Important Developments

As 2025 begins, some recent and upcoming changes in patent and trademark practice before the U.S. Patent & Trademark Office (USPTO) for patent and trademark matters merit attention, along with developments from U.S. courts pertaining to those areas of intellectual property (IP) law. (Click the preceding links to jump to desired content).

Patents

Massive official patent fee increases for 2025

The USPTO will impose significant official patent fee increases starting January 19, 2025. Materials related to the patent fee increases can be found here, including an Executive Summary of the most notable official patent fee increases and wholly new official fees plus a spreadsheet showing all old and new fees and the difference between them. The Executive Summary and spreadsheet should be consulted because of the sweeping extent of the official fee schedule changes and because many initial proposals were modified or eliminated in the final rule.

[EDIT: The USPTO spreadsheet detailing the new official fee schedule confusingly listed extension of time fees as both having no increases and as having 7-8% increases for non-provisional applications. The text of the final rule suggested that these fees would increase, without specifying what those increases would be. It is believed that patent extension of time fees are increasing for non-provisional applications.]

The general nature of this round of fee setting activity is that the USPTO is charging much more and, in some areas, also doing less. As just a few selected examples, the USPTO is imposing new tiered fees for continuing applications (with large fees required if a new continuing application is filed more than six or nine years after the earliest priority date), new fees if the number of cumulative citations submitted with information disclosure statements (IDSs) exceed tiered thresholds of 50/100/200 references, higher excess claim fees, a huge increase in the fee for patent term extension (PTE) requests (which are not to be confused with patent term adjustment (PTA) determinations), and large increases in design patent application fees. Legislation a few years ago increased official fee discounts to small and micro entities, and the new official fees are in large part an effort by the USPTO to avoid any overall reductions in total fees collected.

AFCP 2.0 discontinued

The widely-used After-Final Consideration Pilot (AFCP) 2.0 program was discontinued as of December 15, 2024. The USPTO had previously proposed imposing a significant official fee for what previously carried no official fee. Feedback on the proposed fee requirement indicated that applicants did not believe the program provides enough benefit to justify the proposed cost. In response, the USPTO decided to eliminate the AFCP program entirely.

Applicants should understand that examiners spend very little time reviewing after-final responses and amendments, perhaps as little as 30 minutes, with a request for continued examination (RCE) and payment of the associated fee being needed in order for submissions to receive further consideration by the examiner. Applicants seeking to avoid RCE fees should also carefully consider how they respond to a first non-final office action on the merits, knowing that subsequent amendments and arguments after a final office action may receive only cursory consideration and may not be entered. Making claim amendments earlier can reduce the potential need for an RCE, if cost containment is more important than aggressive maximization of claim scope.

Assignment recordation developments

Legacy USPTO platforms for patent and trademark assignment recordation were replaced with a new unified platform called Assignment Center on February 5, 2024. There was no beta testing of this new platform prior to its launch.

While the new Assignment Center platform offers a graphical user interface with a modernized appearance, it eliminated certain features and provides reduced user functionality compared to the old systems. Submissions now require that the user login first. Most significantly, the ability to save draft submissions shared between different users was eliminated, making it more difficult for attorneys and support staff to meaningfully work together on assignment recordations. USPTO representatives have informally commented that there are plans to (re)introduce such collaboration functionality, but there have been no formal announcements about when (if ever) that functionality will be reintroduced. Also, the new platform no longer permits a patent assignment recordation submission to simultaneously serve as an inventor oath/declaration submission too (a separate oath/declaration submission in Patent Center is required).

Although the USPTO had recently proposed re-instituting a fee for electronic assignment recordations, that proposal was not implemented. Electronic assignment recordations will continue to carry no official fee, for the time being. Hard copy assignment recordations, submitted by mail, will continue to require an official fee.

Also, it was revealed in August of 2024 that the configuration of the USPTO’s Patent Center system led to the (potential) release of limited amounts of confidential information about unpublished patent applications between 2017 and 2024. This information was linked to recorded assignment data submitted through other assignment platforms, via an “Assignments” menu option in Patent Center listings for individual matters (which is now disabled unless applicants request that it be enabled). The information that was publicly accessible included the title of the application, application serial number, application owner name, application filing date, and name(s) of the inventor(s). Unauthorized viewing of confidential application information is not believed to be widespread, and substantive contents of unpublished applications was not made available. The limited nature of the information made public does not appear to pose significant concerns for most applicants. But this represents yet another problem added to a long list of debacles with USPTO online systems.

