Official fees for U.S. patent applications depend on the size of the applicant(s), plus that of any licensees, affiliates, or other associated parties. There are different fee rates applied to large, small, and micro entities. What follows is an explanation of how to determine if large, small, or micro entity fees apply.

Large Entity (Undiscounted) Status

By default, all applicants are subject to large entity official fees. Large entity fees are also called undiscounted fees. A for-profit business having more than 500 employees (including employees of affiliates) is a large entity. But, really, the best way to look at undiscounted or large entity status is to say that it applies whenever any applicant does not qualify for reduced fees as a small or micro entity.

If there are multiple applicants, undiscounted (large entity) fees must be paid if any of them fail to qualify for reduced fees as a small or micro entity.

Also, an applicant is required to pay undiscounted (large entity) fees if sufficiently connected with a large entity, such as through an affiliation, assignment, obligation to assign, licensing agreement, joint ownership, or shop rights.

Small Entity Status

Qualifying as a small entity allows for discounted official fees. Small entity fees are generally forty percent (40%) or two-fifths of large entity fees. Though not all fees or surcharges are eligible for a small entity discount.

To qualify for small entity status, the applicant(s) must each be a person, small business concern (having no more than 500 employees, including those of affiliates), or nonprofit organization (including non-profit universities and certain non-profit scientific or educational organizations). But an applicant is required to pay undiscounted (large entity) fees if associated with an entity that does not qualify as a small entity, such as through an affiliation (a potentially confusing circumstance explained further below), assignment, obligation to assign, licensing agreement (subject to certain exceptions discussed below), joint ownership, or shop rights.

In general, entities are affiliates when one has the power to control the other or a third party has power to control both. However, affiliation under that standard is assessed based on the totality of the circumstances. For instance, an affiliation with a single shareholder (or a group of shareholders) holding less than 50% of the voting stock can be present if that minority block of stock is large compared to other outstanding blocks of voting stock and provides “negative control” through veto power over an important aspect of the business concern. Accordingly, an affiliation with a venture capital firm or the like having sufficient control over a portfolio of multiple companies can mean that employees of all affiliate companies in that portfolio are aggregated together when assessing the 500-employee limit. As another example, an affiliation can be established when one firm relies on a second firm (including a customer) for 70% or more of its revenue in a longstanding relationship, due to economic dependence, meaning the employees of the second firm are counted against the total of the first firm. Contractual relationships short of ownership are also considered.

There are certain exceptions to the types of licenses that result in loss of small entity status. Firstly, a license or similar transfer of rights in the invention is only relevant if it involves a U.S. application or patent. A license involving only a related foreign application or patent would not affect U.S. small entity size status, for instance. Moreover, implied licenses to use and resell patented articles purchased from a small entity will not preclude the proper claiming of small entity status. Also, a use license to the U.S. Federal Government does not result in loss of small entity status.

A security interest (such as using a patent or application as collateral for a loan) does not result in loss of small entity status unless there is a default that triggers the security interest. An inventor or applicant retaining a firm to build a prototype of an invention for the applicant’s own use is not considered to constitute a license for purposes of the small entity definition.

Small entity status requires claiming that status, such as on an Application Data Sheet (ADS). However, there is no further certification or supporting evidence required.

If small entity status is lost, the applicant must submit a notification of a loss of entitlement to small entity status. However, once small entity status has been established, fees can continue to be paid at the small entity rate without regard to the change in status until the issue fee is due or any maintenance fee is due. In other words, an established small entity fee status remains in effect during ongoing examination of an application and discounted small entity fee rates are only formally lost at the time of issue fee payment (after allowance) or when the next patent maintenance fee is due.

Any attempt to intentionally establish inaccurate status as a small entity, or pay fees as a small entity, is considered fraud on the USPTO. Such fraud can make a resultant patent unenforceable. Also, the USPTO can assess a fine—even after a patent has issued—of no less than three (3) times the amount that was unpaid due to a false certification of small entity status.

It may be possible to correct errors related to payments at the small entity rate. If small entity status is established and small entity fees are paid in good faith, and it is later discovered that small entity status was established in error or through error the USPTO was not notified of a loss of small entity status, the error will be excused upon compliance with separate submission and itemization requirements plus a fee deficiency payment. The deficiency amount owed is calculated using rates in effect on the date upon which the deficiency is paid, not the fee rates at the time of the original (but deficient) payment. There is no time limit for such corrections.

