People unfamiliar with patents and patent law are often confused about published patent applications. This article provides a brief overview of what a published patent application is and, importantly, how it differs from a granted patent.

Contents of a Published Application

Pre-grant publication means that patent applications that have not yet been fully examined are published while still pending. This gives the general public a view of the contents of the pending application. And even if no patent is ever granted, the contents of the published application are normally still made public (with some exceptions). Published patent applications can be relied upon as prior art against later applications. In the USA, only non-provisional utility and plant patent applications are subject to pre-grant publication. Pre-grant publication normally occurs after eighteen months have elapsed from the earliest priority date.

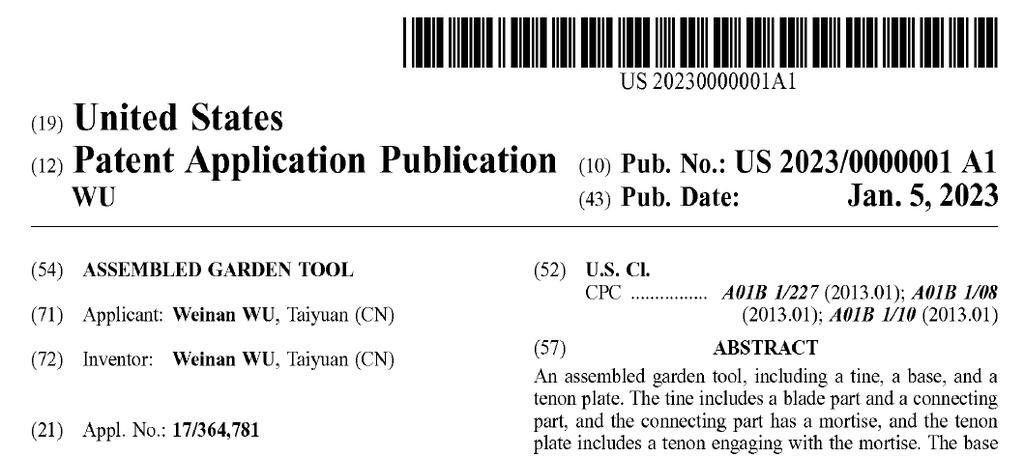

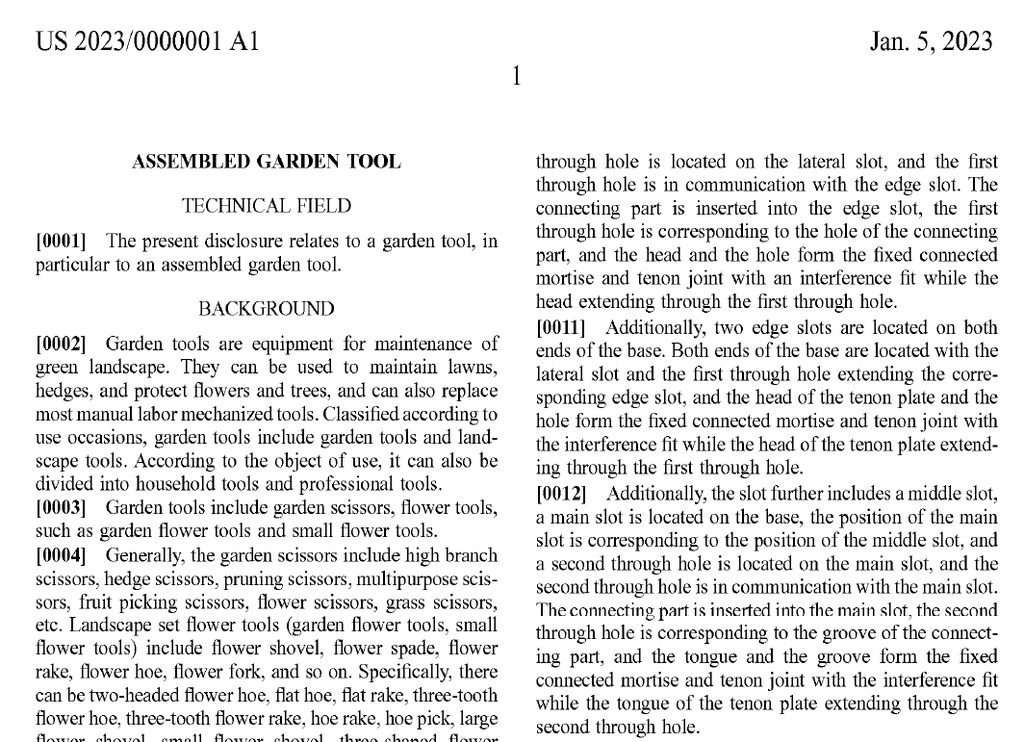

A published patent application—or patent application publication—will take a form determined the relevant jurisdiction. In the USA, for example, each application is specially formatted for pre-grant publication in a two-column format using paragraph numbers. This means the appearance of the published application will differ from what the applicant(s) originally filed.

