal petitions for correction. Also, in worst case scenarios, such petitions to correct DOCX-related errors might be denied, even if they result from USPTO-side problems. In this sense, Auxiliary PDFs might provide some benefit but are not an ideal or complete solution to the problems posed by DOCX filing.

Non-DOCX Filing Alternatives

In some instances, electronically filing an application in PDF format and paying the non-DOCX surcharge may be more efficient than spending considerable time proofreading converted documents to check for errors. “Last minute”, urgent, or rush filings of applications with potentially problematic equations, formulas, data tables, text formatting, or the like may not allow sufficient time for proofreading, and may suggest PDF format filing and payment of the non-DOCX surcharge.

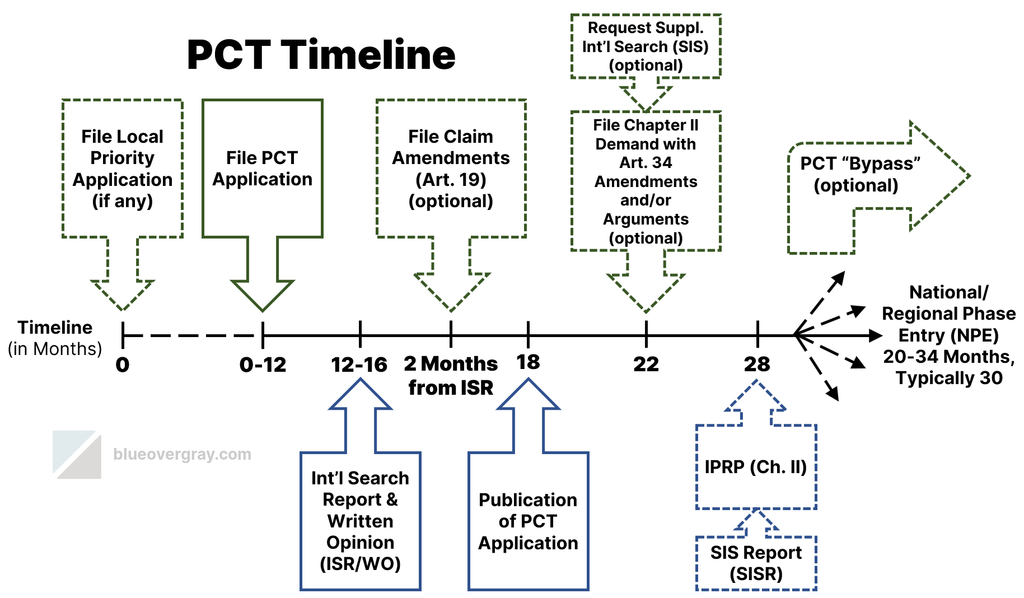

Filing a PCT application and entering the U.S. via the national phase (perhaps early) is another approach. Because PCT national phase entries are not currently subject to the non-DOCX surcharge, many difficulties are avoided. However, there are different rules and official fees associated with PCT applications that may (or may not) be significant. For instance, for national phase entries, “Track One” prioritized examination is not available and filing a request for continued examination (RCE) requires first submitting all inventor declarations/oaths. And this approach is usually more expensive than paying the non-DOCX surcharge, although some fee deferrals and other additional benefits can arise through PCT filings.

Additionally, if the USPTO’s Patent Center system is unavailable and paper (hard copy) filing via express mail is required to meet a filing deadline or bar date, payment of official non-DOCX and paper-filing surcharges might be necessary.

Austen Zuege is an attorney at law and registered U.S. patent attorney in Minneapolis whose practice encompasses patents, trademarks, copyrights, domain name cybersquatting, IP agreements and licensing, freedom-to-operate studies, client counseling, and IP litigation. If you have patent, trademark, or other IP issues, he can help.