A refund is possible, for fees timely paid in full (that is, at the undiscounted large entity rate) prior to establishing small entity status. However, such refund requests must be made within three months of the date of the timely payment of the full fee. Yet the costs and burdens associated with requesting such refunds may exceed the value of the refund in many cases.

Micro Entity Status

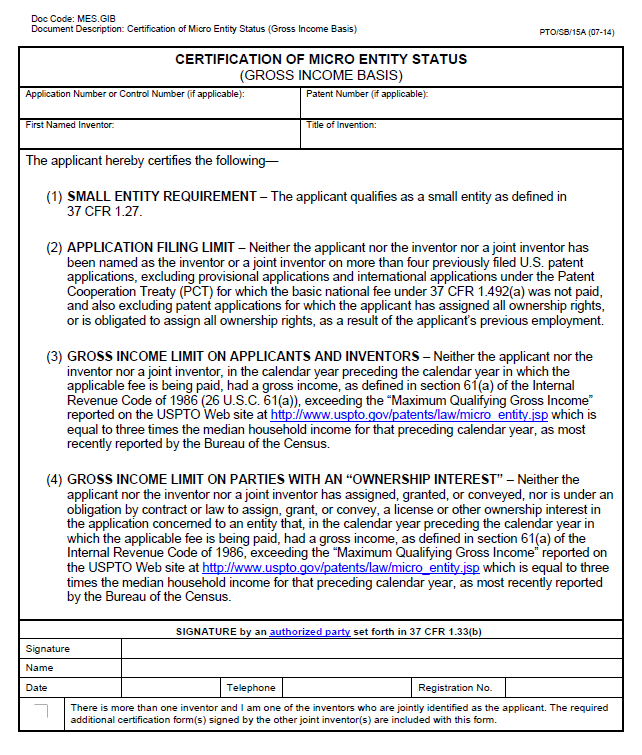

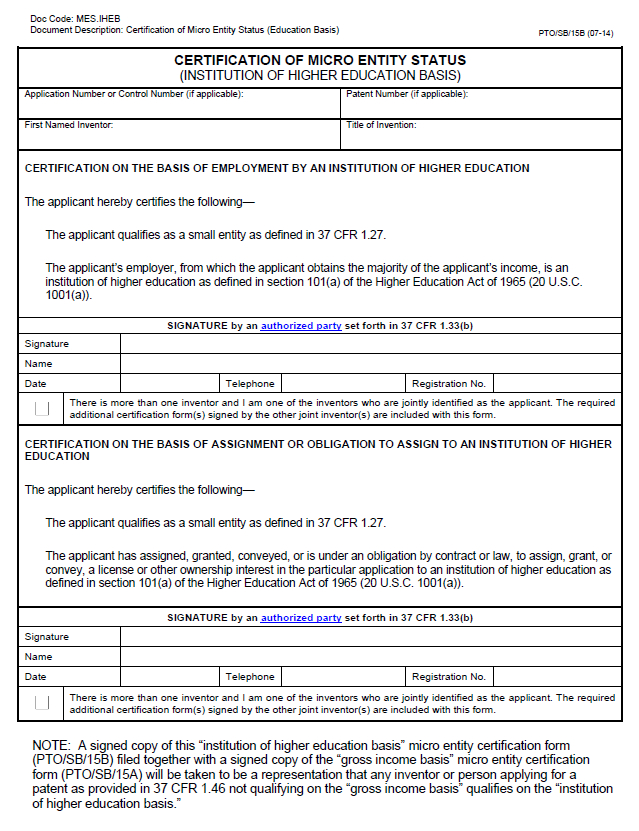

There are two possible bases for micro entity status: gross income basis and institution of higher education basis. The requirements for each are rather confusing. Micro entity compliance requirements are also more burdensome than for small entity status. Micro entity fees are generally half (50%) of small entity fees and a fifth (20%) of large entity fees. Though not every official fee/surcharge is eligible for a micro entity discount.

To qualify for micro entity status—gross income basis, the applicant(s) must each certify the following:

(i) the applicant qualifies as a small entity

(ii) no applicant or inventor has been named as an inventor on more than four previously filed U.S. non-provisional patent applications (including PCT applications designating the U.S.)