The published application might also include amendments, such as amendments to the claims or drawings. In some uncommon instances, amendments might be published that are later disallowed and omitted from a subsequent granted patent. But amendments submitted too late for inclusion might not be included with the publication. And appendices included in patent applications are generally not published. The USPTO can refuse to publish certain information prohibited by law or that is offensive or disparaging. Additionally, as a consequence of official preparations and formatting efforts for publication, there can sometimes be discrepancies and printing errors, in which the published version unintentionally differs from the applicant’s original application.

In some other jurisdictions, such a PCT application publications, published applications merely take copies of the application as filed by the applicant and add a cover sheet. In other words, the application is not reformatted and reflects what the applicant submitted.

Publication Numbers

Each patent application publication is assigned an official publication number. In the USA, and with PCT matters, the publication number differs from the application serial number assigned upon filing by the relevant patent office. Although in some jurisdictions the publication number may be the same or nearly the same as an application serial number.

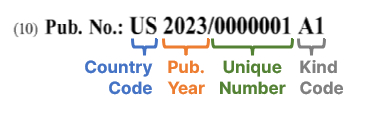

The anatomy of a publication number in the USA is shown as follows:

There is a four-digit year followed by a slash followed by a seven-digit number unique to each published application, and the concluded with a kind code. The unique-seven digit numbers are sequentially assigned to each newly published application. The kind code indicates the type of publication, with “A” generally indicating a published application and “B” generally indicating a granted patent. A two-letter country-code prefix to patent publication numbers can also be present, or appended, to indicate the jurisdiction of the patent publication.

Be aware that some patent searching databases use confusing variations on official patent publication numbers and kind codes. For instance, the Espacenet portal from the European patent Office (EPO) truncates U.S. published application numbers and shortens the unique seven-digit number to a six-digit number (but dropping a leading zero). Also, some databases will retroactively apply an “A” kind code to old granted U.S. patents, from before the USPTO began printing kind codes on patents or making pre-grant publications at all.

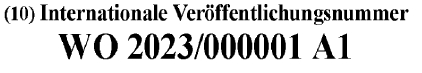

Each jurisdiction has a slightly different format for publication numbers. For instance, PCT publication numbers have a “WO” country-code prefix and use a six-digit unique identification number.

Publication Makes File Wrapper Available Too

Before publication, the substantive contents of pending patent applications are kept confidential by the U.S. Patent & Trademark Office (USPTO). But upon publication, which normally happens after eighteen months from the earliest priority date, the file wrapper of a published patent application is also made public by the USPTO. This allows the public to monitor the status and ongoing prosecution history of the corresponding application. While the “published application” is a discrete, stand-alone document, its publication also makes other information publicly available too. But, strictly speaking, a published application refers only to the stand-alone published version of the application and not to other materials in a file wrapper made available to the public through other channels.

Differences From a Granted Patent

A published patent application is much different from a granted patent (also called an issued patent). This is often misunderstood. Although the differences between published applications and granted patents are very significant.

In all but a few countries, patent applications must undergo a substantive pre-grant examination that establishes patentability before a patent is granted. A pre-grant patent publication merely indicates that the applicant(s) are seeking—or previously sought—a patent. But there are no enforceable patent rights unless and until a patent is granted. The existence of a published application for an application that is still pending simply means that a patent might be granted. Plus, the scope of the claims in any later-granted patent may differ from those in the published application. By way of analogy, just because someone files a lawsuit does not mean that he or she will win the case or that all the allegations are all true.

A common mistake is to refer to a published patent application as a patent. But they are not patents! It is reasonable to call them patent documents, or patent-related documents. But a published application is not directly enforceable by itself. Only a granted patent can be enforced. This is the most important distinction. A published patent application does not present immediate and direct infringement risks like a granted patent. Although the technical teachings and disclosures in a published patent application may still be prior art against later patent application claims. Yet a published application and a later related patent are often merely cumulative, meaning (apart from different publication dates) they are redundant in terms of their substantive teachings.

Another potentially confusing aspect of published patent applications is that you cannot understand the current status of the underlying patent application from the published patent application alone. A given published application may have matured into a granted patent since publication, or might have been abandoned (and/or another related “child” application might have been filed too). It is necessary to look up the current status in official records, such as though the USPTO’s Patent Center portal. Most paywalled, proprietary patent searching databases provide at least some status information, and a few (but definitely not all) free, open-access patent searching databases provide some status information. But finding and interpreting current status information is not always straightforward.

Austen Zuege is an attorney at law and registered U.S. patent attorney in Minneapolis whose practice encompasses patents, trademarks, copyrights, domain name cybersquatting, IP agreements and licensing, freedom-to-operate studies, client counseling, and IP litigation. If you have patent, trademark, or other IP issues, he can help.