Introduction — Why This Matters

Businesses often hire vendors to develop things for them, perhaps due to a lack of expertise in some particular area or just a lack of capacity. The vendor might be another firm, an individual independent freelancer, a temporary contractor working on-site, or some other type of consultant. This is often referred to as outsourcing. But who owns the intellectual property (IP) for things the vendor creates? This question should be asked at the beginning of a vendor relationship. Ideally, it should be answered before hiring the vendor.

All too often businesses ignore ownership of IP rights until there is infringement or a big business deal long after the vendor was hired. But cutting corners or forgetting to put IP ownership in writing at the beginning of a vendor relationship can potentially have huge (if avoidable) consequences later on. Businesses do come to regret such oversights later on. For instance, when selling a business, a prospective buyer might raise questions about lack of IP ownership due to vendor or outside contractor involvement, which might present barriers to completing the sale or might lower the purchase price. Or, when there is infringement, a business lacking ownership will not have standing to sue the infringer while the vendor (who still owns the IP) may be unconcerned and disinterested.

A common mistake is to wrongly assume that merely paying a vendor automatically transfers IP ownership or that receiving physical copies (even the sole original) transfers IP ownership. In the absence of something in writing, the vendor most likely retains any patent or copyright ownership interests. Vendors, for their part, may also be ignorant or misinformed about IP rights. Anyone hiring a vendor should not assume that the vendor understands potential IP issues or that the vendor’s standard agreement (sometimes called a master services agreement) will adequately or satisfactorily address and allocate IP ownership.

| Type of IP | Default Owner (Subject to Exceptions) |

|---|---|

| Patents | Inventor(s) |

| Copyrights | Author(s) |

| Trademarks | User of mark (to designate source) |

| Trade Secrets | Rightful owner |

Seeking to obtain IP rights from a vendor after the end of the relationship can be difficult. You may find yourself without leverage to insist upon vendor cooperation or the vendor may no longer exist (or be deceased). And vendors may opportunistically seek windfalls to assign over IP rights after-the-fact. In worst-case scenarios, the vendor may own the IP and be able to freely commercialize it to your disadvantage, as well as to potentially block further independent development by you.

From the vendor’s perspective, an assignment of IP rights might be undesirable. But this is a question of leverage (bargaining power) and whether the vendor is willing and able to turn down potential new work. Though a suitable compromise may be to provide a license-back to a vendor, allowing certain uses by the vendor while still transferring IP ownership to the vendor’s client. An example is a portfolio license allowing the vendor to show examples of past work to potential clients. What makes sense in any particular situation will vary, of course.

Patents and Copyrights

For patents and copyrights, the general rule in the United States is that whoever creates the IP is the owner. In the absence of a written agreement to the contrary, this means that a vendor will generally own any patent rights or copyrights stemming from the vendor’s own efforts by default, even if the customer paid the vendor for it. But there are exceptions. And it is possible to agree in advance who will own the IP — that generally needs to be in writing.

“For patents and copyrights, the general rule in the United States is that whoever creates the IP is the owner.”

By statute, transfer of ownership of patents (or a patentable invention) and copyrights must be in writing — though copyright law allows the copyright owner’s duly authorized agent to sign an assignment. Any written document, including purely electronic materials, could include or constitute an assignment if it shows intent to presently transfer ownership rights. The written document should use words like “assigns”, “hereby assigns”, “hereby conveys, transfers, and assigns”, etc. to create a present transfer of ownership. Oral assurances will not transfer ownership of an invention (patent) or copyright; although limited implied non-exclusive licenses or equitable rights (e.g., shop rights) might still arise without being in writing.

Agreements that constitute merely an obligation to assign — typically phrased in the future tense such as with “will own” or “shall assign” language — do not effectuate an assignment of IP. Rather, obligations to assign require later execution of a separate written assignment. But ambiguous language relating to possible future agreements (such as “shall be owned as agreed upon”) may not even create an obligation to assign.

Some jurisdictions have different default rules about IP ownership. At least one U.S. state, Nevada, may vest initial ownership of patent rights with the inventor’s employer rather than the inventor by statute. Under common law, a “hired to invent” doctrine may affect patent ownership too, in limited scenarios. Some other countries also have laws that place ownership of an invention in the hands of the employer rather than the inventor. Though sometimes these laws establish only an obligation to assign. It is important to consider the location of the vendor, the location(s) of the individuals involved, and the location(s) were relevant activities took place to determine which jurisdiction’s laws will apply.