(iii) no applicant or inventor had a gross income in the previous year of more than the “Maximum Qualifying Gross Income,” which is three times the median household income (as of September 10, 2024 that was $241,830 (USD) but that amount changes yearly), and

(iv) no applicant or inventor has assigned, granted, or conveyed, or is under an obligation to assign, grant, or convey, a license or other ownership interest to another entity that does not meet the “Maximum Qualifying Gross Income” limit.

For the previously filed application limit, applications resulting from prior employment are not counted against the total. So an applicant/inventor is not considered to be named on a previously-filed application for micro entity status purposes if he or she has assigned, or is under an obligation by contract or law to assign, all ownership rights in the application as the result of his or her previous employment—this exception does not apply to prior applications as part of current employment, however. Also excluded from the total are any PCT applications for which the basic national phase entry fee to enter the U.S. was not paid. Lastly, USPTO guidelines say that the filing of a future application will not jeopardize entitlement to micro entity status in any of the (up to five) applications already filed.

Income in a foreign currency must be converted to U.S. dollars using Internal Revenue Service (IRS) exchange rates.

To qualify for micro entity status—institution of higher education basis, the applicant(s) must each qualify as a small entity and certify micro-entity status. But there are two possibilities. Each micro entity applicant (that qualifies as a small entity) must either:

(A) obtain the majority of their income from a United States institution of higher education; or

(B) have assigned, granted, or conveyed, or be under an obligation by contract or law to assign, grant, or convey an ownership interest in the application to such a United States institution of higher education.

Importantly, the institution of higher education basis for micro entity status also requires that the inventor(s) be the applicant(s), not the university.

Both possibilities for micro entity status require that all applicant(s) qualify as a small entity. Small entity status might be lost if there is a license granted to a large entity, for example. However, the micro entity requirements do not exclude licenses for U.S. Federal Government use, meaning that an exception allowing certain applicants to qualify for small entity status does not apply for micro entity status. Also, the micro entity regulations do not explicitly refer to security interests, making it unclear if they are treated the same as for small entity status.

All applicants must still be entitled to micro entity status to pay a fee in the micro entity amount at the time of any official payments. Written certification is required to initially establish micro entity status. But more is required after establishing that status. It is further necessary to determine whether the requirements for micro entity status exist at the time each fee payment is made. Also, if the prosecution of an application under the gross income basis status extends across multiple calendar years, each applicant, inventor, and joint inventor must verify that the gross income limit for the requisite calendar year is met to maintain eligibility for the micro entity—gross income basis discount. And under the institution of higher education basis, each applicant, inventor, and joint inventor potentially must verify that a majority of his or her income comes from a U.S. institution of higher education. These requirements make micro entity status compliance more onerous than for small entity status. Unlike with small entity status, micro entity status can be lost during ongoing examination of an application.

Whenever micro entity status is lost, it is necessary to file a formal notification of loss of entitlement to micro entity status. As explained above, loss of micro entity status can potentially occur at any time. So a notification of loss of micro entity status can generally not be deferred and must be filed promptly (and before any official payments) when an applicant or inventor’s status changes. Small entity status may or may not still be available if micro entity status is lost.

Any attempt to intentionally establish incorrect status as a micro entity, or pay fees as a micro entity, is considered fraud. Such fraud can make a resultant patent unenforceable. Also, the USPTO can assess a fine—even after a patent has issued—of no less than three (3) times the amount that was unpaid due to a false certification of micro entity status.

It may be possible to correct errors related to payments at the micro entity rate. If micro entity status is established and micro entity fees are paid in good faith, and it is later discovered that micro entity status was established in error or through error the USPTO was not notified of a loss of micro entity status, the error will be excused upon compliance with separate submission and itemization requirements plus the fee deficiency payment. The deficiency amount owed is calculated using the date on which the deficiency is belatedly paid, not the fee rates at the time of the original (but deficient) payment.

There is no possibility for refunds of previously-paid fees based on later establishment of micro entity status. In this respect, micro entity status does not provide a window for requesting a refund of previously-paid fees as is possible for subsequent establishment of small entity status. Although if the fees were originally paid at a large entity rate a refund of the difference between undiscounted and small entity rates may be possible when micro entity status is establish, because micro entity status requires that the applicant also qualify as a small entity.

Austen Zuege is an attorney at law and registered U.S. patent attorney in Minneapolis whose practice encompasses patents, trademarks, copyrights, domain name cybersquatting, IP agreements and licensing, freedom-to-operate studies, client counseling, and IP litigation. If you have patent, trademark, or other IP issues, he can help.