More types of e-signatures now accepted

Beginning March 22, 2024, the USPTO began accepting more types of electronic signatures on documents subject to USPTO signature rules. It is now possible to use a suitable document-signing software tool (DocuSign®, etc.) if two requirements are met: (i) the software tool must be specifically designed to generate an electronic signature and preserve signature data for later inspection in the form of a digital certificate, token, or audit trail; and (ii) the software tool must result in the signature page or electronic submission form bearing an indication that the page or form was generated or electronically signed using document-signing software. If those requirements are met, it is not necessary for this type of electronic signature to include slashes (as were previously required). Common commercial e-signature tools using will be able to satisfy these requirements, and typically will do so automatically under normal usage and settings. All of the previous types of electronic signatures accepted by the USPTO can continue to be used.

However, it is important to note that USPTO e-signature rules apply only to powers of attorney (POAs), inventor oaths/declarations, and other correspondence. USPTO signature rules do not control for assignments, for which applicable (local state/foreign) contract law will generally apply instead.

More information about electronic signatures in relation to U.S. patent matters can be found here.

AI-assisted inventorship

Guidance about inventorship when AI tools are utilized was issued by the USPTO in early 2024. In brief, the USPTO has so far taken the position that only humans can be inventors for patenting purposes. The issued guidance focuses on how to evaluate the use of AI to assist a human inventor, and the sufficiency of human contributions. A human must make a “significant contribution” to be an inventor, according to the USPTO. It is important to proactively consider the potential that AI was used in conceiving new inventions, so that inventorship can be determined and named properly. This remains an evolving area and the USPTO may possibly alter or elaborate its positions about AI-related issues at some time in the future.

Guidance regarding means-plus-function claiming

In March of 2024, a memorandum was issued to USPTO examiners providing guidance about interpreting means-plus-function limitations in patent application claims. That memo was intended to encourage examiners to identify means-plus-function limitations, to make relevant interpretations explicit in the prosecution history, and to ensure that such limitations have adequate support. U.S. patent law generally requires peripheral claiming, and prohibits central claims except under the limited exception of means-plus-function (or step-plus-function) limitations in a claim for a combination.

Means-plus-function recitations are often considered narrow, in contrast to treatment of “means” language in various other countries. Applicants and their counsel often seek to essentially obtain central claims without being limited to narrow means-plus-function interpretations, by using nonce words and functional terminology—like “[function] unit,” “[function] module,” “[function] system,” “[function] mechanism,” “[function] element,” “[function] member,” and the like. The main issue is whether a person of ordinary skill in the art would understand the term to refer to structure or instead merely be a generic placeholder for all possible ways of achieving the stated function (or functional result), with the latter approach raising concerns about impermissible central or preemptive claiming. The Federal Circuit has held that claim recitations that do not use the phrase “means for” may be interpreted as means-plus-function limitations in some circumstances. This approach tends to save applicants and patentees from themselves, because the alternative, as suggested by Supreme Court precedent and explained in detail in USPTO administrative decisions, is that purely functional claim limitations at the point of novelty that fail to use the phrase “means for” are invalid. Although a means-plus-function interpretation may still lead to indefiniteness concerns, if the accompanying description and figures fail to adequately disclose corresponding structure—such as by merely repeating the same functional language or conclusory statement of results without further explanation of the particular structure(s) used to achieve the stated function or result.

U.S. examiners have begun making means-plus-function interpretations more explicit more often in recent years, but they still fail to do so in all instances. More information about functional language in claims, disclosure requirements for means-plus-function claiming, and best practices are available here, here, and here.

New revision of MPEP released

The Manual of Patent Examining Procedure (MPEP) was updated in November 2024 to the 9th Edition, Rev. 01.2024. This revision is meant to be up-to-date with respect to USPTO policies and procedures as of January 31, 2024. A summary of changes can be found here, although this summary is very general and somewhat vague about specific changes.

Patent term adjustment calculation errors

In yet another instance of the USPTO incorrectly calculating patent term adjustment (PTA), it was announced that patents issued from March 19, 2024 through July 30, 2024 were subject to a software “coding error” that resulted in incorrect PTA numbers appearing on approximately 1% of granted patents from that time period. However, it is left to individual patentees to investigate PTA calculations and make a timely request for recalculation. People often express surprise that the term of a U.S. patent cannot be stated simply. Instead, determining patent term requires that members of the public (and the patentee) investigate numerous factors, including possible PTA, patent term extension (PTE), and terminal disclaimer term reductions, and then perform a calculation. Patentees must undertake their own analysis of USPTO PTA calculations, and if errors are discovered must request correction within certain time periods (two months extendable up to seven months from grant). Official fees are being waived for timely requests to correct USPTO errors due to this particular software error. But other petitions for PTA correction carry an official fee that is not refunded even if the PTA was incorrect due to some other USPTO calculation error.

Terminal disclaimer rulemaking abandoned

The USPTO has withdrawn proposed changes to terminal disclaimer requirements. The proposal would have more sharply limited patentee rights when a terminal disclaimer is filed to overcome a double patenting rejection. The proposal was met with significant opposition, including criticism that the USPTO lacked authority to impose the proposed rules. While the USPTO meant well by trying to address overreach and greediness by patentees who burden the public with large patent family “thickets” that are (by design) expensive to avoid or challenge, the proposal did seem to exceed USPTO authority and contradict statutory provisions. For now, the USPTO has left existing terminal disclaimer requirements and procedures as-is.

DOCX filing developments

The deeply unpopular official surcharge for U.S. non-provisional utility patent applications submitted in a non-DOCX file format has been in effect since January 2024. Since that requirement went into effect, the USPTO has belatedly clarified some policies and had modified how its electronic filing system Patent Center handles DOCX files, sometimes with formal announcements and sometimes without any clear notice. Practitioners and applicants have had to struggle to understand unclear and shifting treatment by the USPTO, making it difficult to provide clear guidance for how to avoid the official surcharge. There have been numerous instances of surprise official charges by the USPTO.

One belated clarification was that applications filed in a language other than English (with a simultaneous or later-filed English translation) must be in DOCX format to avoid the surcharge. Patent Center’s handling of DOCX files in other languages, using fonts and characters that may not be supported, presents challenges and risks to applicants. This requirement, which was first announced by the USPTO only in a Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) response after the non-DOCX surcharge went into effect but not in any official rulemaking notice, provides no substantive benefits to the USPTO or to applicants, except that it provides another opportunity for the USPTO to impose official surcharges.

Also, the USPTO began imposing the non-DOCX surcharge (without warning or notice, and contrary to certain prior indications) when preliminary amendments are filed together with a new application in a non-DOCX format. This surprised many practitioners, because the USPTO had previously been recommending against submitting amendments in DOCX format. And it was not until November 13, 2024 that Patent Center was modified to permit a DOCX format preliminary amendment to be filed together with a DOCX application in a single submission (before then practitioners had to make separate submissions on the same day, which was cumbersome). The USPTO has still not clarified how substitute specifications should be submitted with preliminary amendments to avoid non-DOCX surcharges, meaning such submissions remain highly cumbersome and their treatment unclear unless the surcharge is paid.

Additionally, without any clear announcement, the functionality of Patent Center was changed sometime in 2024 so that tracked changes redlines in DOCX format amendments are now converted to strikethrough and underlining formatting during submission, instead of being “entered” and the mark-ups no longer being explicitly visible as Patent Center initially handled such formatting. This underscores how the operation of the USPTO’s Patent Center platform for the processing and rendering of DOCX-format files may suddenly be different than expected on any given day, without advance warning.

USPTO procedures for handling of DOCX format files continues to change over time. Guidance for creating application documents (hopefully) compliant for USPTO DOCX filing is available here. But applicants with complex application content should consider the possibility of paying the non-DOCX official surcharge and filing applications in PDF format to avoid the risks associated with USPTO-generated errors in substantive application content.

Revision to USPTO authority to impose fines

In 2022, a law was passed giving the USPTO authority to impose fines of up to three times the amount of official fees an entity failed to pay for “falsely” asserting small entity status or “falsely” certifying micro entity status. (codified in 35 U.S.C. §§ 41(j) and 123(f)). There is no time limit in the statute for imposition of such fines, nor any upper limit on the amount of those fines. Since then, the USPTO has not created any rules to implement its fining authority. For instance, the USPTO has not established any schedule of rates for such fines, nor any formal procedures for how determinations of false assertions/certifications are to be made. A worrying aspect of the original law was that it provided no exceptions for honest mistakes. So it appeared that even a clerical error or honest misunderstanding could lead to potentially large (even unlimited) fines. A December 2024 revision to those laws now adds exceptions to allow an entity to show that an assertion or certification was made in good faith to avoid a USPTO fine. This exception therefore limits USPTO fining authority to situations where a fine is justified as a penalty for bad faith action. However, the law as revised still places no upper limit on the amount of these fines.

Riyadh design law treaty signed

The diplomatic conference in Riyadh, Saudia Arabia in November 2024 concluded with the adoption of a design law treaty. The impact of this treaty on the United States remains to be seen. It will be some time before the treaty as negotiated is actually implemented anywhere. It is unclear if any significant changes to U.S. design practice will result form this treaty. Although the treaty may bring some other jurisdictions into further harmonization. But the treaty appears to stop well short of complete international harmonization of the treatment of designs. For instance, the U.S. will continue addressing designs as a type of patent right but other countries will continue treating design registrations as something other than a patent right.

Vidal steps down as director of USPTO

Kathi Vidal stepped down as Under Secretary of Commerce for Intellectual Property and Director of the USPTO as of December 13, 2024. Derrick Brent, the Deputy Under Secretary of Commerce for Intellectual Property and Deputy Director of the USPTO has become acting Director until a new Trump administration appointee is confirmed.

New collective bargaining agreement

The USPTO and the Patent Office Professional Association (POPA) signed a new collective bargaining agreement (CBA) on December 11, 2024, an agreement that was last formally updated in 1986. The USPTO announced that the agreement had been signed, without making it available on the USPTO web site. POPA, however, has made the agreement available on its web site. There are many interesting documents available from POPA that provide insight into the patent examination process. For instance, POPA provides information about the “count” system that governs examiner work quotas.

More U.S. patent filing information

Please also see the Guide to Foreign Priority Patent Filings in the USA for in-depth discussion of requirements for foreign applicants to file U.S. counterpart patent applications with a foreign priority claim. Additional basic information about patenting can be found in the Patent Basics guide.

Trademarks

New trademark fee structure and fee increases for 2025

The USPTO will impose official trademark fee increases and a new structure for trademark fees starting January 18, 2025. Materials related to the new trademark fees can be found here, including an Executive Summary of the most notable official trademark fee increases and new structure for trademark fees plus a spreadsheet showing all old and new fees and the difference between them.

As part of the new trademark fee rule, the naming convention and types of fees are changing. For example, a typical trademark application would see at least a $100 fee increase. And, if custom identifications of goods/services are used rather than merely selecting ones from pre-approved descriptions from the Trademark ID Manual, then new “premium” surcharges of $200 per class would apply. This means that typical new trademark applications will see official filing fees increase by $300, and possibly more. Due to an inability to change the fee structure to impose new surcharges in Madrid Protocol extensions to the USA, the existing Madrid Protocol (§ 66) fee structure will remain but with those fees increasing by 20%.

Various other fees are being created or increased. For instance, a new $100 fee (per class) for “insufficient information” has been created, covering any deficiencies (or mistakes) in satisfying the first nineteen requirements of 37 C.F.R. § 2.22(a) (that is, all listed requirements except for a foreign applicant’s failure to designate a U.S. attorney). Those fees will include things like failure to include a translation or transliteration, failing to provide complete information about the applicant, failing to provide a description of a mark with graphical design elements or stylization, failure to include a statement about use of color, or a failure to claim ownership of prior registrations. Also, there is a new surcharge of $200 (per class) for each additional group of 1,000 characters beyond the first 1,000 characters. Some fees specific to intent-to-use (ITU) applications will increase by 25% or 50%, and post-registration maintenance/renewal fees will increase from 5-44%. Petition fees will generally increase by 60% or more, and there will be a 400% increase in the official fee for a letter of protest. However, extension of time fees in trademark matters have remained unchanged, without any increases.

Targeted trademark audits

USPTO audits of trademark registrations had been conducted on a random basis since 2017 during the post-registration maintenance process. However, given the rise of so-called “specimen farm” websites used to generate fake or fraudulent specimens of use in addition to the prevalence of digitally altered /or fraudulent specimens, the USPTO expanded its audit program to further include targeted or ”directed” audits starting October 28, 2024. The expanded audits are meant to address “systemic efforts to subvert the requirements for use in commerce of a mark to support registration.”