Joint development may also result in joint ownership. If the vendor and your business collaborate to jointly develop IP, by default they are each the owner of an equal and undivided interest in the entire IP right(s). Under the patent laws, in the absence of an agreement, co-owners can each independently exploit the invention without an accounting to the other (though all co-owners must join a lawsuit to have standing to sue an accused infringer). Under copyright case law, an accounting is due to the other co-owner(s) for profits arising from the jointly-owned work to prevent unjust enrichment. Joint development agreements or the like can set forth various ownership rights in advance and can also govern the handling of relevant pre-existing “background” IP.

All the above concerns also apply to vendors themselves. For patents, an invention by a vendor’s employee is generally not automatically owned by the vendor. And if a vendor retains a subcontractor or non-employee then copyright ownership would likely initially vest in the subcontractor/non-employee creating a given work in the absence of an assignment or valid work made for hire agreement. Therefore, in the absence of a warranty relating to the vendor’s ownership of IP and/or a no-subcontracting contractual provision, or intimate knowledge of the circumstances involved in the creation of the IP, there is no assurance that an assignment from the vendor (alone) will transfer all IP ownership to you.

“Work Made for Hire”

An important potential exception to initial ownership under U.S. copyright law involves oft-misunderstood “work made for hire” statutory provisions. There are two, and only two, ways to qualify something as a work made for hire under current law. First, a copyrightable work prepared by an employee within the scope of his or her employment is deemed authored by and thus automatically owned from the outset by the employer. But vendors and even “internal” independent contractors do not fall within that definition.

Second, parties without an employee/employer relationship can also agree in writing that a work will be a “work made for hire” but only for nine categories of uses of works enumerated in 17 U.S.C. § 101, which may not apply—parties cannot contractually expand those statutory categories.

A “work made for hire” is-

(1) a work prepared by an employee within the scope of his or her employment; or

(2) a work specially ordered or commissioned for use [i] as a contribution to a collective work, [ii] as a part of a motion picture or other audiovisual work, [iii] as a translation, [iv] as a supplementary work [see definition below], [v] as a compilation, [vi] as an instructional text, [vii] as a test, [viii] as answer material for a test, or [ix] as an atlas, if the parties expressly agree in a written instrument signed by them that the work shall be considered a work made for hire. For the purpose of the foregoing sentence, a “supplementary work” is a work prepared for publication as a secondary adjunct to a work by another author for the purpose of introducing, concluding, illustrating, explaining, revising, commenting upon, or assisting in the use of the other work, such as forewords, afterwords, pictorial illustrations, maps, charts, tables, editorial notes, musical arrangements, answer material for tests, bibliographies, appendixes, and indexes, and an “instructional text” is a literary, pictorial, or graphic work prepared for publication and with the purpose of use in systematic instructional activities.

Definition of copyright “work made for hire” from 17 U.S.C. § 101

The “work made for hire” doctrine is frequently misunderstood. In practice, it might even be single the most misapplied and confusing provision in all IP law. Simply because you pay someone to make or provide something copyrightable is not enough. And even having a contract that purports to establish something a work made for hire may not actually achieve that goal. It is fairly common for contracts to include language about work made for hire that does not apply and has no legal effect. Only things that meet the statutory definition of “work made for hire” are legally effective.

Because the statute defines categories of possible works made for hire by a somewhat arbitrary and limited list, which is based on “use” rather than the inherent characteristics of the work, it may be difficult to know upfront if something will qualify with certainty. For instance, if a vendor is specially commissioned to write some text, that text could qualify as a work made for hire if commissioned for use as an “instructional text” but the identical text would not if instead commissioned for use in a novel or on an advertising billboard. Moreover, whether vendor-created software source code qualifies as “a contribution to a collective work” and/or “a compilation”, and was intended to be used in that manner, may be far from clear, particularly before any work begins. And agreements, on their face, may not clarify these crucial facts.

A work made for hire not only affects who owns the work but also who is considered the author. This can potentially be significant for copyright termination rights. The persons(s) who actually prepare a work made for hire have no termination rights, whereas person(s) who assign rights to a work can potentially invoke terminate prior assignment transfers (or licenses) decades later.