Once initiated, these directed audits will happen in the same manner as with random audits. The USPTO has said only that directed audits can take place when submitted documents “exhibit certain attributes that call into question whether a mark is in use in commerce in the ordinary course of trade.” But apart from vague references to altered specimens and specimen farms, the USPTO has not disclosed what “certain attributes” will trigger a directed audit, making this process essentially discretionary. On the one hand, the USPTO desires to keep its discretionary directed audit procedures secret, so that entities responsible for fraudulent submissions cannot seek to avoid detection and exposure. But, on the other hand, unlimited discretion raises due process and fairness concerns, including the possibility of scapegoating.

New trademark filing systems

In addition to having recently replaced the legacy trademark search platform and the trademark assignment filing platform, the USPTO will retire its Trademark Electronic Application System (TEAS) platform used for new application and prosecution filings on January 18, 2025. A new Trademark Center platform, currently in Beta release, will take the place of TEAS.

Additionally, the Trademark Trial and Appeal Board (TTAB) will retire its legacy Electronic System for Trademark Trials and Appeals (ESTTA) filing system sometime in the spring of 2025. A new TTAB Center platform, currently in beta release, will replace ESTTA.

New revision of TMEP released

The Trademark Manual of Examining Procedure (TMEP) was updated in November 2024. This update incorporates relevant precedential decisions issued since the prior May revision and before August 31, 2024. It also revises language to make the TMEP gender neutral and replaces references to the Trademark Electronic Application System (TEAS) and the Electronic System for Trademark Trials and Appeals (ESTTA) with generic wording, because they will be retired shortly and replaced with Trademark Center and TTAB Center, respectively. A complete change log can be found here.

More U.S. trademark filing information

Please also see the Guide to Trademark Registration in the USA for in-depth discussion of requirements for foreign applicants to file U.S. federal trademark applications. Additional basic information about trademarks can be found in the Trademark Basics guide.

Significant Developments in U.S. Courts

Obviousness for design patents

U.S. design patent practice has seen a number of significant shifts and important court decisions in recent years. In the case LKQ Corp v. GM Global Tech. Operations LLC, the obviousness standard applied to design patents was clarified as being the same as that applied to utility patents. A different standard (called the Rosen-Durling framework) that had previously made it incredibly difficult to ever find a design obvious was finally overruled. But it has been emphasized that analogous arts requirements still apply to references cited for obviousness. However, what the analogous art requirements will or might mean specifically in the design context remains to be seen.

Following the LKQ decision, the USPTO issued some limited guidance to examiners. But that guidance leaves many open questions and it stopped well short of making the sorts of significant changes to design application examination for obviousness that LKQ suggests. It may take a many years before enough design patent obviousness questions reach courts before the true impact of the LKQ case will be clear.

Third-party litigation funding

The funding of court litigation by a third party has received much attention, particularly in relation to the relationship between such funding arrangements and so-called “patent troll” litigation. While litigation funding can help promote access to justice, on the other hand it can skew litigation towards frivolous claims that revolve more around actual or threatened litigation costs than the true merits of the case, and funders may end up capturing so much of the benefit that the inventor or patentee is exploited in ways the eviscerate any purported access to justice benefits. Third-party function of civil lawsuits involving IP assertion have a particularly high risk of using the high cost of a legal defense as a cudgel to seek a nuisance-value settlement.