For older works, created before the 1976 Copyright Act, a much different “instance and expense” test was applied to determine who is the copyright owner. Under that older test, which is inapplicable to recently-created works but can still apply to old works, the commissioning or hiring party may be treated as an “employer” and thus the “author” and copyright owner for things a vendor or outside contractor creates—regardless of the type of intended use of the work.

Trade Secrets

The rightful owner of trade secret rights will be the party that develops the trade secret information, by default. This means technical know-how, etc. developed independently by a vendor will normally belong to the vendor. It may be unclear whether relevant trade secrets were part of “background” IP that pre-dated a relationship with the vendor or not, which can potentially become a point of dispute later on. But a written agreement can be used to establish intended trade secret ownership from the outset.

On the other hand, confidential information developed by a vendor might lose trade secret status if shared with a client business (or others) without reasonable measures to maintain secrecy. This might limit or prevent a vendor from attempting to assert trade secret rights against its client and/or its client’s customers, particularly if there was no non-disclosure agreement (NDA) or other enforceable contract term.

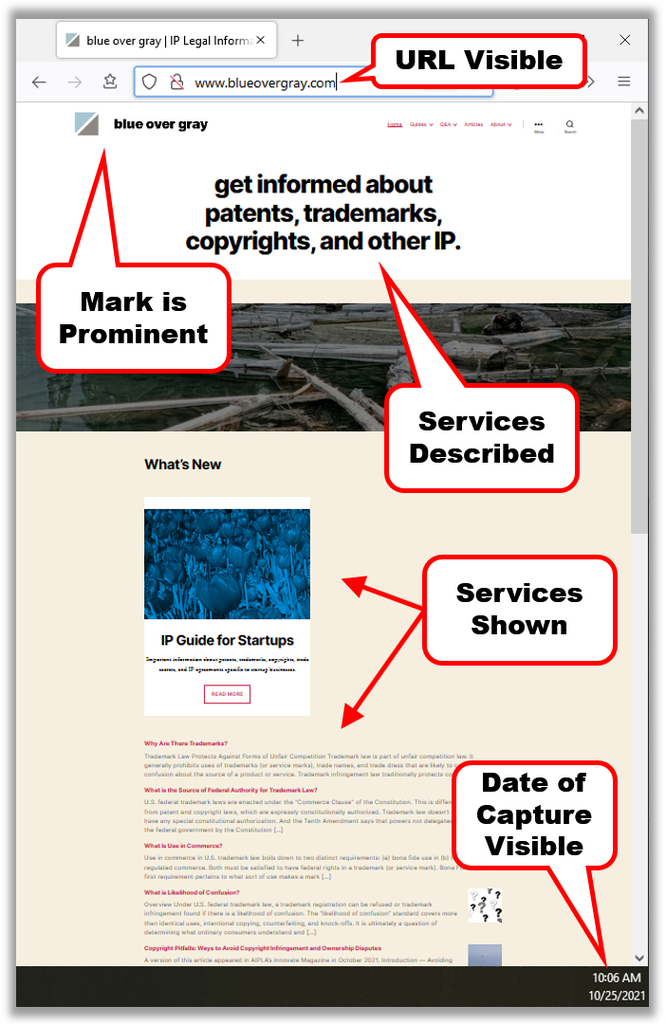

Trademarks

U.S. trademark rights accrue to the party actually using a mark in connection with commercial activity to designate the source of goods and/or services. For instance, a marketing firm creating a brand strategy and identifying a proposed mark for a client would not obtain U.S. trademark rights because only the client business would use (or intend to use) the resultant mark in commerce. But many other countries have first-to-register systems, which might allow a vendor to register your mark. Ownership of non-trademark rights, such as copyright, in graphical logos intended to be used as trademarks might be a little more complicated and might raise other issues too, including a potential divergence in who owns the copyright and trademark rights.

Austen Zuege is an attorney at law and registered U.S. patent attorney in Minneapolis whose practice encompasses patents, trademarks, copyrights, domain name cybersquatting, IP agreements and licensing, freedom-to-operate studies, client counseling, and IP litigation. If you have patent, trademark, or other IP issues, he can help.