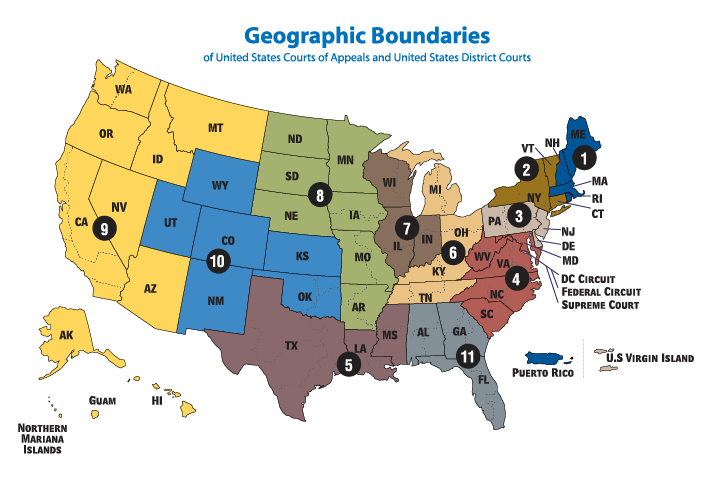

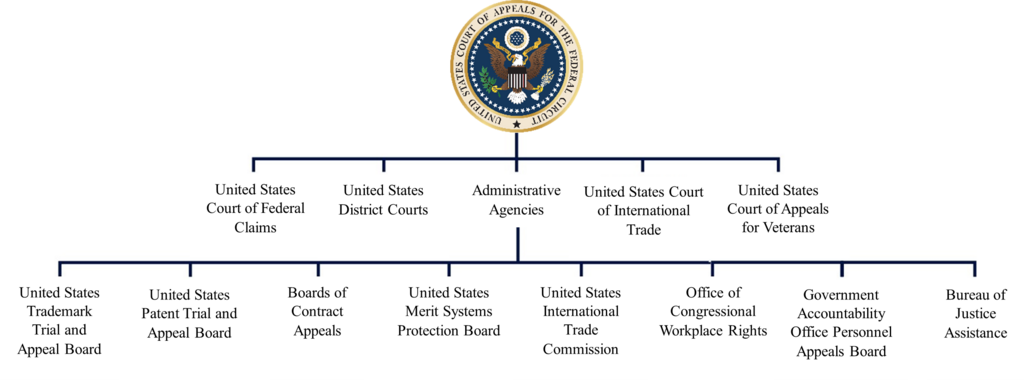

In terms of new developments and investigations into this issue, there was a recent Government Accountability Office (GAO) report, and the Department of Justice (DOJ), U.S. Judicial Conference’s Advisory Committee on Civil Rules, and congress / the legislature are all investigating or contemplating action on the issue. However, some recent interest in this topic is sadly colored by politicized xenophobic and imperialist machinations rather than being purely about justice and fairness. Current activities have primarily focused around third-party funding disclosure requirements in civil litigation, like Chief Judge Connolly’s standing order for disclosure of funding arrangements for cases before him in the District of Delaware.

Crisis of legitimacy in judiciary continues

The legitimacy of U.S. courts remains low in the eyes of the general public, to the point that public confidence in the courts has been described as “withering”. The U.S. Supreme Court has engaged in blatantly partisan realpolitik activism of late. This comes on top of recent investigative reports by journalists and a U.S. Senate Committee on the Judiciary report on ethics challenges at the Supreme Court, which document ongoing and rampant ethics problems and what looks like bribery and influence peddling. And, specifically in the IP field, Judge Pauline Newman remains suspended from the Federal Circuit, the court with exclusive appellate jurisdiction over patent lawsuits, due to her ongoing refusal to cooperate with an investigation into her fitness due to health issues and her treatment of court staff. Judge Newman’s conduct has reflected poorly on her, although it also has a partisan character in relation to the presidential judicial appointment system that will determine who will replace her if she finally steps down from the bench.

Additionally, the Judicial Conference of the United States issued non-binding guidance in March 2024 promoting the random assignment of cases to deter “judge-shopping”. The Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts was considering a binding rule for random case assignment, but that possibility was later apparently abandoned. The issue of judge-shopping typically involves judicial districts with single-judge divisions, which create the possibility that cases dealing with issues of importance to the entire nation can be filed there knowing that they will be assigned to a judge with a favorable ideology and political persuasion. This is much like forum-shopping but is judge-specific and therefore even more potent. This tends to allow parties to leverage the attitudes of a few individual federal judges, which may be extremist minority views that are deeply unpopular, to try to reshape the laws and their interpretation across large regions or even the entire country. This is most often the case when politically reactionary positions hostile to civil rights or public benefits are laundered through courts in the U.S. south. But in the IP field this also has happened in Texas where certain judges have taken positions favorable to “patent trolls.” There is a profoundly undemocratic character to how this process unfolds. The very fact that random case assignment is being opposed is an embarrassment and a sign of the dysfunctional nature of the U.S. government these days, which shows signs of becoming worse rather than better in the near future.

PTAB procedural rules

Lastly, multiple new rules were implemented for Patent Trial & Appeal Board (PTAB) administrative court proceedings at the USPTO. The use of rulemaking, rather than less formal guidance and procedural mechanisms, was generally intended to provide more stability to PTAB proceedings despite changes in USPTO leadership. However, the practice of discretionary denials of PTAB trials and director review are still nothing more than tinkering at the edges of a system that remains plagued by political whims, an issue that has been with the USPTO since it was founded.

December 2024

Austen Zuege is an attorney at law and registered U.S. patent attorney in Minneapolis whose practice encompasses patents, trademarks, copyrights, domain name cybersquatting, IP agreements and licensing, freedom-to-operate studies, client counseling, and IP litigation. If you have patent, trademark, or other IP issues, he